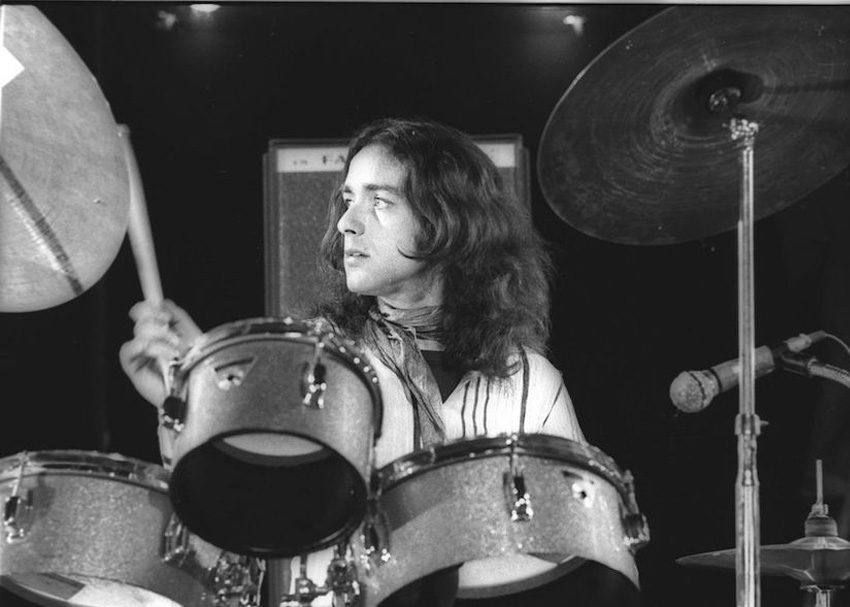

With the news of Jaki Liebezeit’s recent passing, what better time than now to take a look back at his influential body of work? Let’s begin where it began. “Communism, anarchism, nihilism” — those were the powerful words rumbling through Jaki’s head in 1968. Christening the band CAN — a move away from their original name Inner Space — meant an acceptance of something far more direct. Trying to cement a future Jaki had been struggling to grasp, those words would shape the musical philosophy that would guide his career. A life constantly searching for some answer, finally had its response.

Rise From the Rubble

Jaki was born in Dresden, in 1938. Tasked to survive during the worst time to be born and raised in that German city, Jaki was thrust into a generation of Germans forced to create a new culture from rubble. Jaki wasn’t much like any other teenager. Trying to make it as a musician for a living, drumming was a job first and foremost. Performing for American troops stationed in the American-occupied city of Kassel made Jaki quickly realize that being in a rock-n-roll band was not where his future lay. So, rote and simplistic was the music, that performing it seemed more of a chore than anything else. Jaki wanted to do more than just earn a mark. Maybe jazz held the answer?

“Free” Jazz

Jaki would travel to Barcelona and try his hand as a jazz drummer. Appearances playing alongside Chet Baker led to him being hired as a drummer for European free jazz pioneer Manfred Schoof. Initially, Jaki thought he found the kind of music he wanted to play. In short time, he’d discover how much jazz could also hold him back.

Drawn to the music of Africa and India, Jaki figured out that the free jazz music he was being tasked to play wasn’t really that “free.” Simply put, there was no room for space, flow, and repetition. In this other music, Jaki heard repetition and space. So he asked himself: why wasn’t that allowed in jazz? Fate had it that Jaki would be led on a path to musical self-realization. Jaki would discover exactly what he’d always wanted to play. Somewhere out there, others were searching for the same answer.

The Exploding German Inevitable

In the mid ’60s, two young musicians, Irmin Schmidt (keyboardist) and Holger Czukay (bassist) encountered the same conflict of interest. Both had studied composition under influential composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. Both knew the tenets/ideas behind the Modern Classical school of thought – be abrasive, be abstract, be different. For Irmin, it was a trip to Andy Warhol’s studio in New York City that led him to discover there were other ways to make the “intellectual” popular. The sound of groups like The Velvet Underground and Sly and the Family Stone proved it. The performance art of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable showed it.

First, a short-lived avant-garde group formed with American flautist David Johnson and Holger Czukay gave way to something more substantial. Reconvening back in Cologne, together Holger and Irmin saw the potential to use rock music as a means to an end. They could rewire it and create a new European underground music, one that would be uniquely German.

