The Fender Stratocaster has been my main guitar for years now, and despite the trademark five pickup positions that come stock on these guitars, I have always ended up using only one of them. While there are so many tones to explore on this instrument, I always end up falling back on position one, the neck pickup by itself. Numbers-wise this means that I’m using 20% of my instrument’s tonal capabilities for probably 99% of my playing. When I was finally able to lay my hands on a 1980s “Made in Japan” Squier Stratocaster, I felt like it was finally time to explore some ways to get the other two pickups involved.

The quest became exploring the options of the many different ways that pickups could be put together. I had played around with wiring pickups in series, or parallel, or even changing the way that they were in phase with each other, but instead of picking one combination and wiring it up, I really wanted to explore the possibilities available on my instrument before committing. What followed started as an “open audition” of as many sounds as I could try to pull from my pickups, but really became an experiment to explore what each of these combinations sounds like.

Methodology

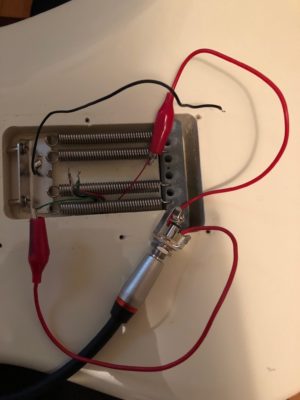

One thing I realized early is that to truly appreciate the unique characteristics of these pickup combinations, I would want to hear the sound of these pickups going directly into an amplifier. No tone pots, volume pots, switches, pedals, etc. would get in the way of hearing the pure sound of these pickups. To do so I had to go back to a favorite DIY tool of mine, which is the alligator clip quarter-inch jack. This remarkably powerful tool may be available in stores, but is more commonly (and cheaply) is acquired by assembling found parts. First, take an alligator clip cable, cut it in half and prepare the ends with pre-soldered leads. Then solder these two halves to the ground and hot lugs on a spare quarter inch jack, and voilà! You have an alligator clip quarter inch jack. You are now ready to start clipping leads willy-nilly to parts of your instrument, and seeing how they sound.

My alligator clip jack in all of its <$1 glory.

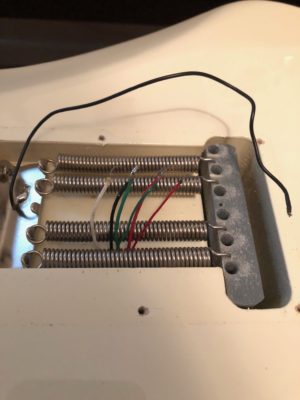

It was my turn to be baptized in the Fender river and awaken to the glory of heavenly tone when I was brought back to earth by a grim realization. All of the connections that I wanted to tap into were locked away under the pickguard, like they usually are on Stratocasters. I could easily take the instrument apart and start making connections, but aside from tapping something against the pickups to hear clicks and pops I wouldn’t be able to actually hear the character of the strings coming though them. I was resigned to the fate that my pickup leads, like peasants stuck in a castle under siege, would be locked away forever, until I remembered that there is always another way out. Like the proverbial well that leads to a back gate, my Stratocaster, like many, had a pre-drilled hole which allows for the ground wire to be connected to the floating bridge assembly on the back side of the instrument. It was a tight squeeze, but I was able to smuggle all six of my pickup wires through this hole and out of the back of the guitar.

- My neck pickup connected externally with my alligator clip jack

- Running leads through the back of the guitar

- Wiring notes

I had crossed many bridges, and was nearly ready to step into the promised land of tone when I realized that there was still one step I needed to take. I could play one sound, fumble around with some wires, and then play another, hoping that my sonic memory would still have an imprint of the previous sound I played. Or, instead, I could record everything I did and listen back to the recordings side by side to truly examine their differences. Honorable mention needs to be made at this point for my Boss BR-864 which was gifted to me by Santa Claus for Christmas 2003. While many have moved on to digital audio workstations in 2018 this multi-track recorder has proven to be my favorite, or most available, recording device all these years later. One major benefit of using a multi-track recorder here was that I could lay down each different pickup combination on a different track, and then use the volume faders to turn the tracks on and off and compare sounds. While the Boss BR-864 has sadly been retired from current inventory, there are many other multi-track recorders available if you find that this is a recording method you may be interested in.

