Since its late 2015 release, the Moog Mother-32 semi-modular analog synthesizer has become one of Moog’s fastest-selling instruments of all time. A powerful little synth/sequencer for a remarkably low price, the Mother-32 deserves all the buzz it’s garnered, and then some.

At the Moog Sound Lab in Asheville, North Carolina, we sat down with two of the engineers behind the Mother-32 — Steve Dunnington and Eric Church — to talk about why modular synthesis is making a comeback, what “semi-modular” means, where the name “Mother-32” came from, the proper way to pronounce “Moog,” what they learned from the late Bob Moog, and much more.

Moog production engineer Eric Church

zZounds: Eric, what’s your role at Moog Music, and how did you get your start?

Eric: I work as a Moog Music production engineer. I do a lot of manufacturing design and mechanical design on the products, and I’ve been working for Moog for about nine and a half years.

When I started engineering at Moog, I was a student at the University of North Carolina – Asheville. This was probably about four months after Bob Moog passed away [in 2005]. I was still in school — I had a year left in an audio engineering program — and a flyer on the wall had been put up by the head of the department that had been friends with Bob, saying the Moog engineering department needed an intern.

At the time, it was only Steve and our senior engineer, Cyrill. And I basically came in interning — I spent years just organizing parts, learning the business, the industry, growing, and really learning from Steve and Cyrill. That’s kind of how I got my start.

In school…there’s a large emphasis on music and music performance. So at the time, I was doing jazz guitar. I got tendinitis in my wrist shortly after, so I don’t play very much at this time. It’s become more of a hobby. My rock star dreams got dashed, and I had to take on a real paying job — it couldn’t have worked out better!

zZ: What are some of the Moog products that you’ve contributed to over the years?

Eric: I was heavily involved in the Moog guitar…I was project manager on that. I did a lot of the industrial design on the Minifoogers. I’ve had my hands in most all products since 2006-2007, to some extent — whether it’s just developing the assembly lines ofr manufacturability of the products. Coming from a guitar-playing background, the Minifoogers and the Moog guitar have kind of been close to me.

Moog product development specialist Steve Dunnington

zZ: Steve, how did you get started here at Moog?

Steve: I started working here at the end of 1994…my first real job out of college. I had known Bob Moog, because he used to teach at the University of North Carolina – Asheville. I was one of his students there. I studied music and recording engineering…I studied a lot of different things: classical clarinet, classical piano, jazz piano, electronic music; and I’m a self-taught guitar player.

When I started working here, I wasn’t actually working in engineering. In about 2004, I was actually in marketing, and then I moved over to engineering ’cause I had a technical background — it was more what I wanted to do, so I made that move, and stuck with it since then.

I started in the shop, machining parts. Back then, we were making instruments called the Series 91 Theremins. I spent time working on the lathe — these weren’t computer-controlled machines, either, so it was all very “crafty.” I started working doing simple machining and assembly processes, and then kept at it. There were opportunities along the way. There were only five people when I started, so we’ve grown quite a bit from there.

Dr. Bob Moog and the Minimoog Voyager — the last Moog instrument he worked on.

zZ: Bob Moog was one of your university professors?

Steve: Yeah, he was. Bob taught at UNCA for just a few years in the early ’90s, and you could have electronic music be your focus of study. Which I did for a year, and then switched over to doing some other things. But yeah, he taught synthesis.

We actually used a Synton modular — that was our main instrument that we learned patching and signal flow and whatnot. It was a really odd hodgepodge of gear, ’cause it was a small, small university back then. It was kind of bits and pieces of different types of gear. It wasn’t world-class, but it was pretty — one lesson I got out of that was that it doesn’t really matter what [gear] you’re working with. What really matters is what you’re trying to do and sticking at it.

“That was one of the things Bob talked about: You take an instrument like the Minimoog, and every setting of the dials, every setting of the knobs, is its own instrument, so it has infinite instruments inside.”

The Modular Synthesizer Resurgence

zZ: It’s funny how modular synths are surging in popularity these days, since the original Minimoog came out as a more affordable, less cumbersome alternative to modulars. Why are modulars making a comeback now?

