What’s more surprising than the revival of the vinyl record market? The revival in people not knowing what a record player or turntable is, what the things on it do, or how they work — or that record players and turntables are, in fact, the same thing!

If you fit this description, don’t fret: we feel you. It’s easy to get bogged down in the details or unwanted tech-speak. Let’s avoid all that nonsense and get down to the essentials.

What’s a Turntable?

A turntable provides a surface on which you place a record with grooves that will be picked up by a needle, converted to a voltage by a cartridge and sent to an audio output that then in turn gets amplified through a speaker or another amplifying device (typically called a phono preamp) which then lets you hear the audio that was pressed on that record.

A record needs to rotate at a specific speed, or revolutions per minute, to accurately reproduce the recorded music. The shorter the record’s runtime, the smaller the diameter of the record, and the more revolutions per minute the record should be played at.

Records themselves come in a few sizes: 7-, 10- and 12-inch formats. Records also are “meant” to be played at specific speeds: 33, 45 or 78 revolutions per minute. The suggested RPM for a record usually coincides with a musical format it were made for: a single, EP (extended-play), or LP (long-play).

- 45 RPM: These records usually consist of a single track on each side of the disc. The “hit” would be on the A-side and the “deep cut,” aka what true fans would rather hear, would be on the B-side. Some experimental or punk bands could fit whole “albums” in one 45 rpm, 12-inch disc.

- 78 RPM: Congratulations! You’re the proud owner of old-timey music. This is the record format where you’ll find guys who made a deal with the devil, gals who’ve been wronged by said man, and Jazz guys providing a soundtrack to all of that by speeding through way too many notes in just under four minutes. Also heard in this format: songs about doggies in a window.

- 33 1/3 RPM: Usually a 12-inch disc. This disc consists of a whole album of tracks (or one really long track if you’re Jethro Tull). If you’re a macho-tough guy or gal, your favorite track is the first one. If you’re the sad/romantic type, usually the last track, on either side — “A” or “B” — is your jam. Records are pressed a certain way to promote this kind of album order. Likewise, “serious” artists who hate things like editing, or have a “vision,” might extend their album all the way to two or more discs. These are called double or triple LPs.

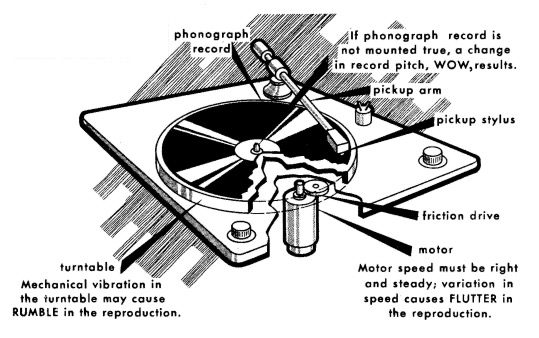

Turntable Anatomy 101

You don’t have to be an engineer or a graduate of your local technical trade school to appreciate what makes a turntable what it is. Your first turntable might not have the exact same quality components as Mr. Audiophile’s high-end Thorens deck, but rest assured: your turntable has nearly all the same components. So, what makes up a turntable?

- Stylus/Needle – This is a point, usually made up of a diamond needle, that rides the groove pressed onto a record. This is where we get the name “track.” Each track on a record has a start and end point where the needle starts its journey and then skips to the next groove, marking the start and end of a song.

Note: Some bands may play around with this feature and create a never-ending groove. Good news: you’ll usually find this trick at the end of a record side. - Cartridge – The cartridge is a small enclosure which produces a voltage when the stylus moves. In turn, that voltage gets transmitted to an electrical transducer that generates an audio signal.

- Tone Arm – This arm holds your cartridge and stylus in place as the record rotates. This arm also is used to guide which track you want to initiate playback — something called cueing. The better the tone arm, the more consistent the speed your record is spun. This means your tracks won’t sound unexpectedly slow at the beginning of a record and much faster near the end.

- Anti-Skate Weight/Control – Most inexpensive turntables won’t have this component. On better quality turntables, there is a counterweight attached to the tone arm that allows you to adjust the amount of friction between the stylus and record. This counterweight is adjustable to allow less or more horizontal movement by applying more vertical weight on the cartridge. Basically, this allows you to try to make the needle ride just in the middle of the groove by trying to resist the force spinning it into the center. Too much lateral movement to one side causes skipping. Too much pressure on the middle causes worn grooves that can damage your records. Used properly, your music sounds just right and your record has another bit of protection.

- Platter – This the surface your record is placed on. Its usually covered by a felt mat called a slipmat. This mat prevents scratches and also reduces vibrations. Some audiophiles replace stock, felt slipmats with cork or even leather versions to further reduce unwanted vibrations.

- Bearing – That protuberance holding your record in place as it spins is attached to a motor that spins the platter.

- Motor – There are two kinds of motors: belt-drive and direct-drive. Belt-driven motors use an elastic band to spin the platter, much like a pulley system spins the wheels of a bicycle. Typically, the motor of a belt-drive turntable is separated from the platter. Direct-drive motors are different in that they are attached to the platter. As they turn, the platter turns.

– What makes one better than the other? Usually, you’d want to go for belt-driven turntables if all you care about is playback. Generally, belt-drive turntables are quieter and transmit less noise/vibration to the platter. They also have the added benefit of being easy to service and switch bands as they get worn down with use. However, if you plan to use a turntable for DJing, sampling, or recording, my preference/suggestion would be for you to go for direct-drive turntables. These turntables can quickly rev up to speed and offer a consistent spin.