My trusty Boss BR-864

In setting up to record, I realized that I would have to make this as scientific a process as possible. Of all the variables that I could introduce into this situation, I would only want one to change: the pickups I had plugged in. Everything else – the music I would play, the pick I would use, the gain settings on my direct input – would have to be identical, or else I may risk misidentifying a difference in sound caused by one of these external variables as something caused by the way the pickups were working together. To accomplish this, I fiddled around with a few parameters on the BR–864 which I commanded myself to not change throughout the process. Even when exporting these tracks through Audacity on my computer, I made a point to apply any edits to the tracks in the exact same way. Playing wise I came up with a little jangly chord riff, with a ’90s vibe, which proved to be taxing to my marriage over the hour or so I played it over and over again. It’s loosely based on two different songs, not necessarily ’90s though, so extra brownie points to anyone who correctly identifies them.

Reference Points

For starters I wanted to get a “control” recording of just the trusty old neck pickup by itself. This proved to be useful for identifying the individual characteristics of this pickup as well as having a comparison track when I had some other sounds to listen to.

As predicted, the neck pickup alone is its usual bass-filled self that I have come to know and love. Tonally, this will be the best representation of the low frequency spectrum out of all three pickups. Neck pickups, to me, seem to have the most presence or well-rounded sound for rhythm parts but are also full enough for playing leads without sounding shrill. This pickup also seems to live in the same space as the human voice as well.

While having three pickups affords three different pairs to investigate, I decided to keep this experiment down to just one pair and investigate the neck and the middle pickup. As such I needed a “control” recording for just the middle pickup as well.

The middle pickup on a Stratocaster has always seemed to represent some of the more goofy adjectives that are associated with guitar sounds. It still has a full feel, but with a dorky or awkward edge to it. If you’re looking for “twang” or “jangle,” you’re probably best off by starting with the middle pickup. To me, this pickup sound has always sounded closest to a Rocky and Bullwinkle vibe that you could get from a guitar. Despite this less-than-flattering description, it has also proven to be a valid sound for making good music over the years, and is a huge part of the signature Stratocaster sound.

Now that we have a base for what each individual pickup sounds like, it’s worth doing a side-by-side to compare their tonal characteristics. Looking back after having gone through the whole process, this following recording really helped in identifying the contributions of these two pickups to the sounds made when both are used at once. This recording alternates the neck pickup and the middle pickup each bar starting with the neck.

Hot and Ground Wires

Going forward you’ll start to see the words “hot” and “ground” used to describe the wires leading from the pickups. For all practical purposes, “hot” typically means the wire leading from the pickup to the output of the guitar, or the one carrying the signal that you want to hear. “Ground” is the other wire which completes the circuit. This will generally be connected to a structural, metal part of the instrument, and helps disperse any extra noise from your guitar signal.

Series v. Parallel

The first combination that I tried out was to have the neck and the middle pickup in series. You hear about series circuits sometimes when wiring light bulbs. Imagine having a power source like a battery with one end connected to a light bulb, and the connection out of that light bulb going to a second light bulb, all on one track. This is like your set of vintage Christmas lights that go out entirely when one bulb burns out.

We don’t have a power source like a battery in this case, but the concept is the same. For this setup I have the “hot” output wire from the neck pickup connected to the “tip” lug of my alligator clip jack. I have an additional alligator clip wire connecting the “ground” output of the neck pickup to the “hot” output of the middle pickup. Lastly I have the “ground” output of the middle pickup connected to ground. The following recording consists entirely of these two pickups in series.

You will sometimes hear of people referring to this combination as being louder than others, which has been my experience when putting other pickups together, but it didn’t necessarily happen in this case. What I noticed more in this case was that the overall sound seemed to be more heavy on the bass and midrange, while tapping off a good deal of the high signal. Having a more bottom-heavy tone like this might also contribute to what players experience as an increase in volume. That being said, you still get a taste of the tonal characteristics of each pickup, with the warmth of the neck pickup supporting the sound and a bit of the middle pickup’s “twang” coming through. This sound may be limiting when trying to play full choral accompaniment, but has a strong potential for driving rhythm parts into overdrive and distortion, or similarly distorted leads.

