The president of Gibson during its most accomplished era, the man who oversaw the development of the Les Paul and first conceptualized the ES-335, nearly took a job with Brach’s Candy.

Perhaps in a parallel universe, Ted McCarty does take up a position at Brach’s and we all enjoy some wondrous confections that not only taste divine, but change the candy industry for decades to come. We’ll never know, but I think musicians much prefer the way things turned out in this universe.

The Road to Kalamazoo

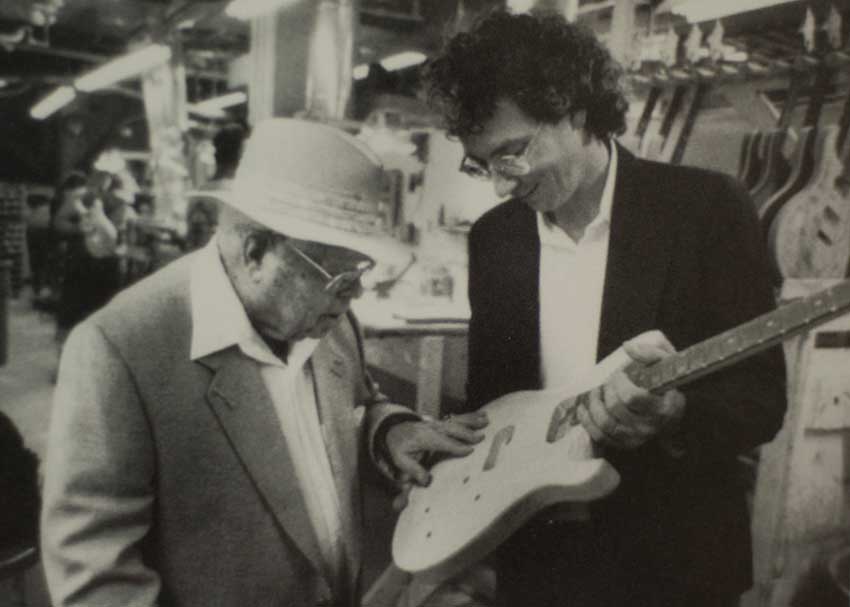

Ted McCarty (photo courtesy of PRS)

Following his graduation from the University of Cincinnati’s School of Engineering in 1933, Ted McCarty (who was not a musician himself) entered the music world with a job overseeing Wurlitzer’s real estate affairs in retail stores and manufacturing. After 12 years at Wurlitzer, however, McCarty sought a new path.

Other executives had ideas that McCarty’s path would lead him to their companies. Brach’s sought McCarty to fill the role of assistant treasurer, and talks between them were taking shape. However, M.H. Berlin, then-CEO of Gibson, thought McCarty would be a perfect fit for the guitar company. This notion, by the way, came to Berlin via Bill Gretsch, who recommended McCarty after having lunch with him.

Berlin knew McCarty was considering the job at Brach’s, but asked him to check out Gibson’s Kalamazoo, MI headquarters and give a report on his thoughts on the business. McCarty did so, and soon after was offered a general manager position from Berlin. McCarty was hesitant to move his family to Michigan, but after some persistent negotiation from Berlin, McCarty agreed and joined Gibson in 1948. Two years later, company president Guy Hart was asked to resign and McCarty took his role. Gibson’s golden age was underway.

Gibson’s “Golden Age”

In some ways, it’s odd that non-musicians have been the source of so much innovation in musical instruments. On the other hand, it makes a lot of sense. McCarty and other figures like Leo Fender were able to design and consult from a perched perspective, one that wasn’t influenced by musical biases or personal preference.

In 1949, the year after McCarty came on board, Gibson introduced the ES-5. Marketed as an amplified version of the L-5 acoustic, the ES-5 delivered on McCarty’s mission to expand the company’s selection of electric guitars. This hollowbody archtop introduced more tonal options for guitarists than ever via its three-pickup layout. Guitarists could adjust individual volume knobs for all three pickups along with a master tone knob to get their desired blend.

