Welcome to Beat Connection, a series dedicated to promoting modern and vintage dance styles the only way we know how…by providing you a musical starting point to help you create that beat. In the majority of our recent posts, we’ve been taking you on a journey to what I’d dub “foundational beats.” These foundational beats are standard rock, pop, funk, R&B, and dance beats that every producer should know the ins and outs of. In our previous post, we looked at the production techniques behind some of trap music. Today, we’re taking an extreme detour, to ground ourselves in a different style. This is our look at binaural recording.

Go outside. Shut the door.

- Brian Eno, from Oblique Strategies

The ear, unlike some other sense organs, is exposed and vulnerable. The eye can be closed at will; the ear is always open. The eye can be focused and pointed at will; the ear picks up all sound right back to the acoustic horizon in all directions. Its only protection is an elaborate psychological system of filtering out undesirable sounds in order to concentrate on what is desirable. The eye points outward; the ear draws inward. It would seem reasonable to suppose that as sound sources in the acoustic environment multiply – and they are certainty multiplying today – the ear will become blunted to them and will fail to exercise its individualistic right to demand that insouciant and distracting sounds should be stopped in order that it may concentrate totally on those which truly matter.

- R. Murray Schafer

What is Binaural Audio?

Why binaural production? We all know and comprehend the two most used forms of audio recording. Mono recordings take one microphone, pointed at one direction, and capture that sound on one waveform that’s evenly split, left and right. Stereo recordings take one microphone (with stereo pickup elements) or two or more microphones, and point them at many directions and sound sources, then combine them all through two waveforms split left and right. Now imagine this scenario:

You’ve gone to a coffee shop to hear your local acoustic guitar trio. You grab your coffee, plop down, and sit right in the middle, in front of this group. To the left, right, and center of you the group is playing all the same tune, in harmony. Immediately a bee enters the stage causing each to stop playing and fidget around. As the bee starts to attack one of them, that player gets up and runs to the opposite side of the stage, screaming in distress. Somehow, audio was captured of this moment.

On a mono recording you’d just hear all the mic’d up members performing, then the performer being attacked getting up and running away. On a stereo recording you’d hear all the members performing, panned to the direction they’re situated in front of you, and (eventually) hear the bee enter coming in and out of different directions, as the member running off stage, gets picked up by all the microphones, screaming in distress. On a binaural recording, things are different, while you can hear each member performing like before, on this type of recording you’d actually hear the bee’s journey to the stage, all the way to the moment it chose to attack the member on stage, plus some commentary from the peanut gallery around you. As the member’s screams get lower in volume as he/she darts across the room, you’d also hear exactly the direction they took and which member, somehow, continued playing — perhaps in a different chair now?

The problem with what we’re accustomed to hearing in normal studio recording is that as a sentient creature with two ears and two eyes, we perceive sound as more than just a panoramic picture panning left to right. Normal music production requires us to hear music in a flat dimension. If a guitarist was performing on the right side of the stage, he shall remain on the right side of that sound stage, when the mixer’s pan knob gets twisted right. Binaural production adds a third dimension, depth, through multi-directional microphones that capture movement, spatial placement, and amplitude dynamism these other forms of recording lack. Binaural recordings sound true-to-life because they actually capture sound as one would hear it occurring in real life, in real time. There is no pan control; where you hear the sound coming from is exactly where the sound came from, in real life.

In our age of surround sound, we tend to forget that binaural recordings existed long before we even had a notion of what Dolby Atmos is or what the latest 3D audio plug-in does. Binaural audio was a product of the late 1800s when early sound recorders discovered one could mimic what the ear hears simply by placing microphones at a distance and in a placement to emulate how one’s own noggin would pick up sound naturally. How would one then reproduce this same audio experience for playback? They’d go in reverse, piping this audio through specialized headphones that’d pick up this audio signal and present the listener the sonic experience of being there (wherever that there was).

Due to the lackluster popularity of such headphones, the increasingly expensive gear required to record binaurally, and the huge popularity of audiophile hi-fi systems which would never be able to reproduce the close-listening experience required of it, the dearth of binaural recordings should be of no mystery to us. No one had time or money to shell out for multi-speaker systems required to properly reproduce them. It isn’t until the rise of the Walkman and our current tune-in and-headphone-out times, that smartphones and other portable devices have ballooned the popularity of such recordings.