Next up is to take both of these pickups and wire them in parallel. Going back to our light bulb analogy, you would have one loop consisting of the battery and the first light bulb, and then an additional loop to integrate the second light bulb. This circuit consequently has the advantage of surviving one light bulb burning out while allowing for the other to glow, thus not ruining Christmas.

For this circuit on the guitar I simply clipped both “hot” outputs from each pickup to the alligator clip going to the tip lug on my jack, and then similarly had both “ground” clips connected to the alligator going to ground. The following recording is the complete audio excerpt with the pickups wired in parallel.

This sound is typically characterized by having a drop in volume compared to series wiring, but that didn’t necessarily come through with these pickups. What is noticeable is the clarity in sound when compared to the series circuit. The signature tonal characteristics of each pickup are coming through, but with much less of an emphasis on the low and midrange. The effect of listening to them side by side is almost like turning a tone knob all the way to ten, or spontaneously recovering from a wicked head cold. The following recording is a direct comparison of series and parallel wiring, with the first bar being series and then alternating to parallel.

Polarity

The next step in combining pickups involves playing with the polarity of each pickup. Since pickups use a magnet to induce sound, they have poles the same way a magnet does. When wired one way, the polarity will allow for hum cancellation in single coil pickups, and also allow the pickups to reinforce each other leading to a more full tone. If you flip one around while keeping the other the same, you end up with phase cancellation, which causes certain frequencies to cancel each other out.

The way to accomplish this with wiring is to reverse the way one pickup’s “hot” and “ground” wires are connected. When we had our pickups wired in series earlier, the ground output of one was connected to the hot of the other. To make this same circuit cause phase cancellation we keep the “hot” of the neck pickup connected to the tip of the output jack, with the “ground” of this pickup connected to the “ground” of the middle pickup. Lastly, the “hot” output on the middle pickup is connected to ground. The following recording alternates the series recording from earlier with this new series circuit with phase cancellation.

One notable difference is the drop in volume. Since phase cancellation removes a lot of output signal, it’s not hard to imagine why you wouldn’t get as much sonic output. Critics of this sound may cite this volume loss while also not approving of its hollow tone. That being said, there is still a niche use for this sound, with people appreciating the “quack” they get out of it compared to other pickup combinations.

I was about ready to pack up after this, but decided I would try to try to switch the polarity of the middle pickup for the parallel circuit as well. To accomplish this I connected the “hot” output of the neck pickup and the “ground” output of the middle pickup to the alligator clip leading to the hot lug on my jack. This left the “ground” from the neck pickup and the “hot” from the middle to be connected to ground.

As you can hear in the recording the results were…. interesting. One scientific term for the result could be “bad,” or at least something that would be hard to justify use of for a whole song. When you combine the lower output of a parallel circuit with phase cancellation, it doesn’t seem to leave much left. One comparison may be to the sound of a wah pedal when set all the way to the toe position, or a DJ rolling away all of the lows on a track. This may be a usable sound in places but might not get you hired again if you use it for an entire gig. Knowing this sound may be most useful when trying to troubleshoot issues in the wiring of your instrument. If you have two pickups that sound hollow, or are not giving you nearly enough volume, it could very well be that they are out of phase and that one needs to be reversed.

Observations

One takeaway I had from all this meddling is that instead of having some mega-Strat with dozens of tonal options under the hood, I would come away with a much simpler instrument. When it comes down to playing live there is simply not enough time to switch through that many sounds when there is music to be made. What this process did though, was help to clarify which of all the options really inspired me, which are the ones that I would probably end up wiring into the instrument. Silliest of all is that after exploring the furthest reaches of pickup possibilities, the best option might be the way the guitar was originally wired. It’s worth the trip to Oz, but you might just find out that in the end there’s no place like home.

As I delved into the reaches of what I could do with the three pickups on this Stratocaster, I began to think that this is a process worth doing on any instrument. No two pickups are the same, even when they are the same model by the same company, even the same person winding them, so there always may be some unique hidden gem waiting to be found. Maybe the neck and middle pickups on your first Strat sound great in series, but those two pickups your other Strat are best in parallel.

For now my ’80s “Made in Japan” Strat is still disassembled while I continue to explore what is available and digest what I have learned so far. While this journey is not yet complete, I feel like I am on the path towards having a custom instrument that I have fully explored and that truly speaks for me when I play it.