Call them semiconductors, microprocessors, or integrated circuits, the silicon chips found in electronics of all kinds have been in short supply since mid-2020, with chipmakers struggling to meet unprecedented demand for the high-tech devices we use to work remotely, attend classes, stay in touch, and entertain ourselves at home in a global pandemic. Now, the worldwide chip shortage is affecting industries across the board. With chips a crucial component in everything from cars to computers, manufacturers are scrambling to source the parts they need to build their products — and audio recording gear makers are feeling the pinch.

Chips are key to building audio interfaces, portable recorders, and any gear that converts analog signals to digital audio. “Integrated circuits serve lots of different functions in an interface…It’s where we load the firmware and the software that make a Focusrite interface what it is,” said Tim Dingley, chief operating officer at Focusrite, the world’s leading maker of audio interfaces for home studios. “In normal times, lead times for these parts are around 16 weeks,” explains Dingley. “Now those 16 weeks are moving to near 50 weeks.”

“The consumer’s insatiable appetite”

The worldwide chip crunch hit right when home-bound musicians were investing heavily in gear to record and stream performances — gear which relies on chips. “Covid and all the various worldwide lockdowns changed consumer behavior almost overnight,” said Dingley. “The huge, huge increase has been in the sub-$500 bracket audio interface market…whether it’s for making music, podcasting, webcam audio — literally everything you want to do now, you need to stream audio or digitize it in some way, and to do that, you need an audio interface.”

“During this whole Covid situation, the consumer’s insatiable appetite for any kind of product is ridiculous,” said Joe Stopka, vice president of sales and business development at TASCAM, the gear maker known for their Portastudios and Model series hybrid mixer/recorders — products initially designed around analog-to-digital converter chips made by Japanese company AKM.

After a well-publicized fire decimated AKM’s chip factory in October 2020, Stopka says, TASCAM “scurried to find those chips at every possible distributor in the world — even to pay premiums for those chips. Unfortunately, a lot of those chips are used in the automotive industry, and we’re just a tiny, puny little industry compared to them, and those guys could pay premiums beyond our ability to pay premiums. So the surpluses of those chips got taken up quickly. Then we turned to other chip manufacturers. We ordered heavily with Texas Instruments, and four months later, TI cancelled all our POs. Demand was higher and they could get more money elsewhere.”

Compared with big automakers, even the biggest audio gear manufacturers are a boutique industry. At Focusrite, notes Dingley, “We’re fighting for parts with companies much bigger than us, whether it’s Apple making phones, or Toyota making cars…everyone is fighting for the same supply.”

The chip shortage has infamously led to Ford and GM building vehicles without chips, then parking the unfinished vehicles, awaiting those tiny-yet-critical parts, for weeks or months before shipping to dealers.

But this so-called “build-shy” strategy, in which products are manufactured just shy of all their parts, isn’t an option at TASCAM.

“Unless we have the full component selection, we don’t even start building something. Because we work on small margins, we can’t afford to have something sitting there we can’t complete and ship,” explained Stopka.

“This insane situation we’re in”

Between devastating fires in the AKM and Renesas chip factories in October 2020 and April 2021 respectively, trade frictions leading to U.S. restrictions on China’s biggest chip manufacturer, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), and severe snowstorms in Texas shuttering Samsung’s semiconductor fabrication plant in February 2021, chips have been in short supply for over a year. “You’ve had all of these one-off events happening at the same time, which has just led to this insane situation that we’re in,” Dingley said.

Why hasn’t chip supply risen to meet demand? While the U.S. Congress recently moved to incentivize semiconductor production onshore via the National Defense Authorization Act of 2021, new fabrication plants can’t spring up overnight, since the manufacturing process for silicon chips is so complex.

“It takes millions of dollars of investment and years to bring new capacity online,” explained Dingley. “So if you wanted to start to build a new fab, it’s probably not going to be ready until 2023.”

With no clear path to increasing capacity in the short term, and customers clamoring for more chip-heavy electronics, the semiconductor shortage has led to a booming secondhand market and sky-high prices on a few high-profile products, like the latest game consoles. “If you try to buy a PlayStation 5, or an AMD graphics card, it’s just through the roof,” noted Dingley.

Meanwhile, stock has dwindled on lower-profile products that the average consumer may not know contain chips under the hood: “People are struggling to buy toasters, because toasters have got semiconductors,” Dingley explained. “And no one wants to make a toaster because no one makes money from toasters.”

So, is 2021 a good or bad time to be a chip fabricator? That depends on your perspective.

“If you look at their financials, it’s a great time to be a chip maker — they’re all making record profits,” Dingley said. “If you speak to someone that works for the chip manufacturer, they’ve probably had a horrible 12 months, because all they’re doing is getting customers ringing them every day saying, ‘I need more chips! You’re causing me line downs.'”

Shipping woes compound the chip shortage

Beyond the chip shortage, audio gear makers are also enduring exponentially higher shipping costs in the wake of the pandemic.

“Not only can we not build as many critical products, but once we build the products, getting them here is costing significantly more,” said Stopka. “Shipping container costs were averaging around $1,800. Then, in the middle of Covid, they went up to $3,800. Now, you can pay almost up to $10,000 for a container.”

Beyond widely publicized mishaps like the Ever Given container ship obstructing the Suez Canal in March, challenges have plagued the world of sea freight logistics since the start of the pandemic. “There is a limit to how many ocean-going vessels can actually float in the shipping lanes on the ocean, and they’re overbooked,” explained Stopka. “During Covid last year, there were 19 miles of ships lined up down the coast waiting to get into the Port of Long Beach.”

