“Class A” refers to a specific amplifier output design. Without diving too deep into electrical engineering, suffice it to say that Class A is the simplest, most basic circuit topology for an amplifier, and the easiest to design with less inherent distortion. Theoretically, you might say it’s a “perfect,” linear amplifier circuit: the output is an exact copy of the input, only louder. But this high fidelity comes at a cost of energy efficiency, because a Class A amplifier draws current and consumes power even when there’s no input signal present. That makes it great for preamps, but inefficient for power amps. That’s Class A in a nutshell!

Making the Grade?

When you see amplifiers described as Class A, AB, B, D, and so on, remember that it’s not a grade level or a rating! “Class A” isn’t an assurance of quality, and no class is inherently better than another — they’re simply different circuit topologies, each suited to different purposes. For example, Class D power amps are sought after for their efficiency, small size and light weight — whereas a Class A power amp for a big PA system would be a huge, heavy, expensive, electricity-hogging beast covered in heat sinks. Sure, big Class A power amps exist, and sound great, but they’re so profoundly inefficient that they’re rarely seen outside of the esoteric audiophile hi-fi community.

Single-Ended vs. Push-Pull

It’s a common misconception that all Class A amplifiers have a single-ended (also known as single-sided) output stage, as opposed to the (more efficient, more distortion-prone) push-pull output stage found in Class AB or Class B amps. A Class A single-sided design is the simplest, but some Class A amplifiers are in fact push-pull. And all Class A amplifiers are highly inefficient: at least half of the power they eat up is wasted as heat. A push-pull Class A amp could theoretically be 50% efficient, and a single-ended Class A amp tops out at about 25% efficiency, in terms of DC power in, vs. audio power out. In the real world, what this means is that your high-wattage amp can double as a space heater.

Class A = Always On

An amplifier is said to be Class A when it’s drawing current at all times, even when the amplifier is at idle, with no audio playing. Class A output devices never switch off; they’re always on, regardless of input signal. In a Class A amplifier, each amplifying element — whether it’s a tube or a transistor — is biased so it’s always conducting. As Wikipedia explains: “Because the device is never ‘off’ there is no ‘turn on’ time, no problems with charge storage, and generally better high-frequency performance and feedback loop stability (and usually fewer high-order harmonics).” Read: It sounds cleaner, with less distortion.

No Zero-Crossing Distortion

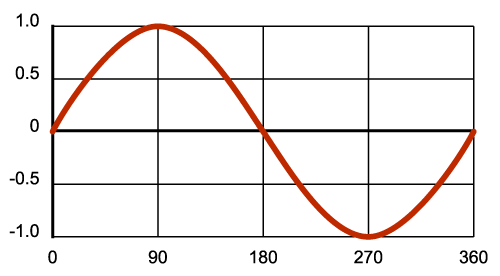

You may hear Class A amplifiers defined as “operating across all 360 degrees of the signal,” which is really just another way of saying “always on.” Think of your audio signal as a sine wave divided into 360 degrees. Zero degrees is where the signal crosses the center line and starts to travel upward, 90 degrees is where the signal is at its highest peak, 180 degrees is where the signal crosses the center line again and starts to dip, 270 degrees is the most negative point, and 360 degrees is where the signal meets the center line again.

The Class A amplifier operates across all 360 degrees of a signal.

Your Class A amplifier will output this entire waveform, but other classes of amplifier cover only a portion of the waveform. Class AB amplifiers, for example, operate over only 270 degrees, and Class B amplifiers operate over 180 degrees. You’d need two such Class B amplifier circuits (in a push-pull amplifier) to cover each half of the input, then reconstruct them after amplification to get the full signal.

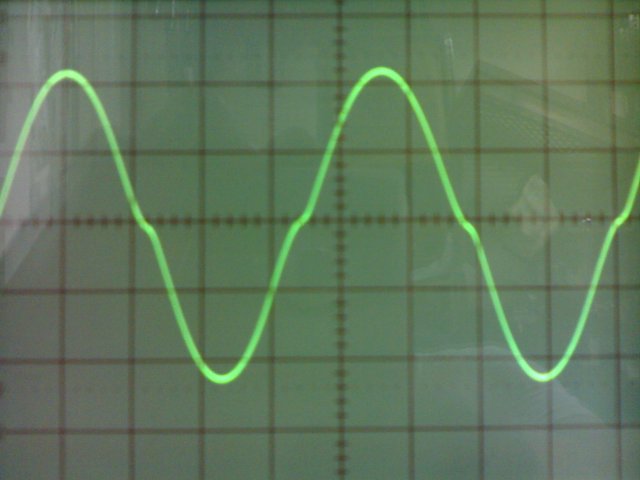

Imagine the sine wave above was fed through a Class B push-pull amplifier, so the top half is amplified by one side of the output stage, the bottom half is amplified by the other side, and the complete waveform is reconstructed on its way out. What could go wrong? Well, since each side is constantly turning off and on, the signal is susceptible to zero-crossing distortion, also known as crossover distortion. This specific kind of distortion is a “kink” in the sine wave, that occurs as the signal passes from the positive to the negative, or negative to positive. But a Class A push-pull amp is not susceptible to zero-crossing distortion, because each side of the push-pull amplifier is already “on.”

See that kink in the waveform as it crosses the center line? That’s zero-crossing distortion.

Why Class A Mic Preamps?

Although Class A output designs aren’t the most efficient for power amps, they’re a great fit for microphone preamplifiers. A microphone preamp is a device which boosts a very weak microphone-level signal up to a healthy line-level signal. Unlike a power amp, a preamp doesn’t need to produce a high-voltage signal that can move a heavy speaker around. So preamps don’t eat up a lot of power, and they can afford to take a hit in efficiency in exchange for low-distortion, linear amplification. That’s why high-end mic preamps are likely to be Class A, although there are also plenty of top-notch Class AB mic preamps out there.

“A” for Effort

In the end, “Class A” is an electrical engineering term that isn’t all that relevant when it comes to making music. Remember, Class A isn’t a rating, it’s simply a description of how a circuit works. Let your ears decide what sounds best!