Talking to Victor Wooten, you get the impression he never puts his bass away for too long. From his childhood gig performing in a band with his four brothers on through the highly anticipated Bela Fleck and the Flecktones reunion tour starting this summer, Wooten has earned his place as one of the first names spoken when people discuss the world’s best bassists. But talking to Victor also shows that he didn’t get here solely through rote, isolated practicing, but by maintaining his love of playing and letting his experiences inform his groove.

Victor’s camp, Wooten Woods Center for Music and Nature, embodies these priorities, giving its students not only world-class music education, but activities like yoga, tai chi, and getting out to hike and experience the landscape. We got a chance to talk with Victor about all of the above, plus his relationship with Hartke, getting to play with his idols, and much more.

Victor Wooten’s first Hofner bass seen on the cover of What Did He Say?

zZounds: Do you remember the first gear you started playing on?

Victor Wooten: My first bass was a copy of a Paul McCartney Hofner, but it was a Univox. If you take a look at my record called What Did He Say?, there’s a picture of me standing in the woods with a bass on my back. That was my first bass. I don’t remember my first amp but I do remember that in my early years I know we had Plush Amps. I know I had a bass rig and I think Reggie had a Plush amp.

I still have the Univox. My second bass was an Alembic Series 1. I was such a Stanley Clarke fan and that bass is still too large for me; it’s a huge instrument. When I got that bass, not long after Reggie helped me pull the frets out of it, because that was at the midst of the emergence of Jaco Pastorius in the mid ’70s.

zZounds: Through your career, you’ve gotten the chance to play with your idols, people like Stanley Clarke and Boosty Collins. Any valuable lessons you learned from playing with those guys?

Victor Wooten: Everybody has different methods. People like Stanley, Bootsy, Marcus — these are my childhood heroes. Especially Stanley. I’ve always heard from people, you have to be careful when you meet your heroes; you might be disappointed. I haven’t been disappointed yet. And it’s not that everyone’s perfect, everyone’s human. And I understand that going in, but to be that close to one of my heroes is amazing. And really the surprisingly hard part about it was being treated as an equal to them. When I’m with Bootsy or Stanley or Marcus, the general public looks at me as their equal, but in my mind, I met Stanley Clarke when I was nine years old, so whenever I’m with Stanley I feel nine.

When I’m with Bootsy or Stanley or Marcus, the general public looks at me as their equal, but in my mind, I met Stanley Clarke when I was nine years old, so whenever I’m with Stanley I feel nine.

Working in the studio [with Stanley and Marcus,] there was one song we were working on and Stanley had to take a solo. He was having a little bit of difficulty figuring out how to play over it. And so one of the cool things was to see Stanley struggle at something. I was like wow, he’s human, that’s cool. But it was neat to see him put the bass down and go over to the piano to figure it out. And that’s a skill that I don’t really have. And I literally was just sitting down at my piano to try and get better at that. Because the greatest players that I know, like Stanley, Marcus, Jaco, Steve Bailey — they all play piano. And I don’t, and so I find out that the guys that hear music the best and have the best harmony all play piano, so it was neat to see Stanley work it out that way.

Steve Bailey is an amazing businessperson; he has an amazingly sharp mind. And from our very first project — Bass Extremes back in the ’90s — I learned a whole lot about business, sitting with him as he negotiated that deal with this company that didn’t believe in us; didn’t believe that two bass players could make an interesting project. And so Steve had to convince them. And it was at a time that there were no sales on the internet and so in the contract the company wanted to give us only 50 percent of internet sales. And Steve was a forward thinker and was saying no, don’t cut us in half there and the company is telling us, ‘internet is only one percent of our sales.’ And we were thinking OK, well then if it’s only one percent, you should be giving us double, not half. That’s Steve’s mind and he was right. He was a forward thinker, he could see into the future and he stuck with it. And in the end that became the biggest bass product and one of the biggest music products that this company had ever put out.

zZounds: I really like your arrangement of ‘Overjoyed’ by Stevie Wonder [from the album A Show of Hands] I was curious, when you listen to a pop song like that, what triggers do you hear that make you think you want to play that, and what do you think needs to be there in the song for it to sound good on bass?