Recording studios never had the need to record with binaural equipment. It’s easy to imagine why. The illusion of a guitarist sounding as loud as a drummer is just that. There is no way we’ll ever be able to sing as loud as a 4×12″ speaker cabinet. Standard stereo recordings capture audio, modify its dynamics, and manipulate sound to fit someone’s specific artistic vision. For this very reason, you can understand why binaural recordings are now the mainstay of field recorders and orchestral recordings. When you want to capture life as it is, and as it moves, you go binaural.

Going back to why I chose this topic, I chose it because I do believe there are ways this production technique can be part of your knowledge base. Binaural recordings can be musical. One can go back to Lou Reed’s pioneering work on Street Hassle, its form trying to give you the lived-in feeling of actually sitting in on his recording session, but I’d rather look elsewhere. For me, it began in hearing the music of Japanese artist Takashi Kokubo.

In Japan, a new form of music therapy was made popular during the rise of its ’80s bubble economy. Known as sound bathing, customers would attend shops, somewhere in their local industrial megacity, and retreat to a musical space where the sounds of forests, sea, and nature as a whole, would be reintroduced into their life (and in turn), reintroduce them to an immersive, sensory environment not easily attainable in contemporary, urban Japanese life. It was for these places that Takashi Kokubo wrote music. Before recording even existed, humans had used bowls, gongs, shruti boxes, and other resonating instruments to envelop you in sound, as a means to something else. Binaural recordings, at least to me, sound like an extension of this through technology.

For Takashi, he’d take an early Neumann KU100 binaural dummy, this unlikely microphone contraption, into the forests, beaches, and other natural environs of Japan. Once in his studio, he’d put those recorded binaural sounds to tape and combine them with stereo music influenced by the ideas of music therapists who theorized listeners felt comfort, or would feel certain therapeutic benefits (alertness, focus, relaxation, etc.), when they’d hear sounds recorded, performed, or tuned at certain frequencies. Binaural beats, or to be more precise to his world — alpha wave 1/f fluctuation music, was/is synthetic resonating instrumentation woven into the binaural environmental recordings as a means to both immerse the listener into something they can’t physically be in and to add that extra oomph of indescribable meditative music.

Quite literally making music to be listened to while inside your air conditioned room, Sanyo commissioned Takashi to take his sound design ideas and place them in music that can get you inside the atmosphere of a seaside locale. It was refreshment music for those that needed refreshing.

Now, can I prove that this kind of music works? No. My point is to prove how much different music or video sounds with a binaural track in it.

Divorced from their music, these recordings show an immersive quality that is a far better documentation of the ecology as it is than any stereo recording would allow. Take the same equipment to the city or to another sonically interesting locale (think of a park close to church bells or a carillon) and you’ve got something that really stands out when heard through headphones. Put it on, and record yourself speaking, and you’ve got yourself something far more personal-sounding than any ASMR video upload. 360-degree VR video was made for this.

What will we try to do in this post? We’re going to use modern tools to literally hear and appreciate the difference.

Binaural Recording With Binaural Devices

For the purpose of this post, i’m going to use two different microphones to show the difference between audio captured by binaural microphones and omnidirectional stereo microphones.

Sennheiser Ambeo Smart Headset Binaural Recording Headphones – Gone are the days that you actually need a binaural dummy or tricked out microphone setup to record in place. Sennheiser’s Ambeo smart headset literally stuffs four pairs of omnidirectional microphone, (two pairs in each earbud) and lets you simply plug into your iOS device and hit record on your Camera app to start recording binaurally. A fascinating bit of technology, the Ambeo replaces the old dummy with your head (we’ll let your significant other decide if you’re still the dummy), and puts the microphones exactly where they’d be in the old standard binaural setup.

Sennheiser Memory Mic Wireless Clip-On Microphone – The concession of video recording from large steady-cams to much more portable, everyday man camera phones doesn’t mean that audio magically got better. What we’re realizing is that audio fidelity has largely remained poorly the same, even as phone camera sensors have gotten to be as good (if not better) than older, larger video cameras. Sennheiser’s Memory Mic does something ingenious: it supplants your built-in mic or headphone microphone with a clip-on omnidirectional microphone that can capture audio as you hear it, a much higher fidelity than these same microphones. Through your phone’s Bluetooth connection, you can capture audio wirelessly on the move.

