Editor’s note: Victor Baker is no longer working on D’Angelico’s Master Builder guitars, but we’ve kept this interview up because it serves as a look into the intricate craftsmanship that goes into these guitars.

It’s a New Yorker made by the hands of a New Yorker in New York.

To clarify, that’s a D’Angelico New Yorker archtop guitar, re-created as an original by prominent New York luthier Victor Baker, in D’Angelico’s Astoria workshop. It couldn’t get much more New York than that unless Billy Joel wrote a song about it and Woody Allen shot the music video.

D’Angelico recently launched its Master Builder series, hand-crafting jazz archtops the way founder John D’Angelico was doing in New York starting in the 1930s. Considered among the finest American guitars ever made and perhaps the finest jazz archtop guitars, vintage D’Angelicos fetch top dollar on the vintage market, but up until recently guitarists who couldn’t afford collectors’ prices had few options in the way of recreations. D’Angelico’s Master Builder line is a way to preserve John D’Angelico’s legacy and introduce his style of craftsmanship for a new generation.

The man they tapped for this prestigious role is New York-based luthier Victor Baker. In many ways, he’s the perfect candidate: he already had plenty of reverence for D’Angelico, having grown up reading books like “Acquired of the Angels,” which chronicles the careers of John D’Angelico and partner James D’Aquisto. A guitarist in the New York club scene, Baker also turned many players on to archtops he made for his own company. Now, with a small team of two other luthiers, Baker is bringing John D’Angelico’s originals back to life in stunning detail, as well as building custom D’Angelico models.

We recently got to speak with Baker on his process, the challenges and the rewards of working on these guitars.

A completed D’Angelico Master Builder Excel.

zZ: Growing up and performing as a jazz guitarist in New York and building archtops, I imagine that D’Angelico had a place in your mind or heart in some way.

VB: Oh yeah, I mean if you’re a player, it’s like thinking of Wes Montgomery or something. It’s where a lot of the language began. John D’Angelico started way back in the ’30s and ’40s pioneering the instrument along with Gibson and along with just a handful of other names that were making jazz guitars. But the level of refinement and involvement with the New York City jazz scene, there’s just no one else. Then he passed the torch to [Jimmy] D’Aquisto when he passed away and Jimmy continued the heritage of it. But that’s where the root of it all started, as far as the ’50s and ’60s jazz guitar evolution.

Jazz guitars in general have a lot of ornamentation as far as the binding and inlay stuff but D’Angelicos are the pinnacle of that, with the whole Art-Deco thing, the New York-vibe and all the engravings, that sort of stuff. You get this beautifully ornate instrument at the end and it’s just seeped in jazz guitar history.

zZ: As a performer, were you a D’Angelico player?

VB: Oh no, because I used my own instruments! (laughs) It would look bad for me gigging around town with a different brand than my own.

Victor Baker performs on one of his own guitars.

zZ: Is it just you working on the Master Builder guitars?

VB: There are three of us in my shop. I had a two-man crew plus myself when I was doing my own instruments and we just switched right in to doing D’Angelico stuff. The two guys I work with I took in from scratch pretty much, taught them the trade as I know it and they have a really great skill set, they do a lot of different operations in the shop. I’m obviously the one that’s doing all the heavy designing work and making sure everything is running super smooth, but there are definitely things I entrust to those guys too. It’s a small team. I think D’Angelico is going to approach this as a very small run, limited-edition kind of custom shop, but there are more than two hands involved. I’m definitely setting things up and using my expertise to make it work, but yeah — it’s nice to have some skilled hands and I definitely have some help on it.

Clamping down on a Master Builder New Yorker’s top in Baker’s workshop.

zZ: When recreating those original D’Angelico models, what documents or resources do you have to work with?

VB: Well, it goes back way beyond from when I jumped onboard. Just as a jazz guitar fan that was getting in the building when I first started — this was like late ’90s — I bought every book there was on jazz guitar just trying to glean any angles that I could as to what was happening on the inside, so I knew about John’s work. So basically I memorized the “Acquired of the Angels” book and a couple of other publications and I kind of geeked out on it.

Some things they give me models for, like the DC, the SS models, the semi-hollow guitars, but the older instruments, the classic ones, they had done some work with a company and had them laser scanned and MRI scanned. So they gave me the files on those vintage instruments and they were obviously a huge help, but I mean these were very old guitars so they might have been twisted or misshapen. So, I taught myself how to do CAD for blueprints. It was really cool seeing the old instrument, but it wasn’t really quite ready for production because I had to straighten it out and put it back to where I thought it would be when it was brand new, minus 50 years of aging and use. But I definitely think I got it. The first New Yorker came out a few months ago out of the shop, and it plays great, sounds great and it’s just a big, big Cadillac of an archtop, it couldn’t be more fun to play. There’s always an evolution and a refinement and the computer stuff gets you really far, but after that, you know, you’ve got to flex the top and fine tune things from there.