That same year, McCarty developed a pickguard of his own. McCarty believed traditional pickups of the time stifled the natural vibration of a guitar’s top — his design mounted a pickup to the guitar’s pickguard, leaving it clear of the top. Volume and tone knobs also were mounted to the pickguard, and an output jack was included. Though it was made standard on Gibson L-7 guitars for a time, the “McCarty pickguard” worked well as an aftermarket piece, as it was easy to install on an archtop, (even an acoustic one) came in two shapes for guitars with or without cutaways and included on-board volume and tone controls.

Another innovation of 1949 came in the ES-175, which introduced guitarists to the sharper curve of the Florentine cutaway. This dramatic swoop was favored by jazz artists who needed to reach way up on the frets, and it continued on as a favorite of fusion guitarist Pat Metheny. It could be argued that the ES-175 helped build a home for lead guitar on the upper reaches of the fretboard and helped shape guitar culture to come.

Gibson’s electric age was beginning to take shape. But as important as the developments of 1949 were, Gibson was just approaching the foothills of its greatest accomplishments.

The Les Paul

So much has already been written about what is perhaps the most famous guitar ever: The Gibson Les Paul. As this is a study of Ted McCarty, I’ll try to stick primarily to his contributions here. The year was 1952, and Gibson was looking to get into the solid-body guitar market Leo Fender created in 1950 with the Broadcaster. McCarty’s answer? Counter Fender’s weak points. Many critics (McCarty included) viewed the Broadcaster’s slab body and bolt-on neck as inferior. McCarty sought to craft a solid-body guitar worthy of the current state of amplification.

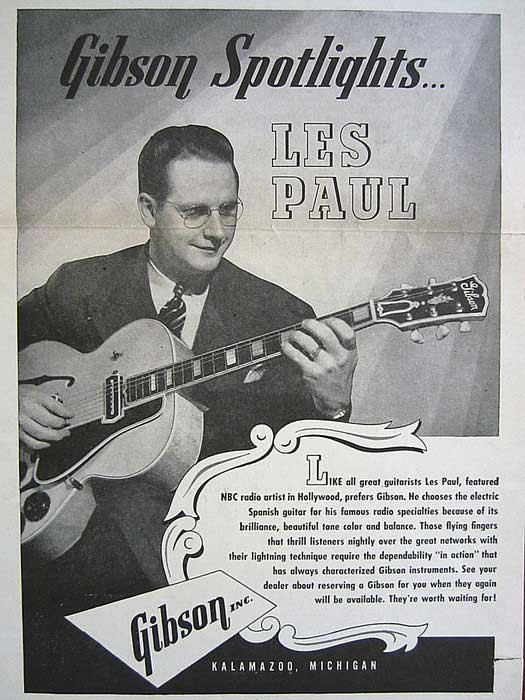

McCarty and Gibson designers developed a prototype of a then-unchristened solid-body guitar, but something was missing: an endorsee. According to McCarty, he suggested Les Paul for an endorsement, as he and Mary Ford were currently at the top of the charts. A visit to Delaware with the prototype in tow yielded two stamps of approval from Paul and Ford, and a five-year contract: Les Paul would only play Gibson guitars in public.

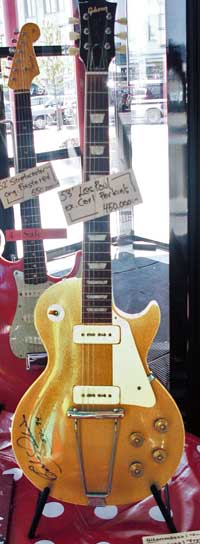

Gibson shipped out the original Les Paul in 1952, complete with luxurious golden finish, P-90 pickups and trapeze tailpiece. Today, the model remains a classic, but it wouldn’t reach its iconic status until a few tweaks were made. The first was the Tune-o-Matic bridge, developed in 1954 by McCarty. The individually adjustable string saddles made adjusting the action and intonation on Les Pauls and other guitars easier and more precise than ever. The Tune-o-Matic, paired with a stopbar tailpiece remains the standard setup on Les Pauls today and has been adopted by countless manufacturers over the years.

- A 1953 Gibson Les Paul for sale

- A 1958 Gibson Les Paul

The second breakthrough came via Seth Lover and would change the sound not only of the Les Paul, but music altogether. By wiring two single-coil pickups together and out-of-phase with each other, Lover was able to reverse the 60-cycle hum that plagued single-coil guitars like those made by Fender. The resulting pickup, known as the humbucker, yielded a fatter sound that would come to shape the voice of rock guitar. These “Patent Applied For,” or PAF humbucking pickups would make their first appearance on the Les Paul in 1957.