Here’s how my setup looks, once it’s all said and done:

Quite literally all you need to be a binaural or stereo field recorder is a single iPhone and one (or both) of these Sennheiser devices. Since the Sennheiser Ambeo Smart Headset terminated with a Lightning cable connection, I had to jerry rig a setup where I used my iOS tablet for video and binaural audio, while my Android phone would stay connected to the Sennheiser Memory mic, recording stereo audio that I could later sync with the tablet video. Note to Sennheiser: please introduce an Android version of this headphone or offer an adapter that would allow it to work with modern Android devices.

Field Recorder Notes

On iOS, the Sennheiser Ambeo Smart Headset works without any extra software. Simply connect your headset, fire up your Camera or Voice Memo app, and record away. All audio that is recorded binaurally remains in the same fidelity as it is woven in with the video. In essence, it supplants your iOS device’s audio, letting you both record and monitor what you’ve just captured. Since the Ambeo is a joint venture with Apogee, Sennheiser provides a brilliant little free app that lets you fine-tune the recording levels (for natural or high noise areas) and also lets you dig into the headphone features which include some beyond-nifty things like enhanced “True-to-Life” hearing (basically treating your headset as a sound amplifier, (letting you feel like you have superhuman hearing) plus creature comforts like active noise cancellation for day-to-day listening.

On Android and iOS, using the Sennheiser Memory Mic is a bit different. First of all, kudos to Sennheiser for using a pliable magnetic microphone clip to secure this device to your clothes. Since the Memory Mic is completely battery-operated and wireless, I can’t stress enough how important it is to simply just slide it onto your jacket somewhere and forget about it. Its four-hour runtime makes it convenient enough to just turn on when you need it and leave it on until you don’t. What makes it a bit of a turn off to use are the few hoops it requires you to jump through to simply capture audio. Unlike the Ambeo Smart Headset, the Memory Mic requires you to go through a proprietary app to capture audio or video with its audio. If you like your camera app, forget about using it here. Then, to compound that problem, every time you capture something, it will ask you to synchronize your Memory Mic with your phone, dumping stored audio from its memory chip into your phone. The sync process can be slightly infuriating since it makes a wireless connection which takes a short bit to take, time you could be using to capture something else. Then again, just the ease of having to what amounts to an ultra-portable clip-on omnidirectional microphone in your pocket trumps the nag-worthy things that arise from using it.

How did both work in the field? On very crisp Chicago autumn days, one word came to mind: windy.

Field Recording Notes

At this time of the year, folks aren’t joking about Chicago (this author’s current home town) being the Windy City. In between fighting bouts of gusts and gales that would send each microphone into a noisy fit, each microphone proved adept at capturing the subtle nuances of a bird singing while flying nearby, a pond or lake lapping up a shoreline, and distant conversations carrying on, coming slowly closer, as they traversed your kind author’s path. I would appear to be selling out by saying that: “the Sennheiser Ambeo Headset actually recorded life as I heard it,” but as I pressed the big red stop button and played back each recording, each time (upon close and not so close headphone hearing) I was shocked to hear that it sounded like I was still there — that there I lived just mere moments ago. I never had the distinct feeling of hearing something on my headphones coming towards me, only to stop and realize it’s what I already recorded, as I did on the Ambeo.

This would be what would separate the recordings made on the Sennheiser Memory Mic. On the Memory Mic, as crisp and detailed as those recordings were, they lacked a certain depth to them. It’s as if they sounded flat (spatially/sensorily), when compared to their binaurally recorded counterparts. Gut feeling is not something you or I can describe, but scientifically, whatever Sennheiser did to capture the spatial connection in sound, was there on their Ambeo recordings. In the following examples, hopefully, you’ll be able to appreciate these differences.

NOTE: Headphones are required to hear the full effect of a binaural recording. Turn the volume up until a natural level is heard.

