Destination: Osaka, Osaka Prefecture, Japan. Roland Corporation Headquarters, 1977

We might not realize it, but the Roland company we know now is entirely different than the one it was shaping up to be in its early days. When Ikutaro Kakehashi, founder of Roland, started his first venture into musical instruments, it was indebted to his love for time. In 1932, at the age of two, Ikutaro lost both of his parents to tuberculosis. As a young boy he had to make a living fixing Kairyu submarines in Hitachi-run Japanese military shipyards. Once the war was over he was refused entry to Osaka’s university on account of his poor health. Searching for a solution to this predicament and a steady job (having been forced to forgo his education) he traveled to Kyushu, the southernmost province of Japan. There, he discovered something brilliant: Post-War Japan had virtually no timepiece industry. Mirroring the beginnings of a young Torakusu Yamaha, he took a job as a watch repairer.

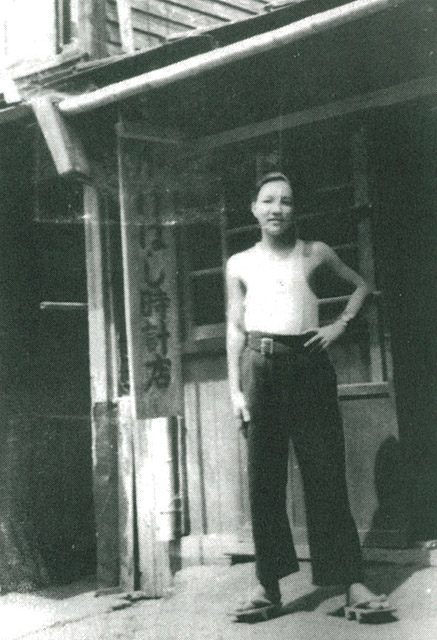

Ikutaro Kakehashi in front of Kakehashi Watch Shop.

Kakehashi was 16 or 17 years old when he set about to learn in mere months what took years for many to learn through apprenticeships. In mere months, he set up the Kakehashi Watch Shop as a base to start his own ventures. With money raised from repairing watches, Ikutaro turned his eye towards music and the radio industry. Just years ago, even owning or listening to foreign radio transmissions was deemed illegal. Now, here, in Kyushu, Kakehashi was making or repairing devices that were an expression of freedom in Post-World War II Japan. When he finally earned enough money from his shop, Kakehashi turned back to Osaka and decided to use these funds to pay his way back into Osaka University. Unfortunately, once again tragedy struck.

Spotlight:

This post is part of a larger discussion on the way Electronic Dance Music has evolved alongside cultural and technological history. As part of this series, we’re highlighting elsewhere one of its main influencers: The Berlin School of Electronic Music. There you’ll be able to see the role a certain drum machine, revealed here, would play in shaping EDM.

Click here to Visit the Berlin School…Time Stands Still

At the age of 20, rather than spend his money on education, Kakehashi had to pay for tuberculosis treatments. For three long years, he was consigned to a hospital ward, only repairing electronics for the hospital staff or other patients in order to support himself. Right before he received Streptomycin, the experimental drug that saved him from his terminal illness, so driven was Kakehashi to view Japan’s first TV signals that he used most of those savings to purchase a vacuum tube to create a television to receive them. In 1954, when Kakehashi finally had the strength to leave, he opened an electric repair shop post haste. In the span of six years, as radio and TV technology grew, he solidified the new business’ name as the Ace Electrical Company and earned enough money to try something different. As the Ace Electrical Company became Ace Electronic Industries, so did a shift toward a new kind of product.

For years, Kakehashi tried to branch out into the music market, following an intriguing product that piqued his interest: the theremin. Influenced by Dr. Bob Moog, Kakehashi tried to build his own theremin. His first creation didn’t sound quite right, but undeterred, Kakehashi moved on to creating a keyboard instrument. Hearing and seeing the Ondes Martenot in action, he used bits from reed organs, telephones and other transistor sound generators to create his own version. This too was another misstep and the instrument never went to production. By 1959, rather than redesign the wheel, he designed and released an organ: the Technics SX601. It was the success of this organ that allowed Ace Electronic Industries to add guitar amps and pedals to its product line. However, by 1963, something new had stirred Kakehashi’s interest: the Wurlitzer Sideman.

Released in 1959, the Sideman was revolutionary in few ways people envisioned. Using tape loops, this self-contained device allowed users to play 12 predetermined drum patterns at varying tempos. A whirling disc would cycle through different electronically generated drum sounds. Using this device, any musician could have drum accompaniment without an actual, physical drummer. However, what interested Kakehashi wasn’t this per se, but the idea of an electronic percussion instrument. In 1964, when he introduced the Rhythm Ace R-1 at NAMM he introduced his version of a drum machine.