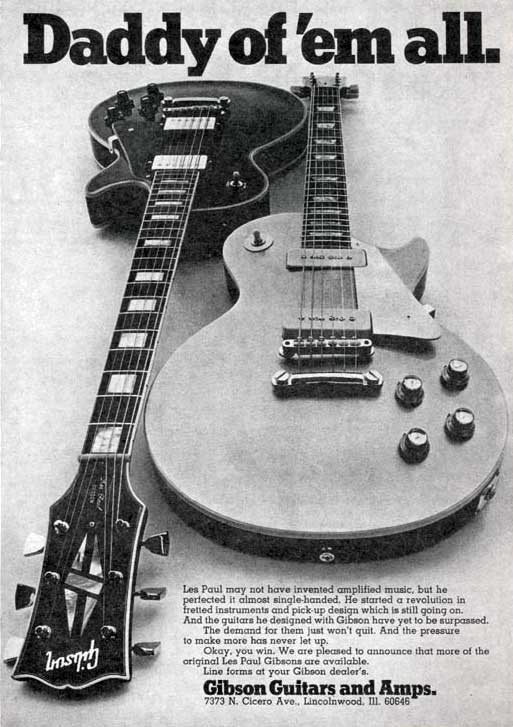

It’s worth noting that under McCarty’s leadership, Gibson would release several incarnations of the Les Paul: The student model Junior, the elegant Custom, the budget Special, the modest TV, and the Standard, which would introduce the sunburst finish. The decision to diversify the lineup and appeal to a wide variety of players at every stage helped Gibson to stay relevant for decades to come. Each of these models remain available in some form today and late ’50s Les Pauls with burst finishes are some of the most treasured guitars of all time.

Gibson Advertisements from the McCarty era

A New Middle Ground

Having gained experience now in solid and hollowbody guitars, McCarty would chart new territory in-between the two. Seeking a harmony between the feedback-resistant sound and sleek feel of solid-body guitars with the unrivaled warmth and resonance of hollow-body guitars, McCarty found a solution.

By marrying a solid maple center block with hollow sides made of laminated maple, he was able to craft a guitar that was almost as resistant to feedback as a solid body, yet could still be heard acoustically, and yielded unmistakeable, resonant tone when plugged in. The thinline body proved more comfortable than fully-hollow body guitars and the recently created PAF humbuckers were a perfect match tonally. The ES-335 was released in 1958 and found a home in the hands of players like Chuck Berry and Alvin Lee and even spawned personalized versions, like BB King’s Lucille. It would become known as McCarty’s proudest legacy.

Wave of the Future

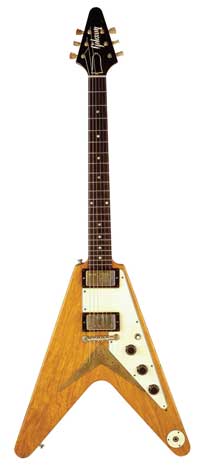

During the 1957 NAMM show, Gibson would showcase three new models that shocked some, awed others, and would become part of the company’s legacy and mythos for years to come. The Flying V, Explorer, and Moderne were like nothing guitarists had ever seen.

Fender was talking about how Gibson was a bunch of old fuddie-duddies, and when I heard that through the grapevine, I was a little peeved. So I said, ‘Let’s shake ’em up.’ I wanted to come up with some guitar shapes that were different from anything else.

Ted McCarty to Vintage Guitar Magazine, April 1999

The Flying V was the best received of the lot upon launch. The decision to use korina bodies in these futuristic guitars made them relatively light even given their large shapes. And let’s talk about that V shape, which so perfectly fit into the now retro-futuristic aesthetics of the late ’50s. Though a challenge to play sitting, the Flying V was comfortable to play standing up, and In the hands of players like Albert King and Jimi Hendrix, it gained popularity among rock and blues guitarists, and lives on today as an attitude-packed showstopper. In fact, you could say the need to play the V standing helped further push the idea of guitarists as rock stars in their own right who could draw in just as much attention as singers.

