The Musical Almanac is an ongoing series highlighting musical styles or genres from around the world. Our future destination is to get to the powerfully sublime Nouvelle Chanson music of France. But, first, we have to explain how we’ll get there. Today we take one step back and discover its humble beginnings. Stay tuned for the next part in this special series.

Somewhere, in the lyrics of Parisian Jacques Dutronc’s “L’éthylique” lay signposts pointing to exactly what Nouvelle Chanson is. Translated cleanly from French, it means the “New Song.” Taken literally, it’s a simple phrase, but what exactly does it mean? On the web, there’s a whole Wikipedia entry dedicated to a decidedly misguided take on what Nouvelle Chanson is. If a new song existed, there had to be some older song, or Chanson that it was replacing. This is the time we’re exploring — when France introduced an entirely new kind of music.

Jacques Dutronc’s “L’éthylique“

Before the Great World Wars, in the dens of expression — in the saloons and cabarets of France — artists like Edith Piaf, Lucien Boyer, and Marie-Louise Damien (to name a precious few) were transforming the idea of what exactly it was to be a French performer. But lets go back just a bit further. Before them, existed only songwriters, composers, and song interpreters. The idea of a singer-songwriter didn’t exist as we know it. If you were on any stage then, what little currency you had, was beholden to someone else’s guiding hand.

Follow the Lieder

It all started so promisingly. Released in 1784, “Plaisir D’Amour” by Jean-Paul-Égide Martini set a course that would guide many ships thereafter. Tasking himself with bringing the theatricality of a concert hall to the more pastoral French Folk style, out from his headspace came this luxurious ode to love. Eking out a certain French musical quality that hadn’t been so pronounced to the world, it became the first true French pop song. Some of you may even hear its influence on one infamous king’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love.”

What could have been a banner movement swiftly became someone else’s raison d’etre. Before the arrival of the gramophone, Lieder, songs based on romantic German poems translated into French and set to classical music, were dominating the French music scene. It was in the saloons of the mid-1800s, that early French performers were tasked with marrying poetry with music. This era, dominated by the influence of foreign composers like Louis Neidermeyer, Johannes Brahms, and Robert Schumann, transformed whatever musical meter the French language had into one devoted to the creation of the most classic of French cliches: Romanticism.

Franz Schubert’s “An Die Musik” interpreted by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

Polish-born, French-naturalized, Frederic Chopin started to show a different path forward. Through mere improvisation, played in shorter musical bars, he managed to introduce an emblem others would put there stamp with in France. Imagine an Opera without the scenery, story, or orchestration. Short songs stuffed with as many over-emoting, sung vocalizations by over-expressive performers accompanying overly complex solo arrangements…that’s what ruled the day. This, however, could only continue on for so long:

What good is May’s sweet loveliness?

You were my beam of vernal sun!

Light of my night, come, smile at me

in death just one more time.

- From Franz Schubertz’s “Der Vollmond strahlt auf Bergeshöhn”

If that era had been dominated by the stylings of Chopin, Listz, and Schubert, a new century filled with new ideals and ideas would surely force France to look inward? The Franco-Prussian War had planted seeds of some necessary distance from Germanic ideas, but something else had to occur for this change to occur. Forget the rise of the cabaret, and the fall of the orchestra: total war would change French music.

The End of a Century

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt (1907)

