No album has astounded listeners this year quite as much as Mariah’s Utakata no Hibi. From websites like Pitchfork, Resident Advisor, FACT Magazine, all the way down to the Quietus and the Vinyl Factory, not many albums released today could top such varied tastemakers’ “Best of 2015” lists, let alone with something originally released upwards of three decades ago — and with one listen, it isn’t hard to understand why.

Released in 1983, and reissued this year by Palto Flats, the album’s unique combination of Japanese Techno Kayo, No Wave Jazz, Eastern musics, and untraceable influences with vocals sung in either Japanese or Armenian (by Julie Fowell) set to some truly otherworldly, experimental pop music had very few peers to speak of then. It’s only now that we’re beginning to comprehend its creation — and have music that can fit alongside it.

Landing that rare combination of intelligence and accessibility, Utakata no Hibi holds a special place for many listeners who are still trying to understand and explain its creation.

mariah’s “shinzo no tobira” from Utakata no hibi (1983):

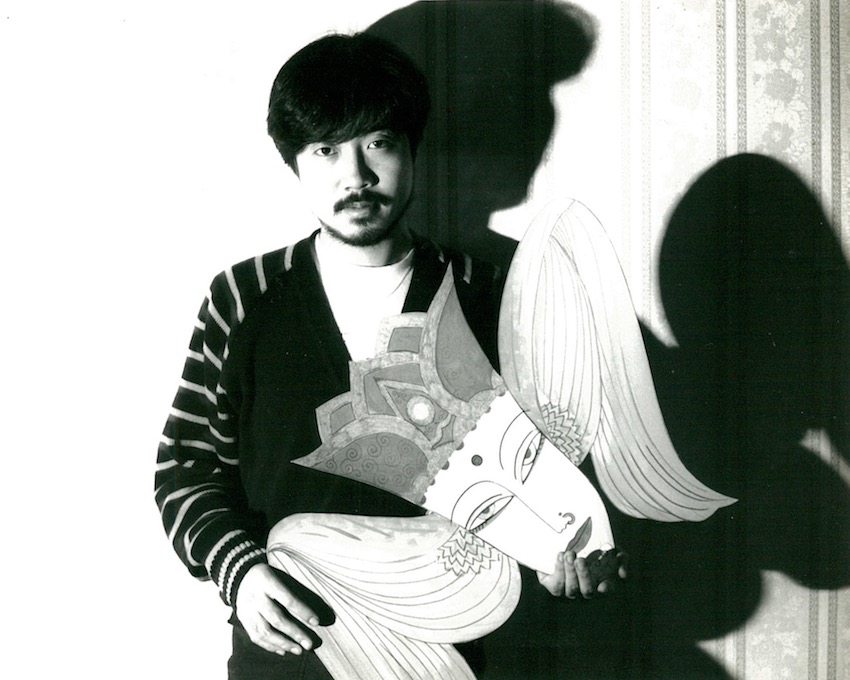

Before the exorbitant Discogs prices for this release, and the rampant speculation on who made it, there was a group led by the multi-instrumentalist Yasuaki Shimizu. Utakata no Hibi can now be seen, in hindsight, as the culmination of a body of groundbreaking work Yasuaki had been developing back in 1983. It’s something he hints at in our interview. From his beginning doing session work with notable Japanese artists like Taeko Ohnuki and Minako Yoshida, or sitting in with Haruomi Hosono helping craft experimental City-Pop classics like Mari Iijima’s Rose, and something of a decidedly different flavor like the jazz-fusion of Akira Inoue’s Prophetic Dream, it was his first love, jazz, that allowed Yasuaki to seek out new ways to rearrange the music he imagined.

When I listen to his brilliant work on Pierre Barouh’s Le Pollen, where Yasuaki seamlessly blends Japanese styles with French lyricism and Brazilian rhythms, I get part of the picture. When I turn to his own little-known masterpiece Kakashi, itself a breathtaking sonic slice of left-field pop, I get another splash on the canvas explaining a bit more of the world outside it — a world where even more Japanese music from this era has room to be discovered on our own shores. However, these albums released just a year prior to Utakata no Hibi can only take us so far in helping us understand the whole vision of Mariah’s masterpiece.

YASUAKI shimizu’s “semitori no Hi” from kakashi (1982):

What we’re missing is some insight from the man himself of what went on behind this release, and why Mariah existed and now ceases to exist. In the interview below, Yasuaki did us all a huge favor by taking some time to relate to us about this special time in his life. Jacob Gorchov, from Palto Flats, also graciously helps us understand a bit of what went behind reissuing Utakata no Hibi.

zZounds Interviews Yasuaki Shimizu (of Mariah)

on Utakata no Hibi:

zZounds: I’m watching a YouTube video of Mariah performing a track off Marginal Love. I’m struck by the difference in sound between that and what we would hear in Utakata no Hibi a year later. How do you explain this transformation?