Steve: Well, the roots of all the electronic music we make are based on these [modular synthesis] ideas. Honestly, any electronic instrument that you buy is a modular instrument. It’s just, how many choices do you get to make as a user of it, versus how many choices were made for you in order to simplify its use?

In the case of the Minimoog, you know, the whole idea was, well, we’re demonstrating our modulars, and we’re going to have to make the same patches every time, and it takes all this time to set it up. You know, if we want to just show somebody what this thing can do, it would be nice if the wires were already there.

The transition was, the wires were on the panel, and they went underneath the panel. I guess people really like choices today…they want some sense of control over the signal flow and what they’re doing. That’s one cool thing about modulars…you are setting up the instrument. It’s not done for you.

The original 1970 Minimoog, Photo: Wikipedia

Eric: You see it; it’s all there on a panel — it’s not just behind the hood, and the magic happens and the sound comes out. You’re actually a part of it…

Steve: Every patch that you make is its own instrument. That was one of the things that Bob talked about, that I remember: You take an instrument like the Minimoog, and every setting of the dials, every setting of the knobs, is its own instrument, so it has infinite instruments inside. And what the musician does with that — honestly, it’s kind of overwhelming to a lot of musicians! And that’s why in some cases it’s really good to maybe limit a little bit, so you don’t have to think about “What infinite instrument am I going to play today? I can’t decide.”

Eric: That’s why we like presets.

zZ: On instruments that have presets, who gets to come up with the names of all the patches?

Eric: Whoever designs them.

Steve: Yeah, whoever does that sound names it. That’s part of your job. There’s always the editing of the names, though.

zZ: Everyone wants their patches to be all naughty words? Like “Fat F*cker”?

Steve: Yeah. Those get edited out.

zZ: Right. Did you guys work on the Voyager XL at all? I ask because it has presets, but it also has modular capability.

Eric: We were both involved in the XL side of that, which is where it really does tie in to its modular roots…Steve was here for the original Voyager.

Steve: When we did the Voyager, before it was the Voyager…we had the Moogerfoogers, right? Which was kind of the idea of a modular synth module, but with a stompbox approach. So you didn’t have to buy a whole system; you could buy just the standalone module…you can turn it on and off like a stompbox, or you can patch it to other things, and all of a sudden you’re into modular synth world.

So we had that already, and Bob was really into that idea of the classic Minimoog, but not just recreating it. What would happen if you added all these little points, like these inputs on the back? And we added the little output connector so you could have the VX-351 CV Output Expander. And then it went further than that. When we were actually designing the circuit — well, when Bob was actually designing the circuit — he was listening to all kinds of ideas on that. Notice on the original Minimoog, and also on the Voyager, that each section is a module, and it’s got a lot of ins and outs, and you can do quite a bit of stuff with it.

Inside the Moog Mother-32

Inside the Moog Mother-32

zZ: Tell me about your work on the Mother-32. How were you involved in the design process?

Eric: I did a lot of the industrial and mechanical design. And artwork — the look of the product.

Steve: One of my jobs was working on designing the circuit board — the schematic and the circuit board layout.

zZ: How long, from start to finish, was the design process?

Steve: That’s top secret! No, just kidding…So we have a long, long list of product ideas…we’ve had some projects that were on a really short, quick time scale, like 6 months. And some of them take much longer. This one was somewhere in the middle: a little over a year.

zZ: Is the Mother-32 the first Moog semi-modular synthesizer?

Steve: It’s the first tabletop, really serious semi-modular that we’ve done. You know, the Little Phatty had some in-and-out capabilities. The Sub Phatty and the Sub 37 have some input capabilities. The Voyager, of course, has a lot of inputs and outputs, and we have the Moogerfoogers. But we’ve not done a tabletop standalone analog synth this way before. It’s pretty new for us.

zZ: Can you describe the design? What’s new and different about it?