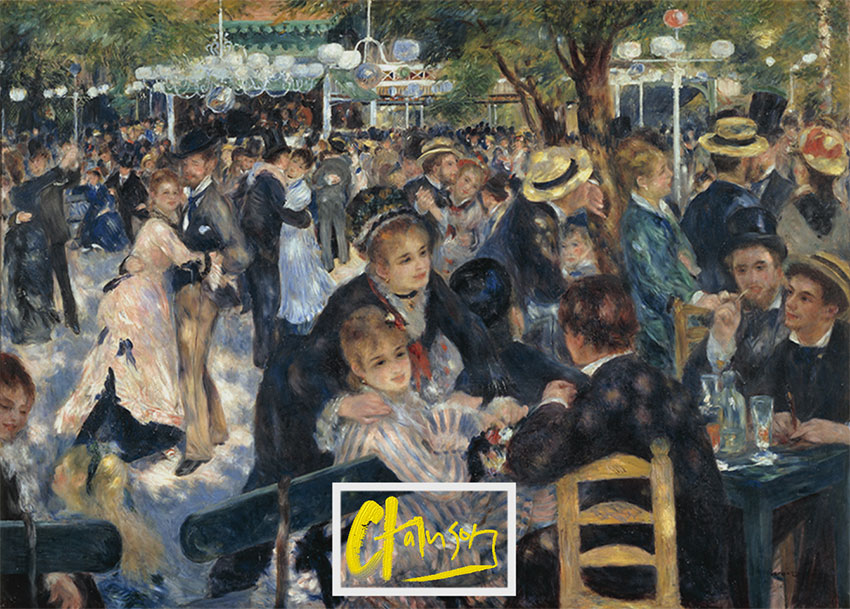

The traumatic experiences of World War I and II brought into light certain tensions France had been disguising. When France started to reintroduce itself to the world, during the Belle Epoque (1871-1914), it projected back an overwhelming spirit of beauty, peace, and prosperity through its own culture. Where Germans could only speak about love, France wanted to go beyond merely expressing it. It’s hard to encapsulate how this philosophy influenced its music, but Art Nouveau depicted a certain aesthetic that was infiltrating every aspect of society. Laissez-faire, for once, had taken root.

Now, you could show the beauty of something, but in doing so you had to remove certain adornments that over-embellished a mood. Everything artistic had to have a certain dimensionality to it that had to convey the exact feeling a piece was aiming for. It’s this elaborate, organic softness you see in the paintings of Renoir and Gaugin. In music, you heard it in the waltzes and operettas. Such influence made this era of music overly-intricate in style, removed of all irregular or dissonant edges.

Chopin’s Nocturne: Op. 27 No. 2 in D-Flat Major (performed by Arthur Rubinstein)

Realist Songs

As the “Decadent” era that Rimbaud and Verlaine wrote about gave way to some truly freeform lyricism, and Art Nouveau gave way to a new time and aesthetics, Impressionism and Expressionism, musicians were having a hard time trying to convey exactly how much the world had drastically changed. The indescribable, and frankly, unimaginable things that many would experience during World War I and II forced the French to confront humanity in ways that hadn’t existed before. This exposed limits to the last remnants of Salon Music — it’s something the peaking modern minimalism of French composers Satie and Debussy acknowledged. Technology was laying bare the gauche sentimentality of classical Romance. If music would exist in this era, there had to be space for in-between feelings and ideas to exist.

Claude Debussy’s “La Cathédrale Engloutie: Profondément calme” (performed by Nelson Freire)

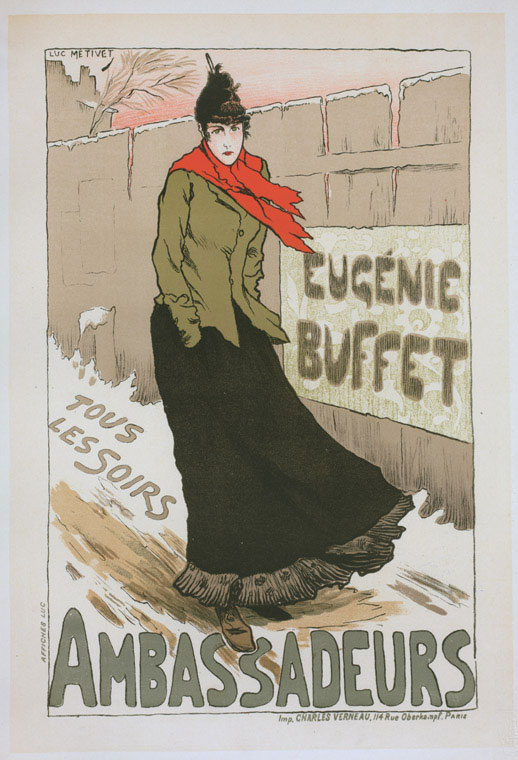

Back then they were called Chanson Realiste or Realist songs. These were songs dealing with topics many had considered taboo to sing about or not worthy of pondering. When Edith Piaf or Eugénie Buffet sang about brothels, grieving mothers and cheap love, it was truly something alarming. When Leo Ferre set the searing poetry of Baudelaire and Louis Aragon to music, outside of France many were struggling to understand what exactly he was singing about. They were singing exactly about the people that Belle Epoque forgot.

