Welcome to Beat Connection, a series dedicated to promoting modern and vintage dance styles the only way we know how…by providing you a musical starting point to help you create that beat. In our previous post, we outlined a very important concept to think about when composing music: musical meter. Today, we take another step forward on our musical journey: pitch. Our goal: to give you the knowledge to understand how pitch works in music and what pitch can do for you.

Change nothing and continue with immaculate consistency.

- Brian Eno, from Oblique Strategies.

What Is Musical Pitch?

Pitch is like a construct, man. You know, sound waves. They go up. They go down. These things sound flat. These things sound sharp. Sounds can be pristine. Sounds can be…ugh, not so nice. But let me blow your mind today, boss. Many moons ago, the tyranny of western colonial powers decided that, like, 440 Hz is what all squares should set their right angles to. Musical frequency is easy to understand, it’s a measurement of how many times per second a sound wave travels in the air. However, you know how those International Organization for Standardization blokes up in Geneva, Switzerland are. They’re straight up totalitarian. You know them. They say that your microwave is really 900 watts, when your Hungry Man dinner begs to differ. Well, that same organization came to an agreement that certain frequencies at which musical waves travel should be identified by a standard note.

What you know as concert pitch, or the musical note A above middle C, wasn’t always set at 440 Hz. There was a time (around the 17th century) when grown folks – real intelligent people – were tuning their instruments so that same A note clocked in at 451 Hz, 409 Hz, and other frequencies. The creation of the tuning fork allowed groups to finally have some kind of standard to tune to. However, differences in quality, material, and frequency choice still made it hard to pick the “standard.” What composers were tasked with was to make higher pitched music. They wanted to go up in pitch, to a range most singers and performers weren’t comfortable in. Audiences wanted to hear some really merry as heck music – the brighter the better – dainty, sprightly stuff, so broken strings, and vocal chords be damned, the audience was going to have their insanely high-pitched “tra-la-la”-type of music. So, composers had their orchestras tune their instruments to a higher frequency range without any regard to a common pitch.

Some time later, performers who actually had to perform in these upper registers, started to complain about the humanly taxing intonation. Tuning to such a high frequency range put a lot of strain on human throats, musical instruments unaccustomed to those higher string tensions, and ear drums more accustomed to hearing lower pitched sound waves throughout the day. As music became a commodity, the Industrial Revolution allowed people to collect sheet music. In the past, it might have been fine for orchestras and churches to tune to their own frequency and tuning forks. Now consumers actually expected to hear the same piece sound exactly the same way, whether they’re playing it at home, or hearing it at the concert hall.

Concert Pitch

1939 was the fateful year when 440 Hz was decided on as the “happy” medium to have everyone tune their instruments to. A relic of that era when electronically produced clocks and machines couldn’t easily replicate a prime number, 440 Hz allowed everyone to transmit (and hear) a commonly decided-upon note: A4. Clearly, as you see now, frequency is objective. It’s only our human brain that likes to assign labels to something. That’s why pitch is subjective. You can tune to 440 Hz but should you have to? It’s a standard because it allowed composers to easily, mathematically figure out the notes around it. With those notes around it you’re able to produce an equal temperament distance.

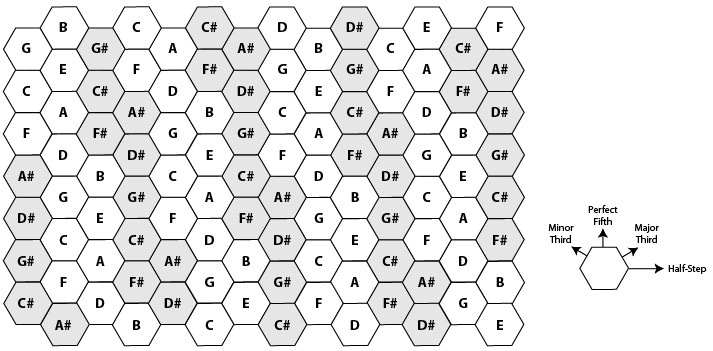

When you hear the words unison, major second, minor second, major third, minor third and so on, it means that those notes are in equal, mathematical intervals away. The distance between these notes are measured in semitones. Some mathematic theory made it so that if you multiply 440 by 12√2^n (n= the number of the note you want to get) you get seven notes on any given scale and the twelve notes on a keyboard instrument. Producing a unison note makes it sound consonant or harmonious. Producing a minor second means you went in-between two harmonious sounds to produce something dissonant or off-key.

Microtonal Music

The problem with concert pitch is that other cultures – Eastern, African, and Middle Eastern – have instruments that can produce frequencies found between “standard” Western equally tempered distances. Pianos and most fretted instruments have frets or keys to denote certain unseen limitations. You’re limited to 88 keys on a piano. You’re limited to a certain width, to produce a certain tone, on a guitar or violin.

Wind, brass, mallet instruments, and hand drums can produce overtones which are pitches that are slightly sharper than the harmonic or off-key pitches found in Western music. These in-between pitches, quarter tones that exist in between the notes of piano or frets on a guitar, aren’t a product of tuning to 440 Hz but of history and tradition. Other cultures have used other frequencies as their starting point for intonation. Likewise, that intonation allows them to create their own subdivisions to get scales and notes that divide an octave range far further than Western music does. Microtonal music might seem out of the norm, but it’s been the wider “standard” for longer than we know.

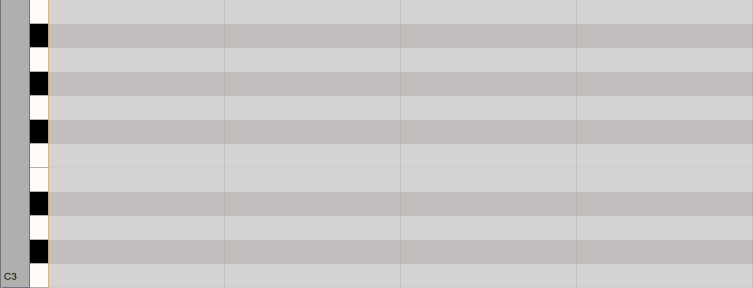

Making Pitch Your Stitch

When using software or a MIDI controller to make music there are obvious limitations to what you can do with pitch. A piano roll, or actual keys and pads, still give you a finite amount of notes to work with. No matter, what you have the flexibility to do with software is use tools within these interfaces to play around with other tunings. Something as simple as adjusting the virtual tuning knob on a plug-in can yield sounds that are musical, in a way that’s noticeably different from the expected. We’ll go over these tools in the future but MIDI effects like Scale, Chord, and Pitch allow you to play fast and loose with standard intonation. Sonic effects like Ableton’s Resonators and Corpus allow you to mimic some of the overtones present in non-Western music. If you see any control that says Tune or Pitch play around with that knob, on your keyboard instrument a Pitch Wheel or adjusting the spread of a portamento or glissando control can render those not-so-hidden notes. Play around, you’d be surprised with what musical ideas you can get out of these controls.

In real life, part of discovering different intonations and gaining access to different modalities is by tuning your instrument to a different pitch. For guitar, various resources exist on the web showing you alternate tunings that let you increase the range of your instrument and to tap into various sympathetic resonances that are simply unreasonable to reach using “standard” guitar tuning. Part of growing as a musician is realizing that outside of a typical rock band setup you will have to transpose or change the key of your composition (or instrument) to achieve some kind of musical harmony with brass, wind, and mallet instruments. What better way to explore a bit of the world of pitch than by taking its side roads?

Leave a Reply