The Musical Almanac is an ongoing series highlighting musical styles or genres from around the world. Today, we focus on this unique style from Japan: City-Pop.

Sometimes the barrier of language can be so high as to render history muted. Most people now have the luxury of being able to decipher what exactly J-Pop is or who some of the main players in the genre are. But put yourself in a time before the internet existed, when Japan was trying to stake out its own musical place in the world. This is some of our lost history that I’ll try to highlight today.

When younger generations rise to enjoy the freedom they couldn’t afford before, wonderful, unique things are bound to be created. From the city to the beach, all of this scenery would help inform a whole bevy of influences that would help form City-Pop as its own unique thing. Japanese Boogie, J-Funk, Techno Pop, New Music, are all some ways to describe it, but I’d wager, by doing so, we’re missing the