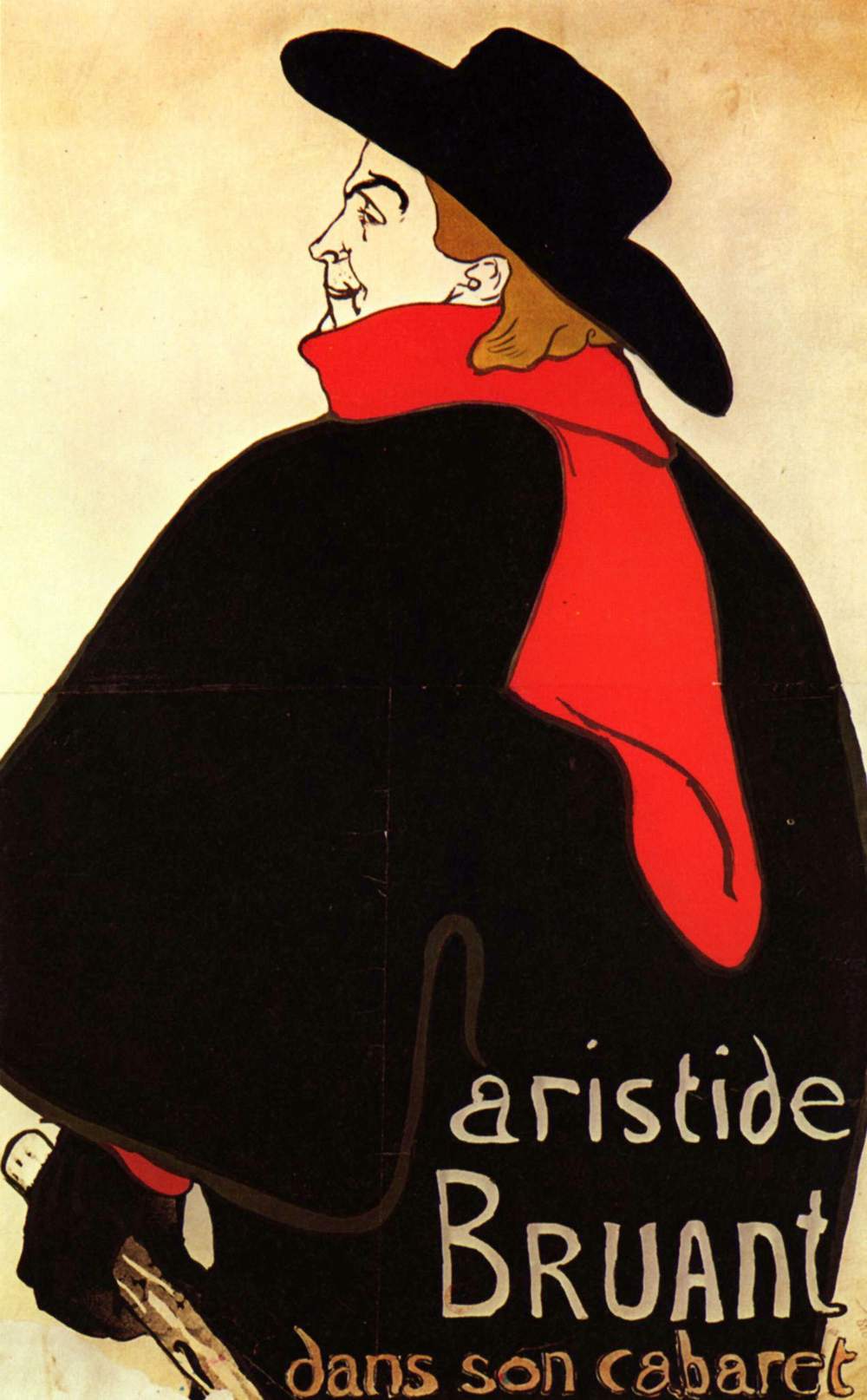

Aristide Bruant by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1892)

Aristide Bruant had given them all a head start by providing them an identity to exhaust. Don a red scarf, dress in black, apply some white face makeup and you’re a starkly-lit nightclub away from becoming a Chanson star. Rather than try to aspire for the higher class, you aspired to live like the downtrodden, even if you in fact came from a higher class. These self-christened Bohemians featured the types of musicians who began to use the tools of the forgotten downtrodden dance halls and cabarets — performance and attraction — to rejoin other artists into this newly arriving, modern world of music.

Looking for fortune,

Around the Black Cat,

In the moon light,

In Montmartre!

Looking for fortune;

Around the Black Cat,

In the moon light,

In Montmartre, at night.