But each guitar is different and that’s what happened with John as well — he had a lot of helping hands that helped shape his instruments. It seems like no one in this process at D’Angelico is an island, I mean John obviously had Jimmy D’Aquisto in his shop, but those other guys that did a lot of the roughing work and he commissioned out a lot of the brass work like the tailpieces and all that stuff. So it’s definitely a New York collaborative process with these guitars.

Preparing the New Yorker’s neck.

We’re going to be doing custom shop, so I’m sure I’m going to be meeting artists and tailoring an instrument to what they want, which is essentially what John did. So you might see a vintage instrument that has certain measurements, but it’s not quite the whole picture because he might have built it that way for a certain person’s preferences or a certain person’s anatomy or for a certain application. I know that from doing all the custom work in my own shop. I’m approaching this with the same mentality as I did with my own instruments while trying to think though the window of how John might have done it. Talking to the player, asking them what they want to do with the instrument, where it’s going to be played, how it’s going to be played, that kind of thing. And from there you make adjustments, whether it’s physical, like neck width, scale length that type of stuff, but then also tuning the top of the instrument. If someone’s going to be playing in a loud situation all the time, you might suggest a certain style of carve for the soundboard and the backplate. It’s endless; there’s so much stuff going on, but having the original framework digitally produced from the beginning, it saves so much time.

I went down to inspect an instrument owned by someone here in the city and I had to bring my contour gauges and calipers and take measurements right form the vintage instrument. That’s definitely more time-consuming because I have to reverse-engineer the instrument from scratch, but that’s going well, it’s just more steps. It’s not more difficult, it just takes a little longer because you have to start from a couple steps further back. But it’s fun; I’ll spend hours on it and not even notice the clock.

Clamping the sides of the New Yorker.

zZ: How many of these original recreations have you made up to this point?

VB: The original guitar I made — pretty much my proposal guitar I made to get the gig — was a 1942 Excel. That turned out really well and then I did a New Yorker and then, they’re not quite finished yet but I’m doing a small run of Excels and Style Bs and those are being painted and then right now we’re on the SS models, DC models. I’m trying to get their whole line set up for them so we can unveil it next year at the NAMM show, have a big lineup of the guitars. Once I’m done with this design and setup phase, I’m sure the guys will come at me with what they need as far as work orders. But right now this year is basically just getting the shop turned over from my instruments to their setups. I have to make new jigs, new molds, new workflow patterns. Basically the second half of this year is just getting tooled up and raring to go, getting all the first guitars out. And it’s going really well, everything’s coming together, no bumps in the road. Jazz guitars are very time-intensive. They take a long time to get made just because of the steps involved; it’s not like a Tele or something.

zZ: About how long on average does it take to make one of these guitars?

VB: That’s hard to say because I’m also developing at the same time. Shooting form the hip, between 75 and 125 hours per instrument. And that’s the same case with my own instruments, when I made my own guitars. On a good year when I was working purely by myself doing all steps, I’d probably make about 30 guitars a year. Obviously D’Angelico is gonna be bigger than that just because I have two guys helping me out and there will be set models and that type of thing, but I’m sure they’re going to want to do a limited-edition custom run of something. We were kind of going back and forth with ideas and thought if we meet somebody who has an old New Yorker or a non-original, we might ask to duplicate it and do a limited run. So that’s kind of the idea of the Master Builder line is working with artists or doing limited runs like that. Obviously having some consistent models that we have available, but with the open possibility that there are all kinds of things on the table.

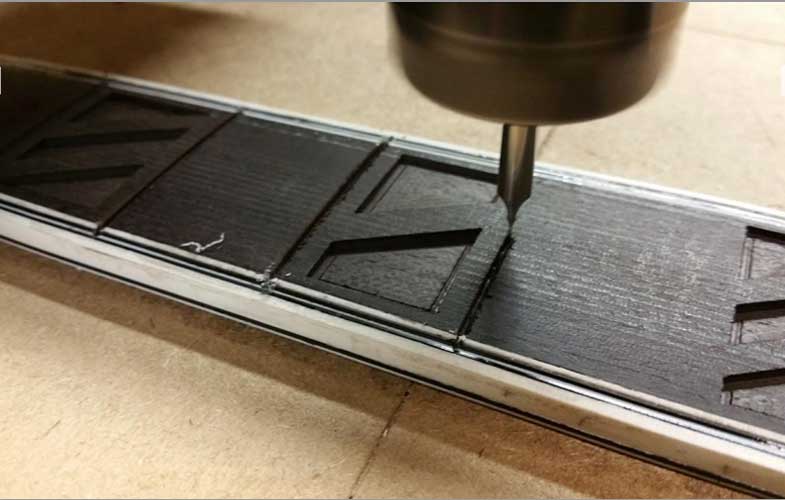

Carving out spots in the New Yorker’s fretboard for inlays.

zZ: Any parts of the process that you found to be particularly challenging?