“We were trying to find our own way,” said Liebezeit of CAN and fellow Krautrock bands like Neu! and Kraftwerk. “We thought like artists. Imagine a painter saying ‘I can’t suddenly paint like Andy Warhol or like Jackson Pollock, so I have to find something else, something original.’ It takes a while, but it is possible to find.” – Jaki to the BBC

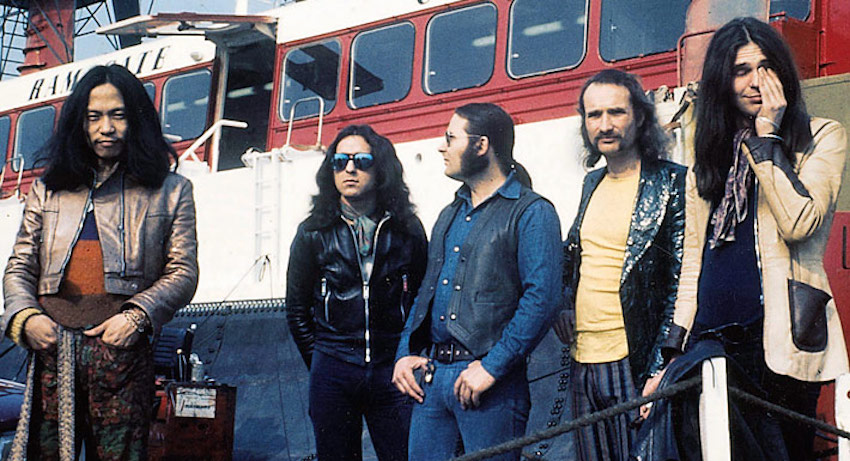

Joining forces with guitarist Michael Karoli (an ex-student of Holger) and Jaki, this new group would form the core of the band that would dub itself Inner Space. As their sound became less inner space and more kosmiche space, CAN was born. In CAN, Jaki had the freedom to make those repetitive, minimal, martial rhythms he had always wanted to create. Rather than run from the repetition, the rest of the group embraced the trance-inducing qualities it lent to their music.

Building up the band with unique, untrained vocalists like American sculptor Malcolm Mooney, and later Damo Suzuki (a Japanese singer they found busking the streets of Cologne), progressively CAN would introduce melodic ideas that saw Jaki’s metronomic style of playing as an asset. Serving as a counter to American psychedelic music, their own German kosmische rock would constrain song structures rather than sprawl sonically, drawing most of its psychic power by staying in the groove.

Forget long guitar solos and effects-laden sonic gimmicks: the music sounded exactly as recorded: improvisation sliced into looped perfection. The secret to CAN’s sound, and Jaki’s playing, was the band’s commitment to self-editing.

“With Can I was finally allowed to do what I wanted, repeating rhythms and grooves over and over again very consciously was a whole new thing at the time—even though this is an old idea: You find repetitive patterns in every culture of the world. In Europe during the ’60s this wasn’t understood at all. But the truth is simple: Without any repetition there is no groove.” – Jaki to Modern Drummer, March 2011.

Stretch Out Time

Recording lengthy improvised jams onto two-track tape gave the core group freedom to feel their way through a groove. Key to CAN’s success was Jaki discovering how to not do things that were expected. Rarely do you hear Jaki dramatically change the rhythm, and engage into pointless drum solos or fills. Subtlety has always been the key to Jaki’s drumming.

Creating one massive drum “loop,” Jaki would either add subtle accents or shift certain sections to vary the groove. These were the huge changes that allowed Irmin and Holger to overdub all sorts of interesting parts from other sections of a jam, and to slice or repeat certain rhythms to create something entirely unlike the original improvisation.

Using the same recording techniques pioneered by Teo Macero and Miles Davis to stretch out jazz music in America, CAN, were using it to compact their stretched-out jams in Cologne. When people talk about the huge influence of CAN on other artists like Roxy Music, Radiohead, Arcade Fire, and David Bowie (to name a precious few), it’s usually because of the way CAN rethought using the studio as instrument, and of drumming (or rhythm), as serving entirely an different purpose in music. Before samplers existed and drum machines became popular, CAN realized that all music could easily be arranged by rearranging it.

