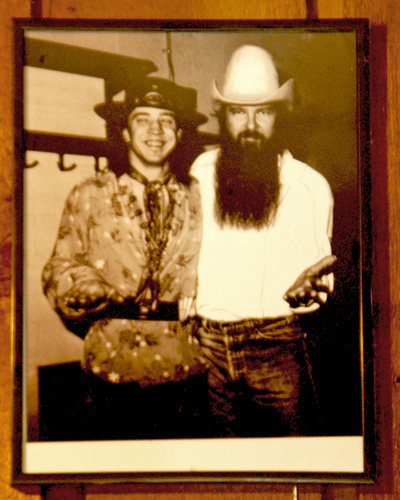

Stevie Ray Vaughan with fellow Texas Legend Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top. (photo credit James Cubed Design via Flickr)

Stevie Ray Vaughan – even the name sounds legendary, huh? SRV was a part of the later period of the “Blues Revival” that initially started in the 1960s. The demand for authentic blues music in the 1970s and ’80s opened the door for Stevie and his rude brand of the blues to take the Austin music scene by storm. He’s been a household name in electric guitar ever since, and it’s no wonder why: he had enough soul and tenacity on the guitar to satisfy any avid blues lover. Even today, almost no one has truly filled his shoes.

Stevie had attitude and a deep desire to follow his roots, but owned a sound unlike anyone that came before him. His guitar tone was dynamic and full of feel and phrasing, his voice powerful and sincere. He was downright unstoppable. Sadly though, on August 27, 1990 Stevie’s time in the spotlight ended due to a tragic helicopter crash; hIs career lasted for less than a decade. Despite this, Stevie managed to change the blues world forever with a career that truly was the stuff of legend.

SRV’s story started sometime around 1963 when he was just a young kid. He lived with his guitar playing older brother, Jimmie Vaughan, who also was destined to become a successful blues musician in his own right. Jimmie played a crucial role in showing Stevie the blues and introducing him to the guitar. In a 1984 Guitar World interview, SRV was quoted as saying:

“Jimmie would leave his guitars around the house and tell me not to touch ’em. And that’s basically how I got started. I actually wanted to be a drummer, but I didn’t have any drums. So I just got into what was available to me at the time.”

As little Stevie took an even bigger interest in the guitar, Jimmie gave him a few hand-me-downs. He was downright marinating himself in the blues then, acquiring several Lonnie Mack records and copying his licks himself. HIs brother Jimmie would bring his own records home, too and introduced Stevie to countless bluesmen of the time like Albert Collins, B.B. King, Buddy Guy, Hubert Sumlin, and Albert King, his biggest musical influence. A love affair with the electric guitar had taken root.

Years later, Stevie found himself playing guitar in a band called Blackbird, and shortly after that joined a band called The Chantones with future Double Trouble bassist Tommy Shannon. He then eventually procured a Stratocaster, likely because of his fascination with none other than Jimi Hendrix. At this point, his brother Jimmie had moved to Austin to follow the wave of public support for the blues, especially originals, which were largely missing from the Dallas scene they lived in. In 1972, Stevie dropped out of high school and decided to try his luck moving to Austin to play the blues. He quickly rose through the Austin scene, lovingly becoming known as “Little Stevie Vaughan.”

Stevie continued to make a name for himself as a fantastic soloist, as well as a gifted singer, and played in several bands around town. In 1977 SRV left his band at the time, The Cobras, to form Triple Threat Revue. Unfortunately, due to clashing egos, the band dismantled and was pared down to a trio which then became Double Trouble, comprised of Tommy Shannon on bass and Chris Layton on drums. This would be the vehicle for Stevie’s most popular music and his career’s most associated touring act. This power trio lineup gigged around Austin’s club scene for several years, gaining popularity along the way.