- 1958 Gibson Flying V

- 1958 Gibson Explorer

- Gibson Moderne (Heritage Edition re-issue)

Looking at the Gibson Explorer today, it’s apparent that the guitar was way ahead of its time. It didn’t fare as well as its V-shaped sibling upon its release, failing to capture a big following early on. But the Explorer would pay big dividends over time, and it could be the most influential of all the futuristic models. The model drew attention as harder styles of rock emerged in the mid 1970s, and manufacturers like Hamer (who developed a popular Explorer-style guitar) and Jackson (who employed Explorer-style headstocks on their guitars) owe a large debt to this model. The Explorer has aged well — its bold angles making it a favorite among metal heads since the late ’70s on through today.

The Moderne looks to be a sort of hybrid of the other two futuristic models, albeit with a unique headstock. Unlike the Explorer and Flying V it was not put into production; though Gibson did offer a limited run of them in 1982. The prototypes, of which McCarty said four or five were originally made, live on as the epitome of desired collectible guitars.

The Early ’60s

Gibson entered the new decade just as boldly as it exited the last. And though it may have made a few stumbles along the way, in typical McCarty era fashion, even the miscues of the time often reaped future rewards.

In 1961, Gibson issued a new Les Paul model, the Les Paul SG. And though it bore his name, this really wasn’t Les’ guitar at all. Designed without his consultation or input, the Les Paul featured a thinner mahogany body, slim mahogany neck, dual cutaways and humbucker pickups. Les Paul was displeased with the guitar and asked that his name be removed from its headstock. Gibson complied, but Les’ name wouldn’t be removed until 1963, when Les Paul’s contract with Gibson ended. From then on, the guitar was referred to as the SG (for “solid guitar”).

1962 Gibson Les Paul SG (Photo credit: Sellenman via Wikipedia)

While the SG may have upset Gibson’s chief artist endorsee, what Les disliked in the model, others appreciated. The SG would go on to become a favorite of Eric Clapton, Tony Iommi, Angus Young and several others, and players still appreciate it as the slimmest, most back-friendly Gibson solid-bodied guitar.

In 1963, McCarty would get radical again as he did with his futuristic models in 1958. This time, he hired car designer Ray Dietrich to create guitars based on hot rod cars. The Firebird guitar and Thunderbird bass were the results.

Though both largely borrow from the Explorer’s body shape, they each have important distinctions of their own. The two models were the first solidbody Gibsons to utilize neck-through construction, in which its neck ran through the body and featured wings attached. The Firebird made expert use of mini-humbucker pickups that gave it a distinctive tone still sought after today, along with unique “banjo” tuners adjustable from the back of the headstock. The Thunderbird was a direct challenge to Fender, which was dominating the electric bass market. It would find a foothold in harder rock styles and in the hands of players as diverse as John Entwistle, Nikki Sixx and Kim Gordon, among many others. Both models remain available today.