This drum machine had no preset rhythms or patterns, it was a true drum machine in this aspect: when you pressed a button you heard a corresponding drum sound. It was a drum pad…before the idea existed! Such a revelation was met with deafening rejection for the next three years. The Rhythm Ace FR-1, released in 1967, added a concession for the market (preset patterns) that allowed it to become the standard add-on for nearly anyone who bought a Hammond organ those days. Compared to the enormous Wurlitzer, Kakehashi’s Rhythm Ace, made more compact in size by its use of transistor parts, negated any more exploration of the electronic drumming part. If, the drum machine playback was handling the duties so well, what use was their to explore purely electronic drum playing? The FR-1’s success would set in motion what would turn Ace Electronics into something else altogether.

Time Keeps Ticking

In 1971 Kakehashi cut ties from his own company, and by April 1972, had started Roland to regain the control and inspiration to create musical products he had started to lose. Unable to compete with brands like Yamaha and Kawai in making established musical instruments, Kakehashi decided once again to refocus on one that was never given its due: the rhythm machine. In 1972, with only $100,000 to his name and a staff numbering in the single digits, he swiftly and quickly introduced three rhythm machines; the TR-77, TR-55, and TR-33. It was those drum machines that kept company afloat and let it gain enough traction to create some wonderful products we treasure today.

Disparate, varied products like the Roland EP-10 electric piano, the RE-201 Space Echo, the Roland Jazz Chorus guitar amp, the Roland GS500/GR500 guitar and System-100 modular synthesizers were some of these. However, as great as those were, they were great variations on a theme. So, focused on these other industries somehow Roland lost sight of one track that got them there to begin with. It’s the one that would make Roland truly unique, courtesy of a few unsung heroes, ones that would have a far greater impact on our own musical future.

Cracking the TR-808 Genetic Code

- Roland TR-66 Rhythm Arranger

- Roland CR-78 CompuRhythm

- Boss DR-55 Dr. Rhythm

Taking bits of history from the Roland TR-66 Rhythm Arranger (released in 1973), the Roland CR-78 CompuRhythm (released in 1978) and the Boss DR-55 Dr. Rhythm (released in 1980), now we have something that can launch a revolution, one that harkens back to Kakehashi’s original Rhythm Ace R1 creation. It’s what would change the drum machine from a mere accompaniment device into something else.

TR-66: From the TR-66 we gain the ability to go beyond simple preset pattern variations. The TR-66 introduced the idea of combination. Rhythm Arranger users could press two or more patterns, and add three different pattern variations, to get a combination of hundreds of new drum rhythms. Completely analog in sound, it started to reimagine the idea of this machine having simply preset destinations and gave it room to improvise.

CR-78: The CR-78, the first rhythm machine to use a microchip, added another strain of thought: the idea of creating your own patterns. You could enter and store your own two-bar beats step-by-step on either a a WS-1 button switch or onboard buttons, to create and store up to four rhythm patterns in total.

DR-55: From the Dr. Rhythm DR-55, we gain access to a zen koan: “less is more.” Extremely compact/portable and incredibly basic, taking it at face value does not justify its worth. Digging deep, you realize why it solidified this perfect bridge towards our modern drum machines: the DR-55 thought of itself as its own instrument. Dispensing with any preset patterns altogether, providing the most basic of programming controls (tempo control, pattern length, and basic drum tone control) while focusing on just four sounds (hi-hat, snare, kick drum, and rim shot) made it seem like Roland aimed to provide a simple practice tool for musicians. However, its focus on simplicity gave it a unique edge hardly any other sequencer had. Simply set a switch to WRITE, pick a sound, hit START where you want a drum sound to appear in 16 (or 12 of the steps) and hit STOP when you want it it to skip a place. Switch back to PLAY and voila — you’d hear your first drum beat.

Timing Resets Time

All of these philosophies came together for the masses later on in 1980 when Japanese electronic drum band Yellow Magic Orchestra debuted the Roland TR-808 on-stage, and in the studio, with “1000 Knives.” It’s hard to quantify how much freedom the TR-808 presented. Freed from preset patterns, and with much more control over the contour and shape of the drum sounds themselves, it placed the focus or responsibility of all drum rhythms on the musician. Trusting that a musician could create their own electronic rhythms far different than the standard Cha-Cha, Beguine, Foxtrot, etc., it signaled a sea change in musical thinking.

Once before you didn’t have to be a pianist or organist to be a keyboardist, now you didn’t have to be a drummer to drum. When Ikutaro Kakehashi created his first drum machine way back when, he had germinated this idea. If it took 16 years to fully realize what he was thinking about then, Roland understood now. It’s this instrument, now truly joining the stable of a new class of musical ones, like the sequencer, sampler, and computer, that would pick up the mantle for electronic dance music and it’s where you can start envisioning its imprint on a changing culture.

Check out a video performance of the Roland TR-808 assisting Yellow Magic Orchestra on hand claps and claves:

Leave a Reply