Stereo – Omni vs. Binaural Recording Examples

Lakefront Recording

In this first example, I took these two set of microphones to our fair Lake Michigan shoreline, specifically to the historic and quite picturesque Captain Daniel Wright Woods Forest Preserve in Mettawa, Illinois to give you a sense of spatial depth between the two. Notice the flat evenness of the stereo recording. Then, notice how on the binaural recording you can appreciate the movement of the water below you from right to left, in a linear, natural motion.

Pond Life Recording

Here is a great example of how static sound-producing objects sound when captured by both mics. Recorded on a very windy day at the natural oasis of Mallard Lake in Hanover, Illinois, one can appreciate how the easterly drifting wind tends to drown out most of the recording with only the most cutting of wildlife noises sneaking through. However, upon closer listen, notice how on the Memory Mic the sounds of the insects tend to remain (once again) flat and hazy sorted melting in with the assorted sounds of hikers, birds, and other creatures of in the distance. On the Ambeo, once the wind subsides, you can clearly point out what sound it is you’re hearing and where it lies in relation to the listener. As you hear it, I heard it.

Trail Recording

We’re back at the Captain Daniel Forest Preserve in Mettawa. On this more subtle recording what you’re looking out for is to appreciate things directly in front of you, out in the distance. On the Memory Mic you can hear it capture sound but it seems to be missing a few things the Ambeo does capture. On the Ambeo mics situated above are able to more intimately zero in on items at the distance and above your fair listener’s head. That faraway flock of migrating geese, and what sounds like either neighborhood dogs (or coyotes!) appear, somewhat clearly, as living things, creating noise around us.

Binaural Recording as Sonic Canvas

We’ve heard and seen so far what you can appreciate as sonically different between binaural recording and other forms of recording. Let’s take it a step further and see what you can do to create a different kind of multimedia content point.

In this first video I spliced together simple scenes from downtown Chicago that feature rich immersive audio that takes full advantage of the Sennheiser Ambeo’s spatial recording possibilities. Sound sources as simple as a train moving by, pedestrians having conversations, and skaters taking advantage of the local Art Institute’s park, allow you to weave a little tapestry of city life, in a way that sounds more vivid than before. Would you want to do this with every sound recording you do? Maybe not, but for things where you value mobility and spontaneity to capture, doing this type of recording seems like a must to try out.