VB: I mean, a lot of the problems I solved on my own instruments years ago, but just the heavy binding work. I mean, when you think of D’Angelico you think of big heavy binding and pearl. And that’s the guitars. The pearl work is definitely challenging, but the binding, just to get all those clean lines around the perimeter of the guitar and headstock — I have a lot of tricks up my sleeve of how to do it through things I’ve taught myself over the years, but also through things that are available to me as a modern builder, like I can cut out things in a way that would have been impossible in [John] D’Angelico’s day, but when you look at the two [guitars] they’re indistinguishable. I’m sure any craftsman from any era would welcome a new tool in their toolbox. So I definitely build in a modern way, just because it’s 2015 and not 1955.

Inlay work on the New Yorker’s headstock.

zZ: What to you sets a D’Angelico apart as a New York guitar?

VB: Well it’s the Art Deco thing. I mean, you look at the Chrysler Building and you see those lines; you look at the Empire State Building. D’Angelico was building his guitars when those things were happening. You see those lines in his instruments and just that mentality with the New Yorker logos, the tailpieces, and everything has that New York City skyline vibe to it. And so to have a New Yorker that’s made in New York again, it’s a certain thing. I think there’s gonna be appeal out there, a lot of appeal. Because it is New York. I mean D’Angelico out of necessity has to have an import line. And the thing of it is, I’m just so impressed with those guitars. The price point that they’re offered at, I mean they are so much bang for the buck, they have a lot of good things going for them. And I personally play one, I have one of the SS models. And you know what? I like it; I play it. I still play professionally and I’ll take it out to a gig and I like it. I think I’m gonna have a stronger connection when I build one and everything’s gonna be top-shelf, but you know for what they are, those import guitars that bear the D’Angelico name, they’re not cheap.

zZ: Who would you say is the target customer for these Custom Shop D’Angelico models?

VB: Let’s face it, the jazz guitar market is very small, compared to other genres of music. And I know they’re reaching out through all kinds of different players in different genres, so I could see these guitars going in a lot of different hands and being used for a lot of different things. But if you’re talking about the reproductions of the big old archtops from way back yesteryear, I would say a lot of guys that play jazz, a lot of guys that are fans of jazz, that are aware of that history, that heritage, that appreciate that level of refinement in an instrument, speaking of those lines and that Art Deco vibe. It’s a strong brand and it’s a strong vibe in an instrument. And what my challenge is going to be is to not only cater to those people, but what I want to do with the company is to broaden that appeal. Put an oval archtop in the hands of a country player and see what happens. It makes sense as an alternate instrument for an artist — they have their steel-string flattop, then they pick up an archtop for a different thing. And then also with the semi-hollow guitars, especially with the SS and the DC, those can go in any direction. I could even see heavier rock players playing an SS, with the right rigging and setup. And I think I’m going to be doing some solidbodies too for them that have the D’Angelico vibe. Obviously [John] D’Angelico never made solidbodies, but why not? I personally think John would have made anything that someone asked him if they had a need. So I don’t have any qualms making anything that somebody wants, obviously within the parameters of what D’Angelico is about.

Setting the bracing on the New Yorker.

zZ: Are you wiring and assembling the pickups yourself for these models?

VB: I know the guys are experimenting; we’re testing the water. There are a couple of different pickups they have in mind. It’s going to be an evolution: we’re trying to figure out what we want to match with which guitar. I’m so early in the process that I’m just assembling instruments; I’m in the construction phase. Only a few of the guitars have gotten out with complete setups. I think the first guitar had a [Lindy] Fralin on it, then the New Yorker had a Benedetto S6 floater on it. But that’s still very much in the air, we’re still working on what we want to put on them. And also I’m sure it will depend on the artist. Whatever their preference is will be what goes in the guitar.

Kent Armstrong’s pickups have always been a go-to for me in my own line and I know [D’Angelico] uses Kent Armstrongs in a lot of their other instruments like the import series and that sort of thing. If someone was asking me for a jazz guitar pickup that would be my first recommendation. I’ve been working with Kent for years and years. He makes them in his house still and they’re very limited run or made-to-order.

zZ: Have there been any challenges in re-creating the originals as far as scarcity of tonewoods?

