The Musical Almanac is an ongoing series highlighting musical styles or genres from around the world. Today, we focus on a unique style from Ethiopia.

What’s Ethiopian Jazz? Imagine the “free” sound of John Coltrane meeting the impressionistic music of Debussy. Then, imagine all of this accompanied by African and American soul polyrhythms…that’s a start, but it can also be much more than this. You’ll see what we mean…

If you ask any Ethiopian to name the person who birthed their music, most would utter the name Yared. It’s through Yared, and other musicians a millennia and more later, we’ll start to hear how a shared history birthed this new sound.

Saint Yared

Born in the 6th century to an Aksumite family with a distinguished lineage of Christian church scholars, Yared’s life was prescribed to follow in his family’s devotional work. The problem was that as faithful as Yared was to his education and religion, he was equally as poor a student. After the death of his father, at an early age he was sent off to his uncle with the hope being that a stricter daily regime would toughen him up and install some discipline this wayward child. However, in spite of his family’s best effort, Yared kept on falling behind and appeared destined to fail.

One day, Yared, just barely a tween, so thoroughly disappointed with his lack of success in life, left Aksum and headed to Medebay Zana. Tired of schooling and defeated, he felt resigned to live a more quotidian life elsewhere — anywhere but with his authoritative uncle.

Yared in a piece of 15th century Ethiopian sacred art. (CC) Wikimedia Commons.

One day, on his way there, in Maikrah, a heavy rain started to pour over his head. Forced to take shelter under a tree, there Yared noticed something that would forever change his life: an ant. This small ant trying to climb the tree with the load of a seed, kept trying and failing miserably. One try, fail. Two tries, fail. Three, four, five, six tries, fail. Then, on the seventh try, success. Deeply moved by its determination Yared pondered his own lack of patience and resolve.

Masinqo, an one-string fiddle-like Ethiopian instrument. (CC) Wikimedia Commons.

Feeling inspired, Yared went back home, paid more mind to his uncle, and renewed his studies with a fervor no one thought resided in him. By the age of 14, he had become so advanced in devotional studies, from fluency in Hebrew, Greek, and Ge’ez (his native tongue) to knowledge of Biblical scholarship, he was tasked to replace his own uncle as deacon after he passed away shortly thereafter. What happens next is part history, apocrypha, and myth.

Various versions of the popular story coalesce into one central vision. One day, from above, descended three birds that would teach Yared the music of heaven in Ge’ez. So beautiful and heartfelt was their bird song, that Yared immersed himself in their singing for hours. Somewhere in time, this immersion turned into a new dramatic apparition.

Kirar 5-string instrument. (CC) by leantan at Flickr,

This vision presented to him sights and sounds of angels singing songs of praise through instruments he’d never heard used in that context. Musical instruments like washint (a flute-like instrument), sistra (an ancestor to our tambourine), masinqo (an ancestor to our common violin), drums, kirar (a 5-string banjo-like instrument), and mekwemia (the tau-cross staff) were all part of this heavenly ensemble. As he tried to remember these songs he’d never heard before, he snapped back into the earthly realm.

Resolute to recapture that same feeling again, Yared tasked himself with creating some of the first-ever composed music in history. In order to recreate this revelatory music that entranced him then, he’d have to use those same instruments to do so and make sure that message could be conveyed long after he wrote it. Once he could create this kind of music, he would be able to unite a country with a plethora of languages and customs under one tradition: music.

THE GIFT

In the course of the next decade, as Yared’s musical practice became more devotional, he happened to strike up a friendship with the Aksumite emperor of the time, Gabra Masqal. A spirited patron of the arts, Gabra would commission Yared to introduce his chants and dance to all the churches. Yared in turn, would through the course of his life, focus on creating five volumes of chants.

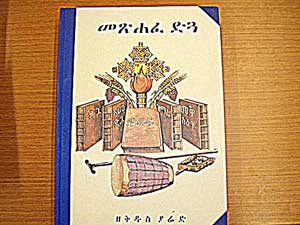

The Book of Digua by Yared. (cc) Tadias Online.

These chants, combined with choreography and instrumentation, some forming the basis for writings like The Book of Digua or the The Book of Meraf, could be used by anyone to easily relate a certain sacred day, a specific season, or an esoteric emotion through song.

Watch Abebe Birhane accompanied by traditional instruments in a rousing rendition of “Sedel New Angetwa”:

Using three musical scales he created, the kegnitoch, symbolizing the Holy Trinity, Yared was able to create a system of symbols (10 in total, to correspond with the 10 commandments and strings on a harp) that could now be used to convey arrangements for his chants. Signs that could easily convey pitch fluctuation, tempo, stresses, dynamics and more were being put on paper. These notations allowed what was once an oral music tradition to remain eternal as long as someone could understand the score.

As Yared progressed in life, he introduced the usage of the tau-cross staff to lead or conduct (an idea that hadn’t existed before) “scores.” In doing so, he kept laying further groundwork which would keep Ethiopian music and its compositional ideas living as a tradition that could span thousands of years beyond his death and canonization.

When he retreated to a solitary life in the mountainous Highlands, with birds in hand, to finish writing his final pieces, little did he suspect how far his legacy would continue.

It’s something that quite few would come to understand as fully as Mulatu Astatke. By synthesizing the teachings of Yared with his own more modern history, he stood to stoke new visions…

My top-10 list of Ethio-Jazz releases

Main image photo credit: Andy Newcombe, via Wikimedia Commons.

Ethio-Jazz Playlist

Ethio-Jazz Playlist

Leave a Reply