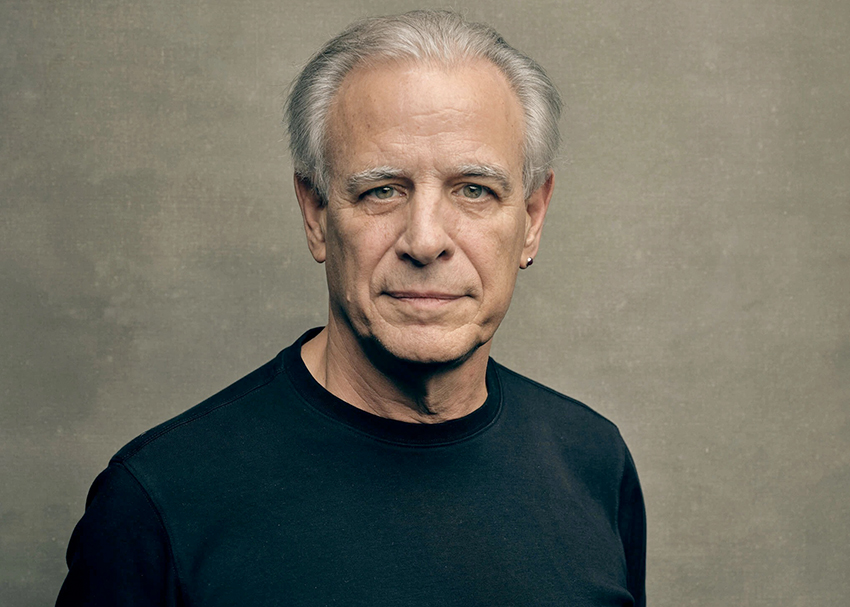

Had he followed the conventional audiologist’s path, Dr. Michael Santucci would still be treating musicians — but only after they’d experienced hearing loss, ear injury, and tinnitus. Instead, he entered the field with the mission to help working musicians protect their ears in order to prevent hearing loss and damage down the line.

The desire to help fellow musicians, an innovative spirit, and a few key encounters, led Santucci to develop his own musician-friendly earplugs, in-ear monitor systems, and hearing health clinic, all developed through his company Sensaphonics. To this day, he continues to innovate through the brand, as well as through ASI Audio, all while seeing hundreds of musicians at every level in his Chicago clinic.

Building a Better Earplug

Brought up in a musical family — his dad was a trumpet player in a big band, and his sisters are multi-instrumentalists — Santucci, a trumpet player himself, got to know and network with musicians in the Chicago music scene. In 1985, when a local band’s singer complained of tinnitus, Santucci wondered: why didn’t she just use those orange foam earplugs? After trying them out for himself, his first muddy listening experience made it all too clear: all the high-end detail was gone, and nothing came through but muffled low-end.

Those little foam earbuds did do one thing well — they provided a breakthrough moment. Musicians and performers needed hearing protection that didn’t eliminate the high-end of the frequency spectrum, and that more accurately matched the frequency response of the human ear.

In 1986, Santucci began his own research, visiting different recording studios to learn about what technology was out there for musicians and why hearing protection was failing to meet their needs. He met with Murray Allen, a legendary engineer and owner of Chicago’s Universal Recording Studios, to learn more. Murray had a real-time analyzer and Santucci devised a way to use it to test the frequency response of earplugs.

“I had these tiny little mics I put near my eardrum and we’d stick in foam and putty and all this stuff and take measurements with the speaker measured from the same distance with pink noise and we could look at the frequency response,” Santucci said.

The test gave empirical evidence to what Santucci had experienced on his own: these earplugs were gutting out the high-end of the spectrum, leaving little left but bass with no detail or clarity.

Related: How do Headphones Produce Bass Frequencies?

Learn about the science behind how diminutive drivers deliver full-sounding bass to your ears. | Read »

After this test, Santucci tried developing filters to correct this issue, but as he admits, he didn’t have the engineering background to do so. It just so happened that at that time, Mead Killion, founder of Etymotic research and a friend of Santucci, was developing an entirely new type of earplug, the ER-15. With a triple-flange design and a small filter, the ER-15 worked and fit completely differently than conventional earbuds of the time. Killion recruited Santucci to be his beta tester. He then gave one to Steve Rodby, bassist of Pat Metheny group and members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. They were a hit. From there, Santucci and Killion collaborated in developing Sensaphonics’ first in-ear monitor system.