Mariah performing “marginal love” from marginal Love (1981):

Yasuaki Shimizu: Wow, that takes me back. That’s Mariah performing on TV. I seem to remember doing a Doors cover after that. As you say, it’s hard to believe this is the same band who put out Utakata no Hibi. Mariah had released four albums before Utakata no Hibi, and although each was different, I guess they were standard rock albums, really. I grew a lot personally while we were working on the fifth album — I started having all sorts of new ideas, and at the same time, all the things I’d been cultivating up to then started coming together. Which was when I pitched the concept for Utakata no Hibi to the other members of the band.

zZ: Can you describe how Mariah was created, and why it ended?

Yasuaki: The first person I got to know was the drummer, Hideo Yamaki. We were in our mid-20s and utterly obsessed with jazz. We performed lots in groups assembled for the particular gig, with no permanent lineup. I was completely focused on how to communicate in improvised performances, and on honing the speed of my responses and the explosive power of my music.

Now I think back and marvel at the craziness of it all: performing in jazz club after jazz club, morning, noon and night, right through the night. One evening at a particular club, I happened upon a mesmerizing piano performance. That was Masanori Sasaji. When he’d finished, I asked him on the spot if he’d like to do some sessions with us. Sessions with Yamaki and Sasaji were pretty exciting. I then found myself however entering a new phase, mentally. Losing my all-consuming passion for jazz, from that point on, while I kept doing music, being driven by involvement in a wide range of fields outside of music took me to another plane.

Mariah from left to right: Takayuki Hijikata, Hideo Yamaki, Masanori Sasaji, Jimmy Murakawa, Yasuaki Shimizu, Morio Watanabe/ © Senji Urushibata (from Marginal Love inner sleeve, 1981)

There were lots of personal changes, bringing connections with new people. Sasaji and I however continued to explore music together while writing, arranging and producing tracks for pop singers. It was then that we first met what were to become the members of Mariah. Jimmy Murakawa just turned up one day and asked to speak to me. I’d never come across anyone as intriguing. Morio Watanabe and Takayuki Hijikata were playing in a rock band, and I met them when I performed with the band. Both Watanabe and Hijikata were great personalities, and I was enormously taken with them. I suggested to these five that we form a band. Incidentally, it was Murakawa who named the band “Mariah.”

Mariah’s first three years flew by. We had the typical band format, and used to see each other every day, like family. We rubbed along harmoniously, notwithstanding the odd big argument, but as time goes on, your individual interests begin to diverge. In our case this caused too much friction and the band broke up. Sasaji and guitarist Hijikata went on to form a new band, and have apparently worked as producers for a lot of Japanese pop artists, turning out numerous hits. I continued to work with Watanabe, Murakawa and Yamaki for a number of years.

zZ: I’m looking at your session work from that period, and it runs the gamut through all sorts of experimental pop music that people in America might know little of — everything from Taeko Onuki’s Sunflower, Mari Iijima’s Rose, to Pierre Barouh’s Le Pollen, to your own jazz albums. I know other musicians like Haruomi Hosono had similarly wandering tastes. How influenced were you by what else was going on, musically or culturally, in Japan at that time?

PIerre barouh’s “Parenthése” from Le Pollen (1982) COMPOSED by yasuaki shimizu:

Yasuaki: From early childhood, I was aware of having an almost freakish obsession with sound. I was born in the country, close to Mt. Fuji. Our house stood by itself, in the middle of rice paddies, which meant being surrounded by sounds of all sorts: a chorus of frogs in summer, insects in autumn. The chirping of crickets especially resonated with me. The sounds made by different types of cricket would randomly overlap, transmitting a kind of eternal music to the cosmos, it seemed to me. I was also into electronics at the time, and having noticed the resemblance between cricket song and Morse code, dreamed those bugs were communicating with aliens.

The chirping of crickets especially resonated with me. The sounds made by different types of cricket would randomly overlap, transmitting a kind of eternal music to the cosmos, it seemed to me.

My love of sound naturally extended to music. I listened to whatever music I could get my hands on, dabbled in all sorts of instruments as I struggled, agonizing, deep into the mysterious forest that is the connection between sounds and heart. What is it that stirs my soul? Whenever I think of sound, this is what I wonder.

zZ: How involved were you in the reissue of this album? I know it’s been difficult for American labels to license music made in Japan.