“The first time I heard Jaki Liebezeit’s playing with CAN,” says Wilco drummer Glenn Kotche, “I was hooked. You can tell instantly that there was so much going on with his playing just under the surface. His super-solid feel is readily apparent, but the way he uses dynamics and ghosting to enhance the groove is masterful. He also changes things up ever so slightly to perfectly enhance everything else that’s happening with the music. Sometimes he’ll just add one little beat displacement or loosen his hi-hats for one hit. It’s little things like that—which keep things evolving over what might seem like a static beat—that I think a lot of drummers could learn from. I definitely have.” – Modern Drummer, March 2011.

A GUIDE TO THE MUSIC OF JAKI LIEBEZEIT

1970 (SOUNDTRACKS)

Ignore Monster Movie, CAN’s debut. Zero hour starts here. Both a display of their initial influence by the American underground and their attempts to move beyond it, into future realms yet unheard, Soundtracks (a collection of songs created for German cinema) symbolizes how CAN started and how they wanted to continue. On the two tracks featuring the singing of CAN’s first vocalist Malcolm Mooney, you hear how much Jaki’s early drumming style was influenced by the Velvet Underground’s Moe Tucker. However, when you get to the meat of the album, the songs led by vocalist Damo Suzuki, you get to hear what would push them to be pioneers. Far more metronomic and propulsive, motorik (as heard in the music of Neu! and Kraftwerk) was just a stepping stone away.

1971-1972 (TAGO MAGO AND EGE BAMYASI)

CAN would never go as out there musically and as in here, rhythmically, as in the dual releases of Tago Mago and Ege Bamyasi. Tago Mago was CAN and Jaki at their most trance-inducing. On Tago Mago, you’d hear them devoting long stretches of time squeezing into every loping second of music as many interweaving melodic ideas as possible. Using a simple jazz kit, Jaki honed in almost entirely on the toms and snare, creating a heavy, percolating sound far from any English or American musical tradition.

Ege Bamyasi was the opposite. This was CAN at their most accessible. Compressing their sound into concise songs, stuffed with as many polyrhythmic grooves as possible. CAN never sounded as heavy – and as funky – as they would here. Endlessly sampled, Ege Bamyasi showed roots of many musical styles yet to be born.

1973-1977 (FUTURE DAYS)

The most surprising thing about CAN, and Jaki in particular, was the way their initial groove-driven period gave way to a more relaxed, almost ambient period where a lot of their playing became less dense and more atmospheric. This period was driven by rhythms there were more implied than explicit. On albums like Future Days, you’d find Jaki dampening his drums kit to contribute. In doing so, Jaki was able to stress the more percussive, melodic elements of his playing and the drum itself. His was an effort to blend into the background, in a way that better worked with the fascinating, new world music the rest of the group was trying to breach. Textural more than visceral, Jaki’s drumming would never sound as subtle as it does here:

When CAN lost lead singer Damo Suzuki, and Michael Karoli stepped up to lead vocal duties, Jaki, through albums like Soon Over Babaluma, Landed, and Flow Motion, stepped up with his most interesting takes on what a drummer can do. Again, emphasizing texture over the visceral, Jaki’s playing during this period would simply become more intricate, implied, and mesmerizing. Few sides of his drumming would be as hard to replicate by others as this one.

The late ’70s found Jaki rolling more overt funk, disco, reggae, and African influences into his drumming technique. By reshaping his style yet again, Jaki transformed what CAN could pull off musically. One doesn’t have to go far to see the fruits of his labor. Witness this set of songs, performed live, from Soon Over Babaluma and Saw Delight, for perfect examples of the band’s stylistic shift:

1978-PRESENT

It’s fitting that the most experimental and least understood of Jaki’s work would be found in his session work with other musicians. Gracing songs like Brian Eno’s “Backwater,” albums by Michael Rother, Eurythmics, and Joachim Witt with his quicksilver drumming technique, Jaki again displayed a shocking versatility that many rock dinosaurs simply couldn’t keep up with.

So, when placed with other hungry artists that had different roles for Jaki to play, he could still deliver fascinating new ideas that fit outside the drumming mainstream. Willing to integrate electronic triggers into his own drum setup, and using drum machines as accent devices, Jaki’s ability to remain cognizant of changing times allowed him to remain au courant and forward-thinking. Surprisingly malleable, this newfound arrangement would allow Jaki to easily contribute outstanding ideas to the work of artists like David Sylvian. Need proof? Check out this forgotten, futuristic contribution to this track from Jah Wobble, The Edge (yes, that Edge), and Holger Czukay.

Leave a Reply