- Excerpt from Aristide Truant’s “Le Chat Noir”

Their songs were deliberately arresting. Everything, from the achingly melancholic delivery to the thoroughly impassioned gruffness displayed in stage performances worked to project a certain intense, melancholic image. Once again, it was OK for the music to gain a certain embellishment and for songs to challenge audiences in ways they hadn’t been before.

Eugenie Buffet by Lucien Metivet (1896)

Promenade in Blue

Entrance to Le Chat Noir

The cabaret was the center for this new kind of music, Chanson, and its arrival marked a pronounced change. Rodolphe Salis’ “Le Chat Noir,” based in the Montmartre district of Paris, arguably the first truly modern nightclub, became the it place nurturing all sorts of talents and ailments. What began as a place for young malcontent radicals, Les Hydropathes, to espouse philosophy and trade water for wine, slowly began to offer something altogether new. It all began by Rodolphe hiring and stationing a guard to keep out all sorts of types not conducive to this environment — notably priests and members of the military. In his place, only a certain kind of person could enter, one far more progressive.

This exclusivity, which made it a mecca for writers, dancers, musicians, artists, and rabble rousers. What transformed it into a dynamo was an open stage. At Le Chat Noir, anyone could jump up, strike up a song, and swiftly hear a sound critique of their performance. What better way to cultivate and nurture a scene, if not among a jury of your peers? Among peers like Claude Debussy, Paul Verlaine, and Maurice Rollinat you could be risqué, you could be camp, you could create something uniquely yours…at Le Chat Noir. Poets encouraging lyricists, vocalists inspiring composers, artists informing culture. With time, singers and musicians like Aristide Bruant, Théodore Botrel, Yvette Guilbert, were creating a captivating stage presence that went beyond attracting the intellectual…they were drawing the bourgeoisie in.

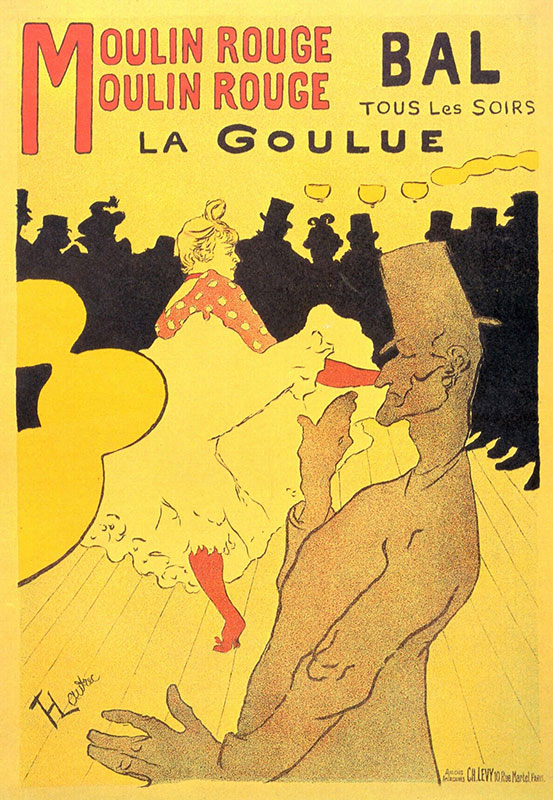

Jane Avril at Le Moulin Rouge by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

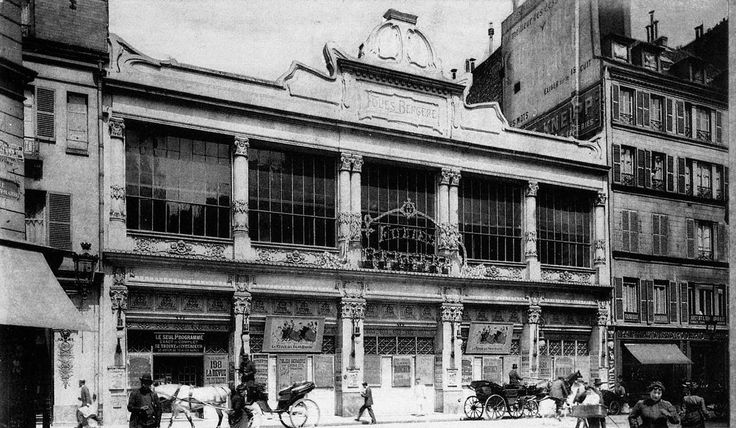

As Jane Avril’s kicks punctuated newer, far more luxurious and fully vested cabarets like Le Moulin Rouge, audiences were demanding more. More skin, more emotion, more everything. During the Golden Twenties, Folies Bergère cemented the change. Skin was in.