Citing shipping costs at “four to five times what they were pre-Covid,” Dingley pointed out that the need for social distancing slows down ports — and that the pandemic is far from over in some parts of the world. “It’s taking longer for the goods to get across from Asia where the majority of stuff is manufactured,” Dingley says. “You’ve got Covid lockdowns happening now in parts of Asia…many factories there are shut. You’ve got Covid outbreaks in southern China, where much of the world’s goods ship from.”

Pivoting to products that don’t depend on chips

So what’s an audio gear manufacturer to do? At TASCAM, the answer starts with a research and development team that’s selective about which products they design and bring to market.

“Our R&D team, as they’re breadboarding products, have to be very sensitive to what componentry will be available,” says Stopka. “Because of the chip shortage, we’re looking at building products that don’t rely on chips, like headphones, microphones…maybe a stereo bus compressor, or a mic pre, or a simple EQ with a limiter that can be used in a studio.”

Stopka, surrounded by gear in his home studio, pointed to a microphone of his own as an example of a chip-free product: “I own over 100 microphones, but right now, I’m talking on a TM-70, which is our $99 version of an SM7, and it’s a great-sounding mic.”

When shipping physical gear is cost-prohibitive, pivoting to building software instead of hardware is one way gear makers can stay afloat. Stopka points out PreSonus as one example of an audio hardware behemoth who has successfully diversified into software.

“PreSonus Studio One is now, I think, the third best-selling and most-used DAW,” he said. “And it’s a great product…representing a pretty significant side of their business now, so they don’t have to rely on just the hardware.”

Stopka is similarly enthusiastic about software that TASCAM plans to release: “We’re going to have some plug-ins this year that are going to look so cool — like Portastudios and 3340 reel-to-reels. They’re so realistic-looking on your screen that you’d think you can reach out and touch them.”

At Focusrite, “Software is already becoming a much bigger part of our business,” said Dingley. “I keep joking internally that we should just sell software for the next 12 months. It would make our lives so much easier.”

All joking aside, Dingley explained, “There’s only so much innovation you can have in hardware products. When you’re actually delivering a great customer experience, software is going to be key.” Dingley cites the on-boarding process for new Scarlett interface users as an example of that customer experience: “Once you buy a Scarlett, you plug it in, and it takes you through a whole tutorial… Holding the beginner’s hand through that process to actually get them up and running making music, is quite a big deal.”

Even guitar giant Fender — whose business is less affected by the chip shortage — has moved beyond shipping physical products, investing in their Fender Play virtual guitar lessons platform that initially launched in 2017. Shortly after Covid-19 lockdowns began, Fender offered a free 3-month trial subscription — a smart move with a captive audience of beginner guitarists. “Last year, Fender had the biggest year in their history,” claims Stopka. “The word was that almost 900,000 people signed up for online guitar lessons… Everybody’s got to look at other avenues of revenue generation.”

“We all seek solace in music”

Pressed for predictions on what the next year might bring for audio gear makers, Dingley is cautiously optimistic: “Everyone’s just going to have to weather the storm and maybe redesign for parts that are available… If you’re in the supply chain world, it’s going to be a tough 12 months. But more people are making music, and that’s a good thing.”

At Focusrite, said Dingley, “I think we’ve hugely benefited from people wanting to spend more time making music.” Looking at Focusrite customers over the past year, he observed, “People who were mainly just playing acoustic instruments are suddenly saying, ‘I’ve got some more time on my hands. Maybe I’ll take the leap and get a bit more involved on the technical side of it,’ and they get a Scarlett Solo or a Scarlett 2i2.”

“In recessions or downtimes, people continue to make music; they continue to listen to music. And I think we all seek, to some extent, solace in music,” says Dingley. “If things aren’t great, we turn to music and create more music at home.”

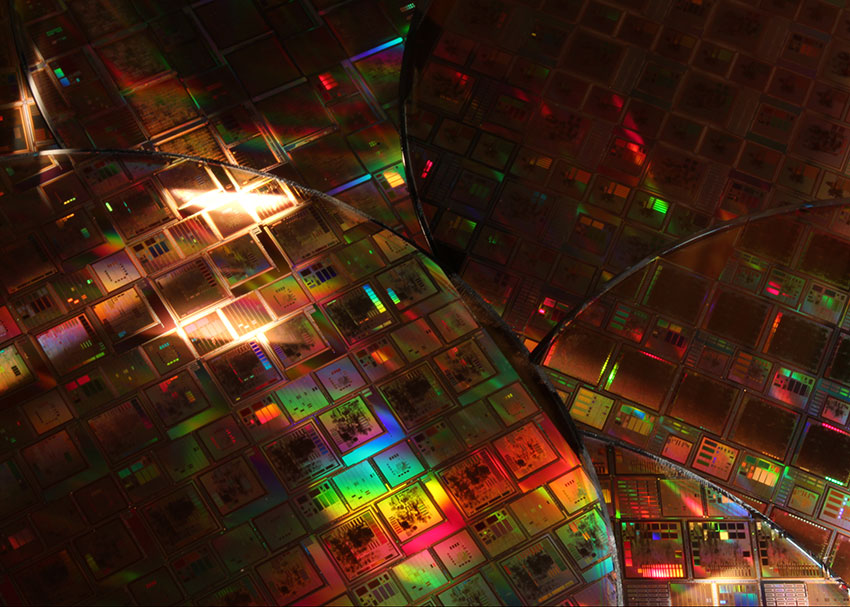

Image credit: “Silicon Wafers Etched Integrated Circuits” by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0