End of an Era

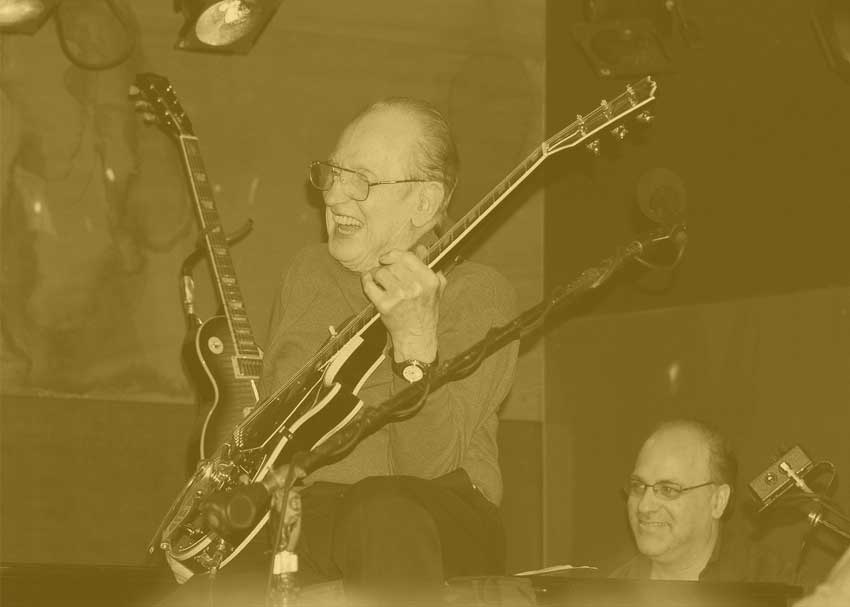

McCarty would leave Gibson in 1966 and go on to purchase and work for Bigsby, makers of the famed tremolo systems. He remained there for 20 years, and though his accomplishments at Bigsby are not as widely recognized as those with Gibson, it’s safe to say he helped steer the company through a time when the styles of music associated with Bigsby tremolos were waning in popularity. McCarty also helped keep Bigsby a household name despite increased competition from the likes of Floyd Rose and Kahler.

During his time at Gibson, McCarty consulted Paul Bigsby on his famous tremolo design. McCarty loved it, but had one gripe: the fixed handle was always in the way of a guitarist’s strumming hand. McCarty designed a new version with an arm that could sway and therefore stay out of the way when not in use. At the time Gibson was a mass buyer of Bigsby, and the design belonged to McCarty, so other companies like Gretsch were barred from purchasing the sway arm Bigsby tremolos. McCarty worked out a deal with Bigsby to let other manufacturers use the sway arm on their guitars if Gibson could purchase the tremolos at a discount. The two formed a close bond, and in 1965, Paul Bigsby sold his company to Ted McCarty. McCarty stayed with Gibson until they could find a replacement for him.

Not long after McCarty’s departure, Gibson underwent major struggles, as ownership would transfer to Norlin in 1969, a company formed by the merger of Gibson’s parent company, Chicago Musical Instrument Company and Ecuadorian Brewery ECL. Gibson (and other American guitar manufacturers) would soon see increased competition from overseas manufacturers that offered lower-priced guitars that were often direct ripoffs.

Still, McCarty’s leadership left Gibson with strong assets. His shrewd moves to acquire Epiphone in the late ’50s brought a close rival into the fold and planted the seeds for a budget line to help Gibson compete with their overseas copies. During his tenure, McCarty ramped up Gibson’s workforce with 10 times as many workers as when he started and had increased sales by 1,000 percent. This and the company’s now widespread publicity in the hands of countless major artists would help it stay relevant.

Mentoring Paul Reed Smith

In 1986, a fresh-faced young luthier named Paul Reed Smith was just embarking on his journey into guitar manufacturing. He had a small team and a successful first showing at NAMM, but wanted to grow the business and sought guidance. He had nervously called Ted McCarty to see if he might be open to doing some consulting. By that time however, McCarty was legally blind, and travel was difficult. Smith agreed to meet him in Kalamazoo, however, and the trip would prove well worth the ticket.

During their meeting and through subsequent talks afterward, Smith and McCarty developed a bond, and Smith would receive a book’s worth of knowledge and history on guitar craft and the industry itself. From stories detailing the construction of hallowed late-’50s Les Pauls to anecdotes about McCarty’s time with other guitar industry figureheads, to management advice, the talks helped Smith step into his role as head of PRS and grow the business to what it has become today.