Victor Wooten: Well first, any song by Stevie Wonder is a masterpiece. I mean, you could take any song by Stevie. Stevie to me is a true genius. We talk about jazz musicians and their harmony and skill, but in my mind there’s no one like Stevie. Because Stevie can take a complicated song and disguise its complexity, you don’t know that it’s complicated. Like Overjoyed — anyone can sing it. He repeats the first melody three times, then he resolves it. Beautiful. Then he does it again — three times, then he resolves this one up. Perfect match. It’s so simple that anyone can sing it and so the song sounds simple. Until you go to learn it. And then you realize, ‘wow, these chords are deep. I don’t know how he’s doing this, he’s modulating in some way and then making it right back.’ So I’m saying that not to say that’s what drew me to the song; it’s just a beautiful song. The fact that it was Stevie Wonder just made me want to learn it.

But when I’m learning a song like that, I start with the bass line and melody. And even more accurate, the bass notes and the melody. So like in the first verse of that song. I’ll play that with my right hand and then figure out what is the bass note underneath it? And then for that particular song I did it in E Major, so I played it in E. And now that I have the melody note and the bass note, I just figure out what is it possible for me to play in between those? How much more of the chord can I possibly get? And if the chord is bigger than my four strings will allow, then I have to have movement in the chord to go from one note of the chord to the next note of the chord, so that your ear registers more than four notes even though I’m not playing them all at the same time. And then I just go through the song little by little from that. But overall, I know that I have to capture the feel of the song and not just the notes. The songs that we play create emotion and feeling and we have to capture that and that’s a thing that I hear some people forgetting to do because they’re just learning the technique and the notes and maybe forgetting some of the feel.

zZounds: ‘Norwegian Wood’ [from the album What Did He Say?] is another excellent arrangement you do of a classic song. There’s some cool reharmonization you do on that. Is that due to the limitations you have on the bass — only two hands — or do you think more harmonically separate from the bass?

Victor Wooten: You know it’s all of the above. I would love to be able to say that I’m always really clever like that and that good of a musician, but sometimes it comes as an accident. It could be that I can’t reach a note or I thought it was a G but I played an F and I thought ‘oh the F sounds good!’ Sometimes I hear it. Because I’ve listened to a lot of jazz and classical, I hear that stuff sometimes. But I also want, as well as to do justice to the song, I want to add myself to it. And with a song like Norwegian Wood, it’s only going between an A and B section. So why not do something different with it the second time or the third time it gets to one of the sections? Can we change it up a little bit?

I was living in Nashville and I got contacted by a gentleman asking me to be part of a John Lennon tribute show. And I said ‘sure, I’d be honored, but I don’t know any John Lennon songs, can you send me a recording?’ I didn’t grow up listening to the Beatles, because the Beatles were happening at the same time as Motown. We were listening to Motown and Sly Stone and James Brown and stuff like that. He sent me a tape with a bunch of John Lennon songs — I realized I knew every one of them. I had heard every one of them, I just had no idea who it was. I had never paid attention to it, but of course I had heard it. And I chose ‘Norwegian Wood’ — it had just grabbed me for some reason. And the day before the concert, I came up with that arrangement of it and I improvised that arrangement for the show that night and then fell in love with the song so much I was like ‘I need to record this.’ So on the recording I can add things until it sounds perfect. So I fixed it up, dressed it up a little bit, colored it a little bit, probably added some more reharmonization for the recording, but that was how the song came to me.

Perhaps the bass Victor Wooten is most associated with, — the Fodera Yin Yang Standard. (Credit: bassgear.co.uk)

zZounds: In addition to playing bass, you started on fiddle early in your musical career. Can you tell us about that?

Victor Wooten: I started playing with my brothers I guess a lot around 1970 or so. In ’73 I think, we moved to Virginia and then were playing there and then in ’76, in the sixth grade, I joined the orchestra in my middle school. I started playing cello. So that’s where I started learning how to read music and how to bow. But right around ’81, I’m in the 11th grade, my brother Roy calls me and says ‘hey I’ve got you a job playing fiddle if you want it. Do you think you can do it?’ I’d never played fiddle in my life but I said yeah!

Without going into this story, there was a time, through a bad record deal, our brothers weren’t playing together as a band as much and we were kind of all spread out and had to find other work. We were all working at an amusement park in Virginia called Busch Gardens. And I was actually too young to be in what they call the live entertainment department, so my brother Reggie had gotten the bass part in the live country show, and at the last minute they needed a fiddle player, so Roy called and asked if I could do it. So I went to my high school, borrowed a violin and started learning classic fiddle songs. So that’s when I started playing fiddle — it was actually a long time after I started playing bass with the band.

zZounds: Did you find that any fiddle techniques crossed over to bass or vice-versa?