Perfecting the In-Ear Monitor

It wasn’t long before Santucci saw more room for improvement. Most manufacturers of in-ear monitor systems were using round diaphragm drivers to pump sound into the ears. This design had one major flaw in regards to hearing health — since they sounded better when vented, they also let a lot more noise in.

It was during this time that Santucci developed the first in-ear monitors for musicians that used balanced armature drivers. The design was the perfect synergy of safety and sound: balanced armature drivers produce tighter bass the deeper they seal in the ear.

“Hearing loss prevention is what Sensaphonics represents — we want to have high quality audio or else nobody will wear it,” Santucci said. “But the main focus is not to see how many ears we can fill up with stuff; it’s to see how many ears we can save.”

This new design would be used by Ken Nordine, a famous Chicago jazz spoken word artist. For an upcoming local gig with the Grateful Dead, Nordine was planning to use another manufacturer’s wireless in-ear monitor system but found the cost prohibitive. As he would be performing seated, the wired Sensaphonics system was a viable option. The performance was a success, and Nordine let Santucci know that the Grateful Dead’s engineering team wanted some units of their own to record the next performance.

With inroads made with the Grateful Dead, Santucci went to Harry Witz, president of Chicago’s db Sound, which provided live sound rigs to the likes of major touring acts like The Rolling Stones, Metallica, Aerosmith, and others. Witz was impressed with Santucci’s in-ear monitor system, and agreed to work with him.

This partnership helped put Santucci and Sensaphonics on the map as the top choice for touring professional musicians needing in-ear monitors. But even with his company established as a leader in the field, Santucci still had plenty of work to do.

The Musician’s Clinic

As proud as he is of Sensaphonics and its progress in the world of in-ear monitoring, Santucci is even more passionate about hearing protection.

For the past 30 years, Santucci along with fellow audiologists and former students Dr. Heather Malyuk and Dr. Laura Sinnott have seen between 1500 – 2000 patients a year at the Musicians Hearing Clinic in Chicago. There, they conduct hearing tests, take ear impressions, and measure sound pressure levels (SPL) in paitents’ ears. Their efforts all go toward preventing hearing loss and treating the adverse affects of hearing injury, including tinnitus.

With a diverse client base ranging from local teenagers in bands to music teachers, symphony performers and A-list touring musicians, Santucci is literally in the ears of musicians at every level.

“I’ve got my my ear on the heart of what goes on with people’s hearing and their problems on stage because of hearing loss or because of hearing protection,” he said.

And the insights gleaned from talking to musician patients have led to some of Sensaphonics’ most impressive innovations. One recent development has enabled musicians to hear the stage and themselves in a whole new way.

Hearing in 3D

As patients told of how they would often pull out one of their in-ears to better hear the stage noise around them, Santucci grew troubled. The sudden spike in volume when removing an ear plug on a loud stage is especially dangerous. Plus, the perceived volume coming from just one in-ear monitor would be lower, so the performer would likely be turning their volume up to dangerous levels.

This was an area of both deep concern and opportunity. Musicians clearly needed in-ears that offered protection, while still granting them spatial recognition and awareness of what was going on around them.

“Like Steven Tyler said, ‘when I run to the front of the stage, Michael, and some woman says Steven I want your babies,’ I want to know which one said it!” Santucci said, quoting a famous client.

After some time researching, Santucci found a solution with ambient microphones that were EQ’d to match the frequency response curve of the human ear canal. To accomplish this sort of bio-mimicry, Sensaphonics engineers took measurements of over two dozen ear canal resonances, found the average, and tuned the mics to match it.

“So when you stick these isolating ear monitors in, you flip open the mic and it feels like you took them out…it sounds so natural,” Santucci said.