The Big Break

As fate would have it, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble landed the opportunity to perform at the 1982 Montreaux Jazz Festival where they impressed none other than superstar David Bowie. He approached SRV afterwards and asked if he would appear on his next album Let’s Dance, and have his band Double Trouble accompany him as the opening act for the world tour. SRV took the opportunity to play guitar on Bowie’s album, but due to disputes over the details of the press for the world tour, he declined to join on for it. This ultimately earned him a great deal of respect on the Austin blues scene for sticking to his roots.

Interestingly, that same performance at the 1982 Montreaux Jazz Festival caught the attention of Jackson Browne as well, and Browne later offered the band three days of free recording time at his own recording studio in Los Angeles. According to the engineer Richard Mullen, the first day of recording was spent setting up gear, and that the actual recording was done in only two hours with no overdubs. They treated it just like a gig, and ran down their live set, took a short break, and played the whole set again, choosing the better of the two takes for each of the tracks on the album. Whoa. Producer John H. Hammond later picked up the demo and signed them to Epic Records.

Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble then decided to release their demo as their first major label debut. On June 13, 1983 their demo became the classic Texas Flood album. Many of the tracks from this seminal album would become fan favorites and staples of his live sets, including “Texas Flood” (a cover of a 1958 song by blues singer Larry Davis), “Love Struck Baby” (a hit single that garnered tons of MTV airtime), and the classic “Pride and Joy.” Texas Flood eventually made it to double platinum certification. Not bad for a debut album.

The Gear

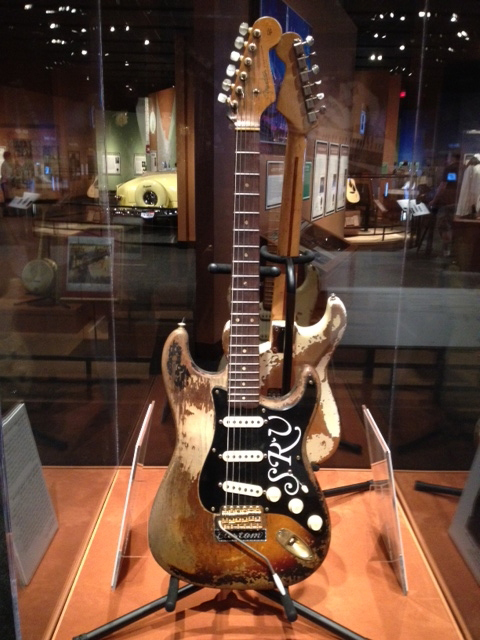

Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “#1 Strat”

SRV was known for a couple key pieces of gear, namely Fender Stratocasters and amps from Fender and Marshall. However, he used several other amps and effects to achieve his classic tone. Take for instance his V846 Vox Wah that was actually owned by Jimi Hendrix. His older brother Jimmie allegedly acquired it from Hendrix when his own blues band shared a bill with them in Fort Worth, Texas. In his later period in 1988 he also starting adding in new effects to his rig like the Dallas-Arbiter Fuzz Face pedal to satisfy his obsession with getting Hendrix’s tone. He used this on his solos for “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” and “Couldn’t Stand the Weather.”

Fun Fact: Stevie had his tech Cesar Diaz modify the germanium transistors in his Fuzz Face pedal to be able to withstand outdoor gigs and stage light interference. Interestingly, he regularly used a Marshall Major Lead head rated at 200 watts for his super clean tones, but it was susceptible to voltage spikes and tube failure. If the amp made it through his set, he would use it as his main amp for his cover of “Voodoo Child” in ode to Hendrix.

An Ibanez TS-808 Tube Screamer that is claimed to have belonged to Stevie Ray Vaughan.

There are plenty of examples of alternate guitars and amps that Stevie dabbled with, but he eventually settled on a few staple pieces of gear. On Texas Flood for instance, he used several 1964 blackface Fender Vibroverb amplifiers, as well as a few Dumble Steel String Singer heads with Dumble 4×12 cabinets. His tone for that album was a blend of both the Fender and Dumble amplifiers together and not specifically one or the other. The exact amp blend depended on which combination of amps sounded best for each song. He was also reported to have only used an Ibanez Tube Screamer for the album’s effects. Amps were almost always close-mic’d within a few inches of the speaker cone with little to no room miking. Instead, the engineers relied on post-production effects to achieve the room sounds they wanted.