Victor Wooten: Well, probably a little bit of both, but more so it was just a style of music. Learning bluegrass was a new style that actually led me to meet Bela Fleck. So it was that style of music that influenced me a lot more. But playing cello and later violin, I had always loved the sound of the bow on the strings. And so now I even have a bass that I can bow.

zZounds: Can you tell us a little about how you met Bela and came to be in his band?

Victor Wooten: In ’87 I went to Nashville, Tennessee to visit a guy I had met in Busch Gardens in 1983, a guy named Kurt Story. He was known as the fiddling bear because he’s a big guy and an amazing fiddle player. He took me under his wing and taught me a lot. At Busch Gardens, they always had two companies doing the same shows so they could perform every day. So Kurt was in one company, I was in the other. He was a real fiddle player, I was an imposter. But in ’87 I finally went to Nashville to visit him. And Kurt, being born and raised in Nashville, knows everybody. And so he introduced me to Bela and a bunch of other people. So my first visit to Nashville in ’87, I didn’t actually physically get to meet Bela, but Kurt called him and put us on the phone together. And Kurt had been telling all of these people — Bela and Sam Bush and all these top bluegrass players, Mark O’Connor, Edgar Meyer — he had been telling these guys about my brothers and me, because we had this black family at Busch Gardens playing bluegrass and country music, so it was kind of rare. So they knew who we were but we had never met.

So I ended up talking with Bela on the phone on that visit and I played some bass over the phone for him and a lot of my thumb technique using my right thumb and first two fingers is very similar to Earl Scruggs’ style of banjo playing, which is how Bela plays. So Bela says ‘wow, it sounds like a bass banjo.’ And that was the start. So later that year or early the next year I came back to Nashville to play with a woman for a month, and during that month was when Bela and I really hung out and jammed together and then he told me about this television show he’d been asked to do and wanted to put a band together for it and asked me if I’d play bass. I said sure and that was either in ’87 or ’88, I can’t remember right now, but that was the beginning of Bela Fleck and the Flecktones.

zZounds: What was the name of the show?

Victor Wooten: It was a show in Louisville, Kentucky called The Lonesome Pine Specials. And it was an incredible series, there was a guy who would just contact musicians and do an hour television show on them. He contacted me one time and he also contacted Edgar Meyer. And he asked us both, he said ‘I want to do a bass special featuring you two, and who would you like to play with?’ And Edgar said Ray Brown and I said Stanley Clarke. So he contacted Ray and Stanley. Ray Brown was available, Stanley wasn’t. So instead of getting a replacement for Stanley, we decided to do a trio. So it was an hourlong special featuring Ray Brown, Edgar Meyer and myself.

zZounds: I was reading on your website a story about how you would go out on your and try out different rigs every night and eventually you settled on the LH1000. Can you tell me about the tryout process and what stood out about Hartke to you?

Victor Wooten: Absolutely. I used Ampeg for many years, actually Steve Bailey and I met endorsing a new company called ADA in the early ’90s, and then we chose to go to Ampeg together. And we both used Ampeg for many many years, and I still love it but I also like change. And after a decade or so of using Ampeg, I just decided I wanted to see what else was out there. So I gave Ampeg almost a year notice that I was going to finish out this year and then I was gonna see what was out there.

So I took a year just to try stuff. And it was at the time I was touring with my own band and I was using another bass player, my good friend Anthony Wellington. And so I contacted a bunch of bass companies to let them know I’m searching. And fortunately my name meant something now to these companies, and these people sent me rigs to try out. At one point on tour, we literally had 25 different bass cabinets.

zZounds: I’m sure your roadies loved that.

Victor Wooten: They actually did! Because it wasn’t like we brought them all out — they were in a trailer, and we asked them to just set up whichever ones they wanted each night, just surprise us. And somewhere we took a picture with all of them in an alley. But I tried a bunch of stuff and then I took my favorites and contacted the companies and met with the companies, because for me it starts with the sound, but then it boils down to who are the people making the cabinets?

