Welcome to Beat Connection, a series dedicated to promoting modern and vintage dance styles the only way we know how…by providing you a musical starting point to help you create that beat. In our previous post, we outlined a very important concept to think about when composing music: tempo. Today, we take one more step forward to understand tempo’s musical partner: meter. Our goal: to help you understand musical meter and how it helps you arrange a song.

Take away the elements in order of apparent non-importance.

- Brian Eno, from Oblique Strategies.

Musical meter is that rare beast that eludes many of us. Most people can feel, hear, and understand the concept of why most music has a steady rhythm – one, two, three, four (repeat infinitum). However, many of us don’t have the foggiest idea why sheet music is marked down with this strange beast called time signature. 4/4, 3/4, 2/4 – common time, waltz time, and march time as they’re respectively known – are notations that outline something for a musician performing a piece, but the intersection of math and music can seem alien. These are common questions posed to most of us when understanding musical meter: What value does the top number have in relation to the bottom? What are they dividing? How important is knowing all of this?

Simple Time

My answer to these questions is to keep it simple. A time signature is simply telling you the number of beats in a measure and the type of notes found in that measure. The top value of time signature is how many beats you’re counting in each measure, “one, two, three, four.” The bottom will always be the duration of the notes within that count: “one…, two…, three…, four…” In this case, the second four denotes quarter notes. So, by interpreting the two numbers together, we get that we can fit four quarter notes in each measure. That’s 4/4 simple time in a nutshell.

Do you need a different amount of beats in the same duration of time? Count again, but this time remove the fourth beat: “one, two, three,” and leave the duration the same “one…, two…, three…” and you’ve got 3/4 time. Count more, “one, two, three, four, five,” and leave the duration the same “one…, two…, three…, four…, five…” and you’ve got 5/4 time. What you’re deciding is what the little metronome you see in your DAW will pulse to. It’s what will guide you as you press record.

Note: Each video below provides an example of what the time signature will sound or feel like.

In all music, before any song gets created, a composer must decide the pulse of the music and the tempo of the piece. A pulse is the heartbeat of the song. Let’s say you want to create a techno track. You begin by placing a kick drum on the first beat (the downbeat) of the count: “one, two, three, four”. This simple choice means you’ve also decided the pulse is 4 beats in total. By doing that, you’ve also decided the bottom value of that musical equation, 4/4.

Every measure (the musical term for a “repetitive musical section”) of that kick drum has four beats that a kick drum can land within a 4/4 count. Basic musical theory states that if you have 4 whole beats you can divide those further into two half notes, four quarter notes, eight eighth notes, sixteen sixteenth notes, and rests, so long as they add up to four beats per measure. So, in theory, you could have one half note and two quarter notes making up the whole measure.

The top number of the time signature is the amount by which you choose to divide the pulse. In common time, we’re choosing to divide the measure into four quarter notes – 4/4. Each division in common time is a one-two pulse, in a two-part rhythm.

Waltz Time

Let’s say you’re sick of normal techno or Pop music and you simply want to create something that’s a bit more laid back and groovy. You still don’t want to go far out with wacky time signatures, but you want to break up the monotony of the four-on-the-floor dance beat. To do this you’d have to drop a beat.

Count “one, two, three” in your head. Notice how the shorter repetition creates a certain shift in the rhythm, or structure, of your count. What you’re hearing is the dark matter of music, the existence of a rest that really doesn’t exist in notation. We say “one, two, three,” but we’re really hearing “one, two, three” and inserting a stress on the backbeat of the measure. It’s the only way we can divide this uneven musical equation.

Three quarter notes can be divided into six eighth notes, and those six eighth notes can be further subdivided into twelve sixteenth notes. Combine them at will — two quarter notes and two eighth notes, four eighth notes and six sixteenth notes, etc. — as long as they add up to taking the space of three quarter notes, you’ve got the makings of a measure in 3/4 time.

March Time

Let’s go even further and round out the final common time signatures. The remaining two, 2/4 and 1/4, simply cut the pulse of common time even further. With 2/4, what was once a count of “one, two, three, four” is now a count of “one, two”. Every count of this meter has a stress/accent on the first beat of the count and a weak stress on the second word of the count. ONE, two. ONE, two. If you’ve ever heard a march or a paso doble, you can instantly recall that quick burst of rhythm and meter.

Since we’re basically halving 4/4 meter, it also means we’re only working with two quarter notes to start off with. Of course, you can also divide those two initial quarter notes into eighth and sixteenth notes. As you can imagine, this 2/4 meter provides little room for sprawling melodic runs and works best for short bursts of repetition, in quick-and-to-the-point kind of music. Tex-Mex and Polka fans share something in common by using this uncommonly used time signature. Even some hits like Outkast’s “Hey Ya” use the not so common 2/4 time to great effect.

Compound Time

We’ve just learned common time signatures that are simple musical meters based on quarter notes that can be further subdivided into two parts. Compound time moves away from quarter notes and relies on eighth notes to gather notes in groupings of three, rather than two as in common time. 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8 time signatures are the most often used meters in compound time. This is music that sounds like it’s divisible into three groups of notes that cycle twice, three times, or four times, respectively. A normal count for 6/8 time would sound like this: “ONE, two, three, FOUR, five, six”.