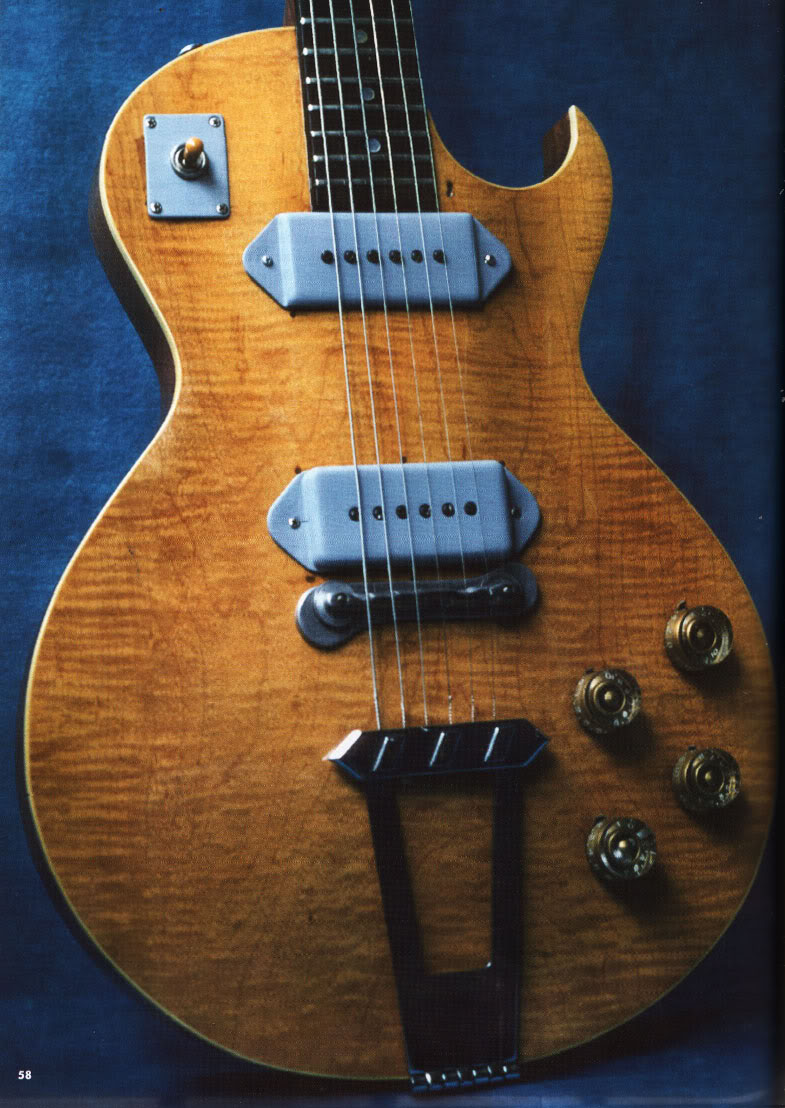

In 1994, PRS Guitars released the first McCarty model. Unique among their lineup, its features — like burst finish, covered humbuckers, and toggle switch, and thicker neck and body — evoked those of a late ’50s Les Paul. For Smith, the guitar was both a tribute to a legend and a gift to an old friend. Smith, who had discovered McCarty by seeing his name pop up time and again in Gibson patents, had now crafted a guitar to bear his name.

This year, PRS Guitars released the McCarty 594, a model with subtle changes. First is the slightly shorter 25.594″ scale length, from which the guitar gets its name. Other features make this a model that even more resemble a McCarty-era instrument: two volume and two tone controls, a Tune-o-Matic style bridge, and low-turn 58/15 pickups for warmer tone.

zZounds demo of the PRS McCarty 594 in late ’50s style

Impact on an Industry

Not only did Ted McCarty skillfully usher Gibson guitars into the electric age, he laid the foundation for what the industry looks like today. In many ways, things haven’t changed much since his heyday in Kalamazoo.

Gibson guitars produced during the “McCarty era” remain some of the most desired instruments on the vintage market. Their appeal is so great that Gibson (along with several other manufacturers) continue to build guitars today that feature the same specifications and as close to the same building practices as possible. His Tune-o-Matic bridge has remained largely unchanged and still serves as the standard on thousands of guitars today.

And for every one of McCarty’s home run ideas, there were many — like the Explorer and SG — that slipped at first, but would prove an indispensable hit years later. There’s no doubt Ted McCarty — who passed away in 2001 — belongs on the same tier as guitar innovators who came before and after him. Just as Fender emerged through its difficult CBS years thanks to the timeless quality of Leo Fender’s designs, Gibson would thrive after the Norlin years with much thanks to the innovations of McCarty.

Sources:

- NAMM | Oral History Series: Ted McCarty

- Vintage Guitar Magazine | Ted McCarty: I’m Not a Musician

- Walter Carter | The Gibson Electric Guitar Book: Seventy Years of Classic Guitars

- UC Magazine | Gibson Guitar legend Ted McCarty strums last chord

- VICE – The Creators Project | Instruments Of Change: The Forgotten Electric Guitar Hero Ted McCarty