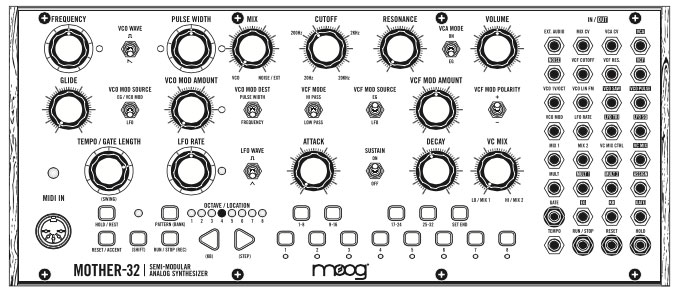

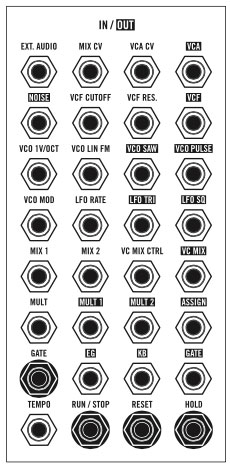

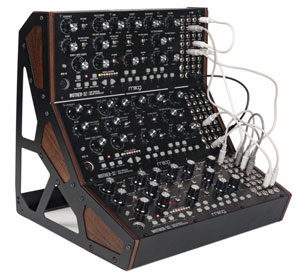

Steve: Mother-32 is a tabletop semi-modular analog synthesizer. It’s got the panel that you interact with, the playing panel — and then you have a small keyboard that acts as an interface to the built-in sequencer. And then to the right it has a patch panel.

As far as the voice architecture of the synthesizer, it’s very, very simple: You have a single VCO (voltage-controlled oscillator), you have a noise source, one VCF (voltage-controlled filter) that can be either low-pass or high-pass, and one VCA, and then some simple modulation capabilities. So with nothing plugged in except for the output, you can make sound with it. That’s the “semi-modular” part: We did connect some wires behind the panels, so that if you’re not familiar with modular, and you get it out of the box and you want to make some music, you can do it right away.

The patch panel is really there to multiply the possibilities. Every electronic music instrument is essentially a modular piece of gear — it’s just a matter of how much freedom you have. And so the modules inside the Mother-32 — you do have access to them; you have inputs and outputs, or “gozintas” and “gozoutas” as we like to say. So you can hook things up how you want to make the sound more complex…if you have a modular setup, or a Eurorack modular setup, you can integrate it with that really easily.

“The Mother-32 is semi-modular, so you don’t need patch cables to make sound. You can learn what the oscillator does, what the filter does, what the VCA does — without the patch cables. And then, after you learn what those things do, you can start adding patch cables…”

zZ: What prompted the decision to design a Eurorack synth?

Eric: We were designing a really powerful tabletop synth, and we’re looking at it, and we decided, “Well, if we’re creative with how we approach this, we can expand the versatility by making it Eurorack-compatible.” So by planning ahead, and discussing how we wanted to approach the mechanics of it, we were able to achieve that.

Photo gallery: Look inside the Moog factory

zZ: What does Eurorack actually mean?

Steve: Eurorack isn’t really an official standard, like you would say MIDI is a real standard, but Eurorack is kind of a very loose standard. It’s actually based on a test-equipment mechanical standard. As far as it pertains to synthesizers, it’s a fairly loose set of rules that say, “These are the divisions of spacing; they’re called HP…if you make your module this high, then you’ll fit in the system, and if you have these electrical requirements, you’ll fit in the system.” That sort of thing.

It was [German analog synth manufacturer] Doepfer, of course, who kind of pioneered Eurorack, and they still make great stuff. It’s taken off in popularity. We’ve had customers who integrated all our existing products into their Eurorack systems — you just need a cable that goes from quarter-inch to 3.5mm. And all of Moog’s stuff actually plays well with Eurorack stuff. If you have a Eurorack setup, you can just plug straight from our stuff into your stuff…the Mother-32 is our first time where we made something that doesn’t need a cable adapter.

If you’re new to Eurorack, it seems really complicated, but in fact, it’s not. It’s kind of simpler, because if you’re dealing with just a module in the world of modular, it’s less stuff. It’s just when you start to add different modules and you start to multiply the possibilities, that it gets complicated.

“If you like exploring things — if you’re a curious person — modular synthesizers are really pretty addictive.”

zZ: The Mother-32 has a much more beginner-friendly price point than, say, a Voyager. So how do you address usability for a beginner synthesist?

Eric: One key thing is, we always want our gear to sound good. So when you turn it on, it needs to sound good. And to a beginner, I think that’s really important: to be able to turn it on and make noise and have really cool sounds coming out of it.