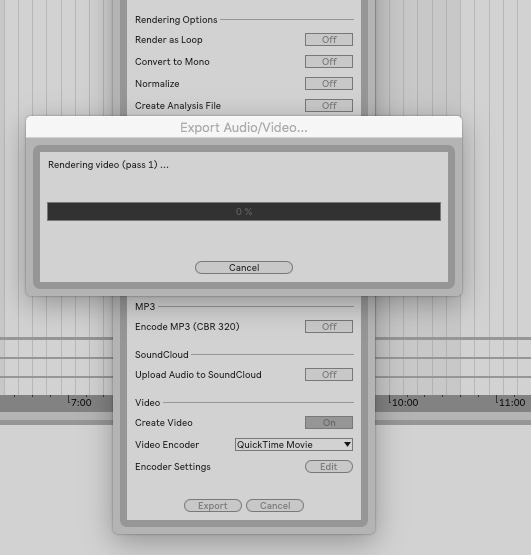

Using Ableton Live With Binaural Video

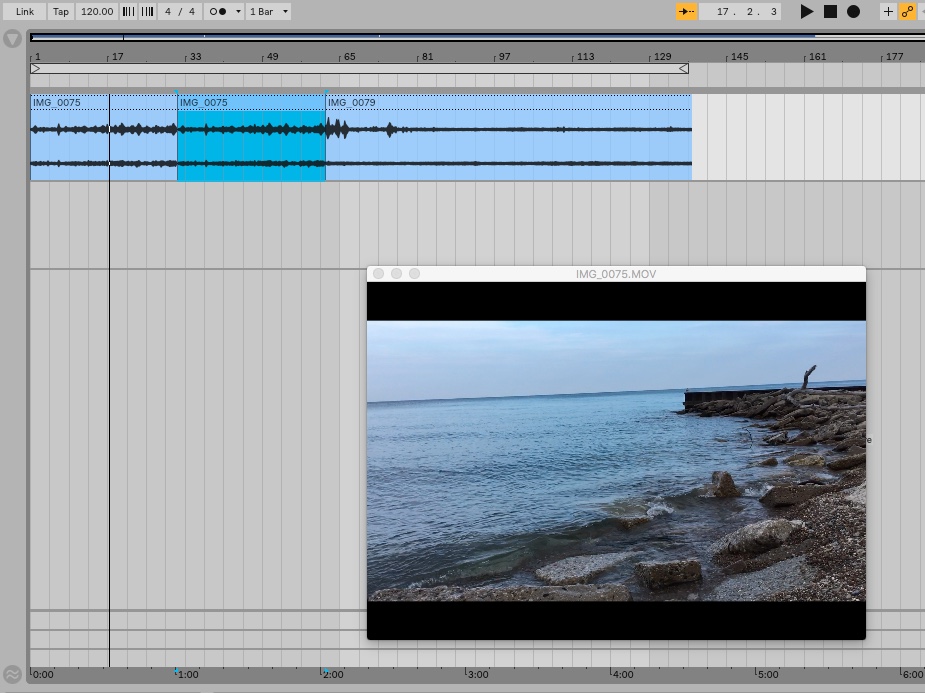

This final section is a simple one. If you’ve ever used something like iMovie or Final Cut, editing video or working with audio and video usually involves simple tasks like dropping in audio and setting start and end points. Video itself can be a cool format to use outside of the mainstays of video recording. In Ableton Live, you can actually import video and add a soundtrack to binaural recordings, as part of the Session view you know and love. On Ableton Live here’s how you do it:

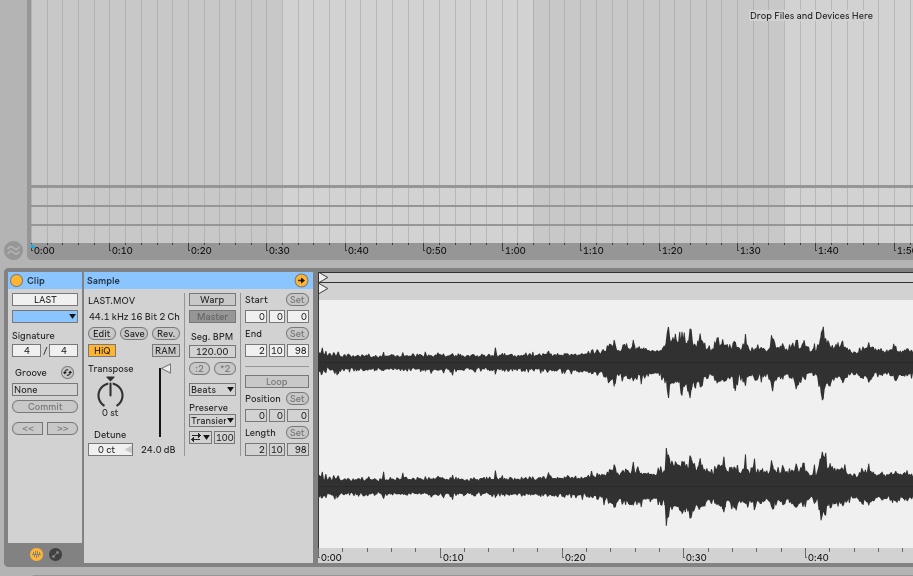

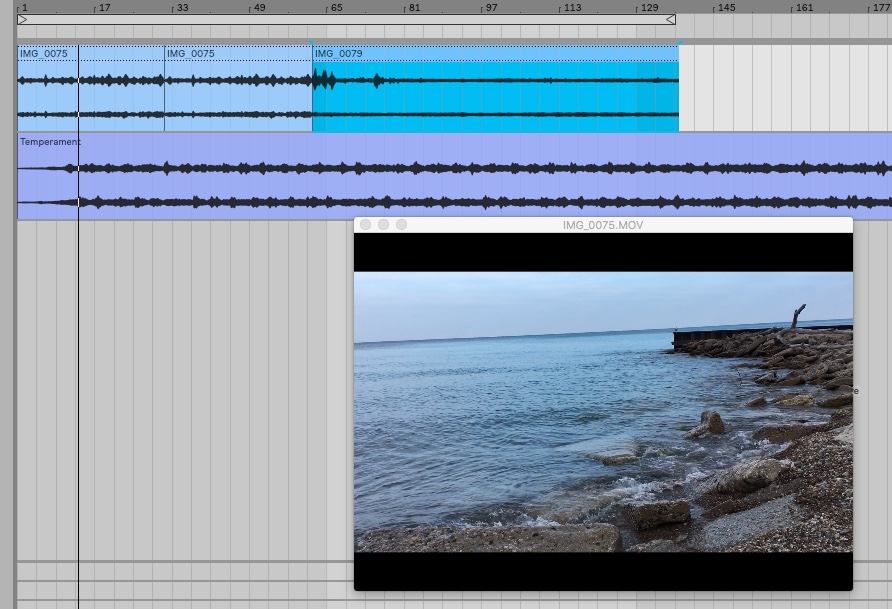

Nothing changes from what you know. You drag your movie file onto an open audio track and instantly Ableton creates an audio clip of your video’s audio. From there you can see a viewfinder window opens up letting you preview your video when it plays. An important thing to note about working with Ableton Live is that video follows the tempo of the master recording. Unless you want to see video play either too quickly or too slow, you need to change two important settings on the audio clip of the video: Warp and Tempo Master/Slave.

Seen above, you have the ability to warp and time-stretch any video’s audio that’s imported into the Session View. Usually, if you have a composition already written, what you have to do is both turn off [Warp] and click on the [Slave] button to turn it into the Master. Once you do that the video should play at it’s own tempo without any artifacts that Live’s time-stretching would have incurred. After that is done, you can freely add any audio effects into the track. As also seen above, I duplicated one video and added part of another video to make a longer form video.

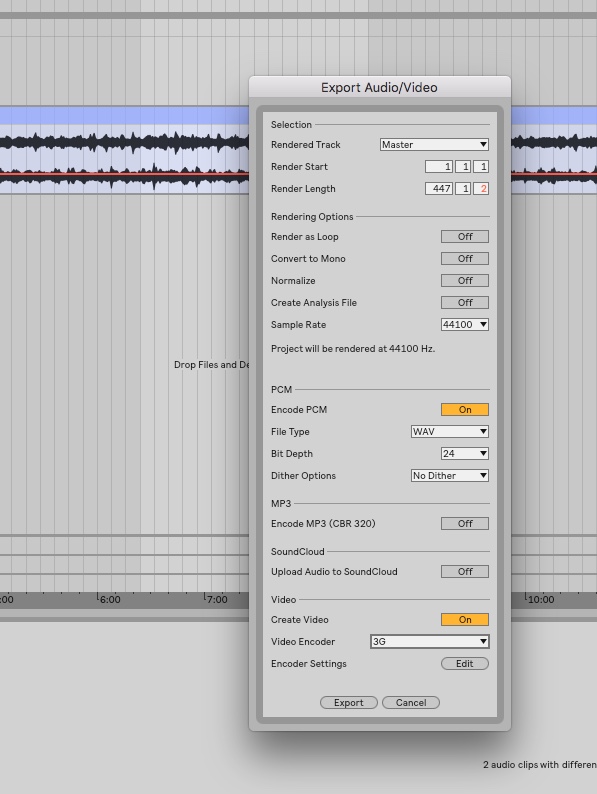

On this binaural sound recording, you’ll see that all I’ve done is layer another pre-recorded track onto the timeline, giving it the soothing soundtrack (I think) it was meant to have. When you’re ready to export this new video, selecting Export Audio/Video… now presents you with an option you can tic On to do so.

With a plethora of options available to you per encoder, I won’t go into what you can do after this step. What you can do is export a completed video file at the resolution and time settings you wish for formats made for iPad, Flash, DV, and others. Pretty neat options for a DAW to have, right?

Throw it up on your favorite video editor to add some titles, upload it to your favorite video streaming site, and voila, you’ve got some meditative video for others to enjoy.

Throw it up on your favorite video editor to add some titles, upload it to your favorite video streaming site, and voila, you’ve got some meditative video for others to enjoy.

All images, videos, and songs by author.

Leave a Reply