VB: No, I’ve been doing archtops for a long time, so I have my sources that I’ve been using in place already, but there aren’t many places where you can buy the wood. What I buy is from the same regions as violin makers and cello makers, double bass makers they buy their stuff. IT’s in Italy, the Alps, mountainous regions in Europe. There’s some German spruce still available but it’s all pretty much the same tree. Different regions have different altitudes, so you get a different grain count and maybe a certain flavor of sound. But tonewoods will definitely be getting more scarce as time goes on, but for now I have what I need. We’re getting all kinds of different materials — we’ll use stuff from the Pacific Northwest, I’m getting some exhibition-grade quilted maple, we just bought to do for a New Yorker. So that’s domestic woods, I’ve had great success with using Sitka spruce on my own guitars, so I’m sure that will get rotated in. It depends what the player wants, what kind of sound — different woods carry a different voice. You can’t get quilted maple from Europe, the trees don’t grow that way. So if we wanted to do an instrument with quilted maple it would have to come from Canada or the Pacific Northwest region. It’s not a huge database of places you can go by this stuff, but I can get it. It’s always a challenge and it will be more and more of a challenge as the years pass, but I know where to get the good stuff, if you know what I mean.

zZ: What to you defines the sound of a jazz archtop?

VB: Well I’m not sure I can quantify it. As a description, the top’s carved and shaped much in the way a violin is, which is one of the things John helped refine in his instruments. He wasn’t the only inventor of the archtop-style guitar, but he definitely was a pioneer in adopting ways of carving instruments from the violin family but adapting that to guitar. The definitive quality of an archtop guitar? There are so many flavors to them and different ways that they’re used. But personally I would think it’s carved in a violin-based tradition, that’s what sets it apart from solid bodied guitars.

The sound comes off of an archtop to me, as opposed to out of a flattop. Like if you picture a normal Martin-style flattop guitar, to me the sound comes out of the soundhole, out of the air inside. But for me the archtop is a different inflection of sound. To me the sound comes off the guitar. It could be the same decibel level if a guitar is carved in such a way to be that acoustically active, it can be the same level of volume, but if comes off of it, to my ears. Now electrically, when you have air inside the instrument, it’s kind of hard to describe without stating the obvious — if there’s air inside the instrument, there’s air inside the tone. Like a solidbody guitar won’t have the same air quality to the tone. Beyond that it’s like describing what chocolate tastes like without handing you a candy bar and letting you take a bite; then it’s self-explanatory. But if you can picture the bridge position pickup on a Stratocaster and then picture an archtop with the neck position pickup, it’s just a world of difference — there’s so much more warm, open tone to the sound.

zZ: Not to generalize, but it seems like a large quantity of guitarists in any genre seem to have a reverence for guitars made in the mid-20th century — what do you think is behind that?

WB: It’s just human nature I think, the fondness of yesteryear — the good old days. Those guitars warrant that reverence, there’s no doubt, but there’s always a reverence of yesteryear. Seeing something from a bygone era triggers that sentiment in people. And that’s the whole idea behind doing the reproduction work is to give that vibe to people without having to spend the money that the vintage instruments command. What I’m trying to do in the Master Builder shop is make a little of that available. Of course, I’m not John D’Angelico making the guitars but I’m working from his lines. And with the digital reproduction work that I started my recipe from, it is the recipe. I had to do a lot to make it reality, but at least I’m starting from his lines and where the guitar actually was. And that’s what’s exciting about it because then you see this guitar, it’s made in New York, it started with John’s designs, it’s as close as we can get in the modern day. This is a D’Angelico from New York. It’s my task as a builder to have a certain level of refinement in my abilities to meet that standard not only phsyically and technically but with reverence and nostalgia and sentiment.

The newer guitars like the SS and even the solidbodies, those aren’t vintage reproductions, those are new, those are now. So I’m incorporating a lot of the things that I did on that kind of guitar on my own line to make those instruments. But it still has that connection, it still has that Art Deco vibe, that sensibility of D’Angelico. Obviously I have to do a lot of interpretive things just to make everything work, I have to make the call. And it’s so far, so good, everything’s working out really nice. I’m satisfied with the guitars and the few that have gotten out there already have been positively received and it’s just a matter of getting more and more set up and capable of producing something that a player has in mind and taking requests and engaging on what John might have done. It’s really exciting, it’s a lot of fun. It’s a dream gig for a luthier, I’ll definitely tell you that.

I’m just anxious to see what unfolds. Obviously I’m the one steering the ship but I’m enjoying the voyage. I can’t wait to see what guitars come out of the shop, what the retail guys at D’Angelico ask me to do, what requests we get, how the guitars are received, which guitars are favorable, and which are more for a niche market.

All images credited to: http://www.victorbakerguitars.com/blog/