Steve: There’s a couple ways that we approach that. Our manuals are pretty good, I think. We have a forum where you can go and ask questions. We have really good tech support, also. So you’re not there by yourself, necessarily, learning these things.

But the principle of modular synthesis is really pretty simple. You know, you have some sort of signal source, and it has an output, and then it’s gonna go to the next thing that has an input. You just break it down into, what are your signals that you’re listening to, and then what are the signals that you’re using to change the sound — and those are the things that people typically talk about being Control Voltages, right? So you can make your frequency, or your pitch, go up and down. If you actually look at it on an oscilloscope, you’ll know it’s a voltage that goes up and down that makes that happen. So the principles are actually pretty simple — you just have to get used to it.

For instance, with the Mother-32, it’s semi-modular, so you don’t need patch cables to make sound. You can learn what the oscillator does, what the filter does, what the VCA does — without the patch cables. And then, after you learn what those things do, then you can start adding patch cables and learning. “How does this route to this, and what does it do?” If you like exploring things — if you’re a curious person — modular synthesizers are really pretty addictive, actually. They’re really fun, and it’s hard to stop thinking about some of the things you can do, if you like them.

zZ: Tell me about the name “Mother-32.”

Steve: Well, you know, naming a synthesizer product is always interesting. You have the approach where you can be just like, “Okay, this is the XJ97-whatever,” or you can have a funny name, like “Moogerfooger,” or you can combine both the approaches, as in the Mother-32.

The idea sort of came from science fiction movies. Alien has this computer named MU/TH/UR 6000, you know. And then the word has all the other connotations, like “Ooh, it’s a bad mother,” or “It’s the mother of all things.” It’s a very powerful word, and and it’s a powerful little synthesizer. And the “32” part: there’s 32 steps that you can have in a sequence, and there’s also 32 patch points on the side. So there’s your 32.

It’s always a challenge naming some things. If you don’t like the name, you don’t have to worry about it. It still sounds great!

Alien‘s MU/TH/UR 6000 computer — one inspiration for the name “Mother-32.”

Defining the Moog Sound

zZ: What does “the Moog sound” mean? Does it have to do with specific components and the way they’re put together? Or is it really more than the sum of its parts?

Eric: It’s components, it’s design… The Moog sound is just this really smooth, full sound. You can really hear the Moog sound on a lot of older recordings. You can hear it coming back into a lot of modern recordings. And it just has this fullness that you can’t really put words to until you actually hear it.

Steve: I’ve had a couple instances where artists are playing or performing…for instance, Herbie Hancock was playing a Voyager at the City Center, and as soon as he started playing it, people got up and started dancing. I mean, it also had to do with what song he was playing, but it was like a sort of change in the room. I mean, when you put a Moog on big speakers, there’s something very pleasing about the sound. You kind of feel it in your guts.

Eric: I’ll get asked a lot in old recordings from friends, “Is that a Moog? Is that a Moog?” It’s like, “Nah, that’s not a Moog.” And then the song will change, and it’s like “That’s a Moog.”

I definitely kind of equate it to — not to put this on the same level, by any means — but like, a Stradivarius. And they’ve looked back to like, its wood that had a certain climate at the time it was growing, and it gave the wood this tonal characteristic that people seek.

I feel like our products really have life to them. It’s not like a lot of digital synthesizers, where it’s always the same. You come across the same circuit built at a different time, and it might have a slightly different color. You really work to tune it and get consistency, but it just has this life to it that you really can’t expect from an electronic circuit or a software synthesizer.

“The Moog sound is just this really smooth, full sound. You can really hear the Moog sound on a lot of older recordings…it just has this fullness that you can’t really put words to until you actually hear it.”

zZ: And that’s why I should get a Moog instead of a software synth. Right?

Steve: Well, okay, I want to say something: Bob wasn’t a purist about analog versus digital. He wasn’t! Analog versus digital — they’re both tools. Sometimes it’s convenient to work on your laptop. Sometimes it’s very convenient to turn that computer off. And the hardware stuff and the analog synth, it’s right there — you’re connecting to the circuit, you know — and how that makes you feel and react; that’s really up to you, the user. But I’m here to tell you that in my experience, you go straight to making music with a hardware synth, whereas in a computer it gets back again to having too many possibilities. Sometimes it’s kind of crippling, creatively. So turn off the computer sometimes. Use your hardware synths. Make music.