So there are a few things that I’m looking for in a company: one being the sound. I also want to know who’s making it, I want them to like me, I want to like them. But the company also has to be big enough to support me. Not to sound egotistical, but I travel a lot — like I just came from Mexico — is the rig gonna be there in Mexico? And I wanted them to support clinics as well as my camps, because I just started doing my camps in 2000. And in the end, Hartke won, hands down. They had just come out with their HyDrive speakers, and I was gonna be one of the first to introduce these new speakers, half aluminum and half paper, and then their cool LH1000, a 1,000-watt bass head.So even before I was endorsing them, they provided gear for me on the first SMV tour with Stanley and Marcus. And so literally Stanley and Marcus were traveling with speakers and I travelled with a bass and a suitcase and we’d show up in Istanbul, Turkey and my rig would be there. And they’d say man, these guys are cool. So Hartke won me over easily. We like each other, still like each other and that’s what I’m still using.

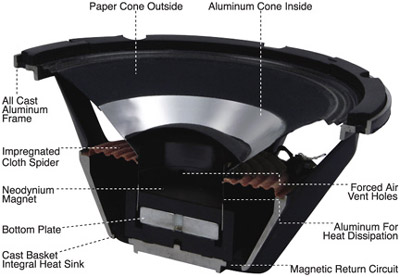

Hartke’s HyDrive speaker

zZounds: What do you feel are the tonal benefits of the paper and aluminum hybrid design of the HyDrive speaker?

Victor Wooten: Well it’s all choices. Like clothing, you might like Nike, I like Adidas. You’ve got to do what makes you feel comfortable. But the aluminum is a bright speaker that can really cut through in the rock world where you’re playing with a pick and that kind of thing. The paper cone is a warmer tone where the HyDrive gives you a little bit of both. I’m a very percussive player. So I need a speaker that’s gonna respond quickly and give me the attack that I need. I’m not usually playing a soul/R&B gig like for Anita Baker or Whitney Houston where I need fat, long notes. I need the percussiveness. And these speakers do that easily. It’s a good sound and versatile — it gives me the opportunity to play in different styles using the same rig.

Hartke KB12 Kickback

zZounds: Have you tried out the new Hartke Kickback amps? What do you think of them?

Victor Wooten: I think one of these Kickbacks is a 500-watt little combo, and that’s a lot of wattage for a combo; it’s pretty amazing. Again there are choices there. You can have a 25-watt combo or up to a 500-watt combo. So there’s a little amp that can be a practice amp but then you can take it up to the stage if you want. I think they’re good little amps. I use them at my camps, and I’ve got a couple of them at my house.

zZounds: What do you feel like Hartke personifies as a company and what is their place within the bass world?

Victor Wooten: Well, one of the things I like about them is they make gear that’s affordable. I like gear that people can go out and purchase. And the HyDrive speakers are surprisingly light also. So with this Hartke gear you’re not gonna break your bank or your back. But overall, it’s really the people behind the company. The president of the company, Jack Knight is a wonderful bassist and he’s honest and just a really good guy. In the end, I know that I’m not only endorsing the company, I’m endorsing the people. I want to know who the people are and I want them to know who I am. They’ve been very good to me and from what I hear they’re good to their customers. Fixing problems that arise. So far I’ve only heard good things when I visit stores representing Hartke. And plus they are partnered with Samson, so with Hartke comes great microphones and speakers and different things like that.

zZounds: Tell me a little about your love of nature and how your Wooten Woods Camp brings it all together with music.

Victor Wooten: Wooten Woods is our location. It’s a 150-acre retreat center just west of Nashville, Tennessee. Back in the early ’90s I started studying with Tom Brown Jr. who’s a naturalist in New Jersey of all places. But he’s been teaching and has dedicated his whole life to bringing people back to the earth. And when I started studying with him I realized what he called nature, I was calling music. I said this guy’s teaching music, whether he knows it or not, he’s teaching music. And I felt that this is the way music should be taught. Not lock yourself in a room and practice all day. And so it really opened up my mind to our approaches to music and our goals in music. We want to play music and really want to do it naturally. When you’re doing this interview, you don’t want to be focused and concentrating so hard or sweating, we want this conversation to just be natural. And I realized everything we do is that way: we want to be natural, whether it’s driving, walking, talking or anything.