To take this concept even further, Sensaphonics partnered with Think-A-Move, a company based in Cleveland, OH, which specializes in military communication headsets. With Think-A-Move’s app development background, ASI Audio (a division of Sensaphonics) was able to create the 3DME active ambient in-ear monitors.

3DME is completely programmable — users can control everything from mix levels to gain, limiting, and parametric EQ. They can even save presets for use in different venues or with different bands. All of this is done via a smartphone app.

“I always say who’s your best sound engineer for you? You!” Santucci said.

Rethinking Volume

While everyone would be wise to care for their ears and take steps to protect their hearing, performing musicians are particularly at risk. Although many musicians think they are used to high volume, Santucci stresses the importance of re-thinking habits and beliefs about volume, especially as they return to practice and gigging after the COVID-19 lockdown.

Loudness is, as Santucci puts it, a “learned behavior” among musicians. As we come to develop and value a unique tone from our instrument, we seek that tone out no matter how loud we need to turn up to hear it. In studies, musicians consistently adjusted in-ear monitors to match the db output of what their amps or floor monitors were typically set to.

“I’m realizing that your brain has readjusted to lower levels because you’ve been away from loud sounds for so long,” he said. “And so our message is don’t try to get used to it again. Take advantage of this once-in-a-century opportunity to reset your levels and still feel all the emotion and joy and everything else without feeling like you’re compromising.”

It’s Never Too Late

One of the most common ailments people see Santucci in his clinic is not hearing loss, but tinnitus. Many mistakenly think that once tinnitus sets in, there is little point in trying to protect their ears any longer. Santucci stresses that this is not at all the case, and anyone at any age should continue to do everything they can to prevent further injury.

“It’s like sawing your finger half off; you’re talking to me so you have some hearing,” he says to patients. “Do you want to keep it or do you want to just keep sawing away until you have no finger left?”

The biggest threat to hearing, Santucci says, is personal listening systems. The risk of injury correlates not only with volume levels, but with the duration of time you expose your ears to high volume. And the choice of in-ear or over-ear headphones means little. Furthermore, when earbuds don’t firmly sit in the ear, users will turn up the volume to better block outside noise, which can make loose-fitting and over-ear headphones potentially more dangerous than well-sealed in-ears.

Since 2015, Santucci has worked with the World Health Organization, speaking on and advocating for safety measures for listening devices. As a member of the WHO’s Make Listening Safe initiative, Santucci has coordinated with academics, medical professionals, music device manufacturers, and venue operators to raise awareness of hearing safety and implement standards and guidelines for listeners.

While the cause of hearing protection still has a way to go in the music community, the industry has come a long way from its early days. Once laughed at during his first tradeshow appearance, Santucci’s idea of “ear plugs for musicians” no longer takes convincing. As younger generations of musicians adopt earplugs and invest in protecting their ears, older musicians are learning that earplugs no longer take the nuance out of music.

In the end, protecting our hearing will serve us all by keeping the music going for decades and decades to come.

The Dos and Don’ts of Hearing Health

- Do wear hearing protection

- Whether you’re at band practice, at a concert, or on the job, find a pair of proper earbuds to wear that will let you enjoy the music without the exposure to dangerously high volume

- Do limit your exposure to high volume sounds, especially for long periods of time

- Remember that hearing injury is the product of loud sounds and exposure time

- Do get a baseline examination and re-check hearing routinely

- Dr. Santucci recommends musicians test hearing once per year

- Do download a hearing health app

- Dr. Santucci recommends the NIOSH Sound Level Meter app

- Do keep up your cardiovascular health

- Your ears need proper blood flow to perform their best

- Don’t assume over-ear headphones are safer than earbuds or in-ear monitors

- The difference of a couple of centimeters distance from your eardrum doesn’t matter much

- Don’t take out one of your in-ears to better hear your surroundings

- The sudden rush of sound to your exposed earbud is dangerous, and

- You will likely turn up the volume to make up for the lack in perceived volume from the single monitor

- Don’t jump back into band practice post-lockdown at the same volume levels you were at over a year ago

- Try finding the same groove at a lower volume level — you will likely be surprised by the results!

- Don’t assume it’s too late to prevent further hearing loss!

Leave a Reply