Yasuaki: Jacob contacted my office, and I immediately directed him to Columbia Japan, but it’s a miracle things have gone this smoothly. Japanese record companies don’t generally seem very interested in promoting the work of Japanese artists overseas.

zZ: The production work and sheer detail you hear on Utakata no Hibi sounds so effortless and contemporary, but I imagine that to actually pull this off took considerable effort. I mean, samplers, sequencers, and synthesizers from the ’80s aren’t known for their ease of use. Can you clue us in on how you pulled this off?

Living with sound as I did, I was always interested in sound art. From a young age I built my own oscillators, and also experimented with building things like amps and resonating wall speakers. I was also fascinated by the expression of sounds coming out of speakers, and got a huge kick out of trying, through trial and error, to record them.

Eighties recording equipment was good. I’m still using some of that gear. During the making of Utakata no Hibi we practically lived at the record company’s music studio, doing everything there, including the songwriting. And tried all sorts of things. Sequencers were around when we were making Utakata no Hibi, but I deliberately chose not to use them. We did, however, use the likes of multitrack recording and tape editing to achieve subtlety in the rhythmic expression.

Sequencers were around when we were making Utakata no Hibi, but I deliberately chose not to use them.

As for samplers, 4-bit models for guitar effects did exist, but this recording was mainly produced by tape editing. This meant doing things like cutting multi-tape on the diagonal, making loops about 20 meters long to cause howling, synchronizing two multi-tape recorders manually, giving the spring reverb a kick, gobbling up the microphones — well, maybe not that last one.

zZ: I know some of us might be looking forward to hearing more Mariah, but what’s next for you, personally?

I still have plenty I want to do. Obviously, carry on with the Saxophone-Bach-Space triangle concept. Exploring the possibilities of the pentatonic scale, too. Composing quirky orchestral music, electronic music, maybe something voice-dominated, film scores, which I just love and want to do more of. Just go off one day and play saxophone in a cave. Maybe have a go at something Neo-Mariah/Utakata no Hibi — who knows?

zZounds Interviews Jacob Gorchov from Palto Flats:

zZounds: What turned you on to Mariah’s Utakata no Hibi in the first place?

Jacob Gorchov: I don’t recall where i first heard Mariah, but I remember re-listening to it years later on a plane trip — probably 2011, 2012 — and remembering that I was really into it at some point. Shinzo blew me away again. After I was working on another project that didn’t come to fruition, I turned my attention to Mariah, though I didn’t anticipate what the project would look like ultimately.

zZ: How has the response been so far?

Gorchov: The response has been remarkable — I was not expecting the reaction to be as effusive. I love the record, surely, but was not aware how deep in the ether it was. It’s a testament to the amazing work of Yasuaki and the whole Mariah band, how important this record is, and I think as a kind of touchstone/flagship record for this type of music. But it also works as something that can be consumed by anyone, regardless of whether they were aware of the record, or introduced to it through the reissue.

That’s the one thing that’s really stood out to me — anecdotes of people walking into a record store, having no idea about the record, and hearing it/seeing it, and wanting to know more about it.

Utakata no Hibi – Album Cover

zZ: How important was it for you to present this release in a way that maybe the original wasn’t — to not simply do a straight re-release? It seems like everything, from the mastering process to the album design, serves as a refresher to this unique album.

Gorchov: For me, I think aesthetics are important — whether it means leaving some things the way they are, and subtly changing others. FYI, Palto Flats is not a reissue label only — the first record I released was new, and one of the next two is a full-length by a new band we recorded this year. But in terms of any reissue projects I work on, it’s a consideration, how I’d like to present them on a project basis. I think, and rightly so, that most people wanted the original format retained, even if they didn’t know what the original format was.

The artwork, of course, is stunning, but I added additional material — the label designs, another drawing, translations, printed inner sleeves; and of course having the original masters touched up — it’s a special record, and I’m extremely happy with how the repress was presented. I think the response bears that out — that people want quality records with a lot of attention to detail, that they can really appreciate, and spend a lot of time with.

zZ: Is there something else special coming up that we can look forward to from Palto Flats?

Gorchov: A new record by Woo, who are one of my favorite bands. They have released on Drag City and Emotional Rescue, as well as originally on Independent Project Records. The record, Awaawaa, comes out in mid-January. It’s a full length comprising unreleased recordings from 1975-82. It’s a remarkable record — krauty, dubby, synthy, and it fits in really well next to Mariah. Me, my friend Jan, and Clive/Mark Ives put together the record, and it really came out as a seamless whole. I think fans of Mariah will appreciate it — having video artists whose work I respect work on several videos for several of the tracks from the record.

FOLLOw Yasuaki Shimizu:

OFFICIAL SITE FACEBOOK TWITTER

Leave a Reply