- Folies Bergere – Then

- Folies Bergere – Now

Folies Bergère, a converted opera house, began programming as a music hall, but slowly evolved into something else altogether. It developed a new focus: women. Guided by the hand of music director Paul Derval, they’d go for titillation. Sparing no expense to cloth the stage, they set the scene for performers like Josephine Baker and Edith Piaf to bare nearly all. Rather than be part of the show, through their performances, they did something amazing. Now, women were at the vanguard, honing modern French culture.

“J’ai Deux Amour” by Josephine Baker

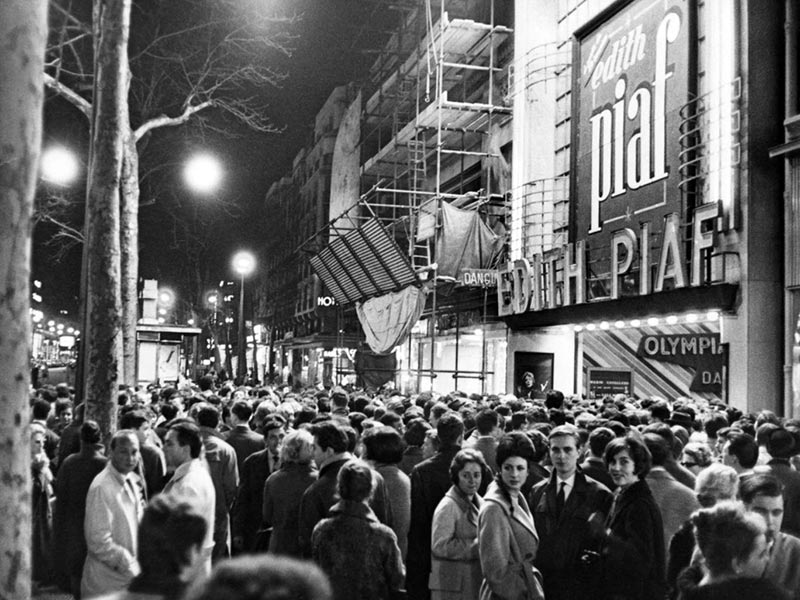

When Paris music hall, L’Olympia, reopened after World War II, Piaf songs soundtracked a much different audience. This was an audience struggling to come to terms with the end of the good times. Hearing songs dealing with race, inequality, and modern love, to tunes played by in-house pianist Pierre Boulez signified the spirit of the times. Songs had grown knowingly darker and performances far more severe.

This kind of music, recorded before anyone in America was singing about their land being their land or about stuff blowing in their wind, was realizing what popular music could express. These seemingly unspeakable things that they went through could be depicted in song. Audiences loved them for it. However, as popular as this song was on French radio and in cabarets, something deeply insular was preventing it from spreading outside of the motherland.

Edith Piaf performing “La Goualante du Pauvre Jean” at L’Olympia (1953)

At that moment, Chanson had a definite end point. Something dealing so seriously with certain topics had to. Once, they made music to drink and dance, now they made music that drove you to drink. Fashion designers like Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, and others had already found worldly and artistic profitability through tasteful restraint. Musicians, however, were missing the bigger picture. At the end of the ’50s, designers like Yves Saint Laurent, artists like Yves Klein and Ben Vautier, or New Wave film makers like François Truffaut and Eric Rohmer had the right idea. Art can be made with that elusive quality, it can be both popular and accessible. But for that, you had to try a different approach.

The Chanson

What was it that Chanson musicians were losing then? What they were losing was nuance. In America, Jazz and R&B had shown this slippery ability to marry that concept of nuance with pop music. Somewhere else, an upstart style like Rock ‘n’ Roll had showed an even simpler third way. Chanson hadn’t gotten to any of those points. Edith Piaf rightfully complained about this:

I don’t like realist songs…For me they’re vulgar tunes with blokes wearing cloth caps and girls plying their trade on the streets. I hate that. I like flowers and simple love stories, health, joie de vivre and Paris.

- Edith Piaf

Enter, Boris Vian. That’s where we’ll pick up history next time…

Leave a Reply