Our trusty gear for this video included the Fender SRV Strat and a Deluxe Reverb amp.

The Video

Because our video was a note-for-note replica of Stevie’s song “Pride and Joy,” we wanted to see how we could imitate his huge tone with minimal gear, and ideally the kind of gear a guitarist of average means could acquire. This proved to be a bit tricky — the ’64 Vibroverb amps Stevie used have become highly collectable, not only because of his career, but because fewer than 600 of those amps were reported to have been made. Prices for these amps today can reach well above $10-20k. The search continued.

We made sure to use a Fender Stratocaster in our video because it was arguably the largest component of Stevie’s sound. We used an obvious choice: the Fender Stevie Ray Vaughan Stratocaster that is based on his classic “Number One” Strat. That legendary guitar was a 1963 Fender body with a 1962 Fender D-shaped neck.

Fun Fact: The fretboard radius started out as a more rounded 7.25” but ended up flattening out to about a 9” or 10” radius due to extreme usage.

With the Strat down, we kept things as simple as possible and fed our signal into an Ibanez TS-9 for one solo, and an Ibanez TS-808 for the other to demonstrate each Tube Screamer’s tonal profile. Stevie would use his pedal as a clean boost, maxing out the Level control and turning the Drive control almost all of the way down.

Fun Fact: Stevie was reported to have favored the TS-808 variety of the pedal, but as it turns out, most concert photos and other live tour footage seem to indicate that he likely only used the TS-808 for the early part of 1982 until Ibanez released the TS-9 version of the pedal later that year. There is no evidence he went back to the TS-808 after this point. Interestingly, Stevie also used the TS-10 version of the pedal for generating feedback and higher gain distortion sounds that weren’t possible with his amps alone.

We used both an Ibanez TS-808 and TS-9 Tube Screamer in different sections of the video.

Circling back to our amp dilemma, we opted for a more common blackface Fender amp, the Deluxe Reverb. The amp is low-wattage enough that we could push it into the break up point at more comfortable volumes. With the Tube Screamers then set as a clean boost, we pushed the front end of the amp and generated much more gain while retaining dynamics and tone. That being said, we were aware that the amp of choice for Stevie was usually either a Fender Vibroverb amp, or its larger cousin the Fender Super Reverb. However, Stevie only preferred those much larger and higher wattage amps to satisfy his need for minimal distortion tone at higher gigging volumes. Ultimately, the Deluxe Reverb provided the tone we needed for our video, and did so at lower volumes. Using nothing but these few simple pieces of gear, we were able to access a great sounding SRV tone. Check out the video linked at the top of this page to see how it turned out.

There is just one last piece of the puzzle to play like SRV though, and it’s a big one.

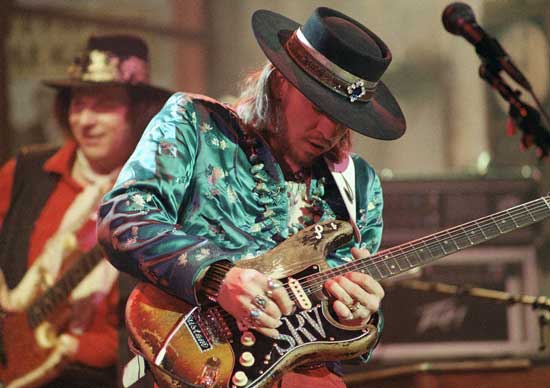

The Technique

Stevie’s technique was second to none. It’s been said that he had extraordinary grip strength in his hands that allowed him to more easily accomplish his forceful playing. Stevie loved to really strike his strings exceptionally hard with his picking hand. The same goes for his left hand – he would grip the neck so hard that he routinely swapped out his stock Fender frets for much larger ones — he reportedly even used bass frets — so they could take the abuse of his bends and vibrato. Pictures of his salvaged gear show his equipment absolutely trashed.