- Feet – Hardly ever seen but of immense importance, turntable feet are what allow you to properly level your “playing field” and further negate unwanted vibrations. The key to good record playback is always stability and quiet operation. A good set of feet allow you to adjust the height of a turntable’s corners according to the contours of your furniture or floor. Not everyone has a level floor or furniture, and not accounting for this can prevent your tone arm from properly steadying its cartridge ship, since it will want to creep to the side where its most inclined to go. Feet on high-end turntables are also made of damping material to add one more layer of noise protection.

- Plinth (Base) – This is the stage, or foundation on which all other parts reside. This base is also designed to remove most unwanted vibrations by isolating as many of the other components from it as possible. Generally, the heavier the base, the better the protection against vibrations that can transmit themselves to the needle or platter. However, modern (usually expensive) turntables have rigged up ingenious ways (be it through materials or design) to compensate for or negate unwanted vibration.

- RCA Output – The final key of the puzzle. RCA outputs are red and white phono jack connections that allow you to connect your turntable to an external speaker system or to a pre-amplification device. Most of the time, you’re given the option of using your turntable’s built-in phono preamp, or to bypass it altogether and use an external preamp. When you switch to the preamp output, you’re sending a line-level signal that another component like a speaker can amplify. When you switch to the phono output, you’re sending a much lower-level signal that you are going to send to another external device to amplify. If you’re serious about your music, normally, you’d forgo the preamp built in to your turntable and use an external phono preamp that can amplify that phono signal with far more clarity and less noise. This same phono preamp can also provide needed volume control. All these signals must go through a stage where they get amplified to a signal level that applies RIAA equalization which, in theory, reproduces the original audio as pressed onto the record.

Turntable Terminology You Should Know (But Would Rather Google)

Again, this is the section many, rightfully, should skip over. It’s everyone’s least favorite topic: specifications!

Manual vs. Automatic

Manual turntables consist of the vast majority of standalone turntables out there. These turntables require you to manually press play and move the tone arm to the record. If ever you’ve ran to turn off the repetitive whooshing sound coming out of your speaker, it’s most likely that you forgot to return your tone arm to its holder when the album finished, and that you’re the proud owner of a manual turntable. Automatic turntables automatically do the work of moving and lowering/raising the tone arm to your record. They also return back to their holder when the record side is over. Some (linear-tracking turntables to be precise) can actually seek back and forth like modern CD players/audio files. Sadly, those were lost in the great Betamax war of the past. Most audiophiles, though, swear by manual turntables because there is one less component to fret introducing noise/vibrations to the record. Most normal people accept the trade-off of automatic turntables because it frees them to do other things like wash dishes or take a nap.

Signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio

If everything was as straightforward as this phrase is, we’d be in a better place. Signal-to-noise ratio, or S/N for short, is the measurement of how much background noise (in decibels) you’d expect to hear introduced onto the musical signal. If you excelled at basic arithmetic, you’d know that the number you want to see higher in the equation is the signal part. Do the math, and buy a turntable with a favorable dividend (another cool math term!)

Wow and Flutter

Obviously, this specifies how much wow and flutter a turntable has. Before you run and start thinking there are wondrous butterflies in your turntable, step back and come to the cold, hard realization that this means something else. Wow and flutter is the measurement of frequency fluctuations, up and down. In the olden days, before flutter existed, wow was the name given to how much pitch variation could arise when a record wasn’t pressed completely flat and on-center. The more warped the disc, the higher the pitch variation.

Somewhere down the line, in our younger, hipper days, wow was used for exclaiming things that were cool, so engineers had to introduce another phrase for clarity. This phrase: flutter (used by our friends the birds) was repurposed: to denote media that had a higher rate of wow. So, sticking them two together gave you an idea of how much low and high pitch variation you could find on a turntable during playback. I know, why not just call this measurement warble or wobble? Thank filmmakers for that. They use wobble and jitter to denote how improperly balanced an image is, which in turn they sometimes define as flagwaving, which is their ridiculous name for the visual version of wow and flutter.

Starting Torque

We all love cars, right? Torque sounds cool, like wow-minus-flutter cool. It’s a cool measurement as well. Basically, it means how much energy/power the motor uses to rev up an engine from standstill. Generally, if you have a sweet muscle car, you want as much torque as possible. You have the “need for speed,” like noted philosopher Vin Diesel says. The more torque, the faster your car can go forward, cross the finish line, get the girl/guy, then do some sick donuts. This kind of torque isn’t different for turntables. The better the torque measurement, the faster your record gets up to speed, and starts to play the track (with less noticeable audible speed up) when you drop the needle. So, rather than hear what sounds like Bob Dylan swallowing a marble and yawning, you hear Dylan instantly singing “Lay Lady Lay.”

Pitch Variation

Everyone’s favorite. This is the control that unruly kids, curious cats, and nosey partners love to play with. Pitch controls on turntables allow you to adjust in increments the speed a turntable can change from a set RPM. Full chipmunk voice? Easy: set the fader or button up to the plus region, and make the record spin faster than normal. Fan of the California Raisins? Well, you can set that control all the way down in the negative region and watch the record slowly turn to a crawl. There are ways to make this control sound musical, but we tend to leave that to the “professionals.”