And I realized that with all this practicing on my instrument, I’m really trying to be like nature. And then I wondered, ‘why should I lock myself away from nature in order to do it?’ Why are we told to lock ourselves in a room and the more hours we spend in that woodshed, the more natural we’ll become? that’s just as opposite as it can be. If you think about talking, we’re natural because of the process of not being locked in a room. It’s why you have your own voice and you never had to work on it, it was there and natural from the beginning. So I started using a lot of [Tom’s] exercises and applying them directly to music. And it was then that things started to open up in my mind and in my ability. I started getting the idea in the mid ’90s to share this with people. And speaking of Steve Bailey, he was the first one. He was the guy I started experimenting on, because that was right at the heart of me taking classes with Tom. I took classes with Tom for 10 years.

Victor teaches a bass lesson at Wooten Woods

At the camp we do a lot of music, but I always have a nature instructor there that will get the students outdoors and paying attention to it: literally breathing, walking, seeing and doing different things outdoors and then when they bring that back to their instrument, without having to tell the people anything, they go ‘wow;’ the students get it. And they understand it. And of course we do all the normal things too, we sit down in the room and we practice. But my method is practice a little, play a lot. And most people reverse it. Most people practice a lot and play a little, which is an unnatural process. And so the other thing too is that because our camp is pretty much all-inclusive and we’re usually there 24/7 through the entirety of the course, to play music 100% of the time I think would be detrimental to your ability. you have to get away from it. So when we get away, we instructors have chosen other things to do that relate to music whether you see it or not, that are beneficial to your lives. So in the morning we might wake up and do yoga, or tai chi, or other listening or blindfolded exercises that help wake up other senses in your body. Basically, we’re giving you experiences to play about. Music is communication and if you lock yourself in a room and that’s all you do, you have nothing to communicate except that room and maybe some exercises that you play. But if you have experiences in your life, now you have something to play about. And at our camps, we try to provide those experiences in the best and most natural way. And it works.

Music is communication and if you lock yourself in a room and that’s all you do, you have nothing to communicate except that room and maybe some exercises that you play. But if you have experiences in your life, now you have something to play about.

zZounds: Wow, I want to sign up for that!

Victor snaps a selfie at the creek. (Credit: Wooten Woods Facebook page)

Victor Wooten: And you should; you should come visit us sometime. It’s really different, but it literally changes peoples’ lives for the better. There’s a great store near Philly called bass specialties run by a guy named Glenn Marrazzo. Glenn came to our camp as a student and he was running a catering business. And he just got so inspired by his experiences at our camp that he sold his catering business to his brother and opened up a bass shop. Another female at our very first camp ended up being Beyonce’s bass player for six or seven years, Divinity. Another girl from our first camp, Alana Rocklin is now the bassist for Sound Tribe Sector 9. Another guy, Brandon Brown, who was at our first or second camp, is now the bassist for the Jacksons, he’s rehearsing with Fergie. Another guy at our first camp, after that camp moved to Nashville and now he’s playing as the bassist for Luke Bryan. And I’m not taking credit for anyone, but it’s nice to inspire people and see them prosper and grow. And these four people that I mentioned, they get it. Our camp is different than any other that I’ve seen. I’m not saying it’s better, I’m saying it’s different and that it does work.

zZounds: How many sessions do you do per year?

Victor Wooten: We usually do camps March through October, we do something every month. This year is slightly different. We’re kind of in a rebuilding phase: putting our not-for-profit status to work, reorganizing and revitalizing our board and raising money. We’ve been just existing off of tuitions and making the camps as inexpensive as possible for students. So this year is a shorter year, we’re only doing camps in July and August so that we can put a lot of our focus in getting the structure of the not-for-profit behind the scenes in order. so this year is a shorter year and next year, which will be our 18th year, we’ll come back with a lot of new programs, new energy and new camps. Basically what I’m trying to do is to make the organization bigger than me. I’m at every camp, 24/7. So if I’m on tour, that means people aren’t there learning when they should be. I want people to be there learning and growing whether I’m there or not. So one of the goals is to start training instructors on our process, our method, and our ideas so that people could be coming and learning there whether I’m there or not. So that’s gonna take a lot more organization, more finances, we’ll need more cabins for our instructors and students, more practice rooms and things like that. So we’re getting all that structure together now.

I’ve got four kids — one of them is in her first year of college, and I’ve been touring her whole life. I’ve got three more kids and I don’t want to tour their whole lives. So my idea is to get the camp to a place where I can go there and make that my daily job and tour less.

Leave a Reply