Stevie Ray Vaughan performing on his #1 Strat

Stevie also had a proclivity for using gigantic guitar strings, usually GHS brand, ranging from .013-.058 gauge to as high as .018-.074 gauge. Sheesh! He always tuned his guitar one half step down. He played with a heavy right hand, and if you listen to his albums, you can certainly hear how powerful the combination of his picking attack, giant strings, and cranked amps was. Try this at home if you have a tube amp: turn your volume to a lower setting and pick with a soft attack. Now turn your amp up and continue to pick quietly. You’ll notice the tone thickens up a bit when the amp is running louder. Now give the strings a much stronger picking attack and hear how much extra lows (and highs too) you’ll hear in the tone when the amp is getting worked harder. You can’t quite get the full Stevie tone unless you run your amps loud and “dig in” to the strings a bit more than the norm. Practice this while still maintaining relaxation in your arms to avoid any strain.

Next up is working on your vibrato skills. As I mentioned earlier, Stevie had very strong hands, and you’ll notice that his vibrato is generally wide and aggressive because of it. Practice maintaining vibrato that is firm, yet even for best tonal results. Working with a metronome to maintain the vibrato speed evenly is a good idea as well. Don’t be afraid to go a little crazy though – this stylistic effect was a trademark of SRV’s sound. Once you are feeling confident with your vibrato, practice on your bends next.

This section is similar to our last installment of Legends of Tone that featured David Gilmour. Gilmour was very well known for his bends, just like SRV. The main difference is that SRV’s bends were much more intense. They were the stuff of legend: wailing, yet exactly appropriate for his music. Check out last month’s Gilmour post for a few quick tips on executing clean bends, then work on adding that extra vibrato. Be warned though – when it comes to good bends (especially with wide vibrato), the devil is in the details. Be patient if you don’t have experience with this already. Just remember, intensity of sound seems to be the consistent characteristic to nailing SRV’s style. Keep your bends fierce, your vibrato wide, and your amp loud.

Gone Too Soon

Following a concert supporting Eric Clapton at Alpine Valley on August 27th, 1990, Stevie Ray Vaughan was about to board a late night helicopter flight to Chicago amid dense fog conditions. He had initially been notified by his tour manager that a helicopter was booked for himself, his brother Jimmie and his wife Connie. Unfortunately, by the time they arrived at the helicopter it was already occupied by Clapton’s agent Bobby Brooks, bodyguard Nigel Browne, and assistant tour manager Colin Smythe. In a rush, Vaughan asked Jimmie and Connie if he could grab the last seat on this helicopter. They agreed and took a flight later that night.

A statue of Stevie Ray Vaughan stands in Austin, TX. (Photo credit: sbmeaper1.jpg via Flickr)

Less than a mile away from the takeoff point, the pilot was unable to see an approaching large ski hill obscured by the fog. The helicopter crashed, killing all four passengers and the pilot instantly. Eerily, a day before, Stevie had told his band and road crew that he had a horrific nightmare in which he witnessed his own funeral surrounded by thousands of mourners. He felt “terrified, yet almost peaceful.” A few days later on August 30th, this premonition became a reality when over 1,500 people attended his funeral service in Dallas with more than 3,000 others waiting outside. Several close friends and musicians gathered in mourning, including Eric Clapton, Jackson Browne, Buddy Guy, Stevie Wonder and many others.

Though SRV left the world in a most devastating way, he left us with a catalogue of music that remains a 20th century watershed of blues music. It seems unfair to say that Stevie was simply a stellar blues guitarist – he was a stellar musician through and through. He rightfully deserves his cemented legacy and a large feature here on our Legends of Tone blog series. At the very least, I hope that this piques your curiosity for all things Stevie Ray and inspires your own exploration into his life and work as a supremely gifted bluesman.