Dotted notes, notes that increase the duration of any note by half its value, are commonly found in these compound time signatures. What this meter is trying to do is to always have the top number be divisible by three to squeeze in eighth notes evenly. Of course, you can even go more complex and try to rival the most out-there progressive rock masters. Double the bottom number, use sixteenth notes rather than eighth notes, and you can create even more complex time signatures like 15/16, 7/16, etc.

Polyrhythms

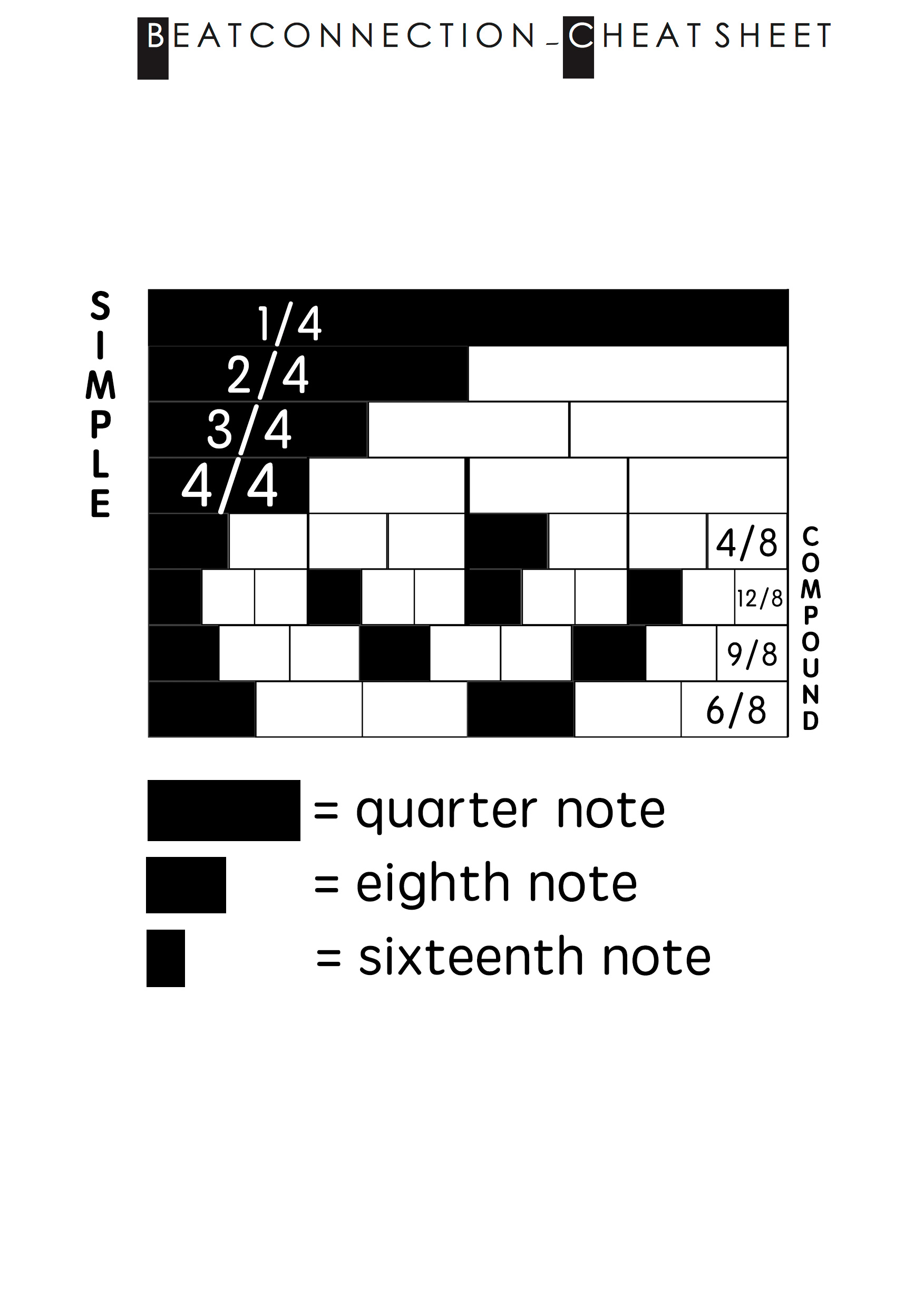

The key thing to remember is that most of the non-western world – Asian, African, Middle Eastern, and Eastern European areas especially – often deviate from common and compound time. A lot of music from these other musical hemispheres is polyrhythmic, where one instrument’s time signature might be playing a different meter than another instrument in the song. Most music that sounds complex on paper is quite understandable to your ear. The best composers tie different time signatures together, have 3/4 time blend into 6/8 for example, and bend time through their own will (and skill). The key is of course knowing how, why, and where to begin. Our Beat Connection cheatsheet below should give you a good starting point when trying to choose a musical meter.

Leave a Reply