Eric: Especially if you’ve learned to play on an instrument, that’s where your creativity comes. That’s where you feel what you’re playing — on the instrument you learned on. And when you take that away, and you put a computer in front of you — especially if it’s something you’ve worked on for writing papers, doing schoolwork, accounting, whatever it might be…a computer can be a really musical device, but it’s just not what you were trained on musically.

“Bob wasn’t a purist about analog versus digital…they’re both tools. Sometimes it’s convenient to work on your laptop. Sometimes it’s very convenient to turn that computer off…So turn off the computer sometimes. Use your hardware synths. Make music.”

Herbie Hancock’s synth rig, from his Sunlight album’s back cover, 1978.

zZ: What musical instruments do you have in your rigs at home?

Eric: A lot of acoustic instruments. I spend so much time at work working with all this great electronic gear, so when I get home, I don’t have as much time to spend making music, and I just pick up an acoustic guitar, or sit down at an acoustic piano, and that’ll be my creative outlet outside of work.

Steve: Yeah, I have an acoustic guitar. I do have a crazy setup of stuff — I don’t get to it as much as I would like. Working on the computer all day, I don’t typically get home and want to turn the computer on again. I have all the Moogerfoogers, I have a Voyager rackmount, I have a Voyager — I have some stuff!

zZ: Going along with that idea of getting home and not wanting to turn on the computer — tell me about the step sequencer on the Mother-32.

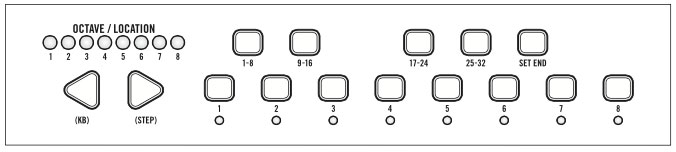

Steve: Well, when we did the Sub 37, we added a step sequencer to that instrument, and it is fun. So when we were envisioning the Mother-32, that was one of the things we wanted on there — and we thought of some very clever ways of making it very small and actually squeezing it into this form factor, which was really a challenge.

You can use the Mother-32’s sequencer in a couple ways. One way is a very simple step entry, where you play the notes and record them in, right? I mean, it doesn’t record a real-time performance — you’re populating a list of notes and rests and accents and things like that. And that’s great…you can go very far with that. But as you’re playing it back, there’s another mode you can go into where you can, in real time, turn steps on and off, or edit them, and so it’s designed to be a performance or non-performance sequencer, depending on how you approach it and how you’d like to use it. It’s pretty flexible. It’s a lot of fun. If you get two of them — and then three of them — you start to have an orchestra of things happening. Yes, I’ll be getting more than one.

Eric: At least five.

Steve: I think three. Maybe five. They’re small, so they don’t take up a lot of space. You can have a few of ’em!

zZ: What is it like to work for one of the most influential companies in history?

Steve: Well — influential in the musical instrument and synthesizer business. Let’s put it in perspective a little bit!

What’s it like to work here? Well, I’ve been doing it for a long time. I wouldn’t be doing it if it wasn’t rewarding and fun. One of my favorite parts is when you’re working on a circuit, and you know it’s going to be pretty good, and then you get it to make sound, and you listen to it for the first time. That’s always really exciting, when you hear your oscillators oscillate and your filters filter.

Eric: I grew up having my dad tell me about Moog — and to have had a chance with a company like this, and to still be with a company like this, and to play a role in that — it feels nice to be a part of history, in a way.

zZ: And finally, how do you get your customers to say your company’s name right?

Eric: I always equate it to the way people say “Porsche” — if the last name was [pronounced] “Por-scha,” then that’s what I want to say. And so there’s multiple different pronunciations, if you go back to Germany — “mogue,” “mook” — but I try to stick with what was the guy’s name.

Steve: It rhymes with “vogue.” That’s why they did the Moog Rogue — it rhymes! But in Britain, you can never get them to say Moog. It’s really funny…I’ve learned to move on!

Watch our exclusive Mother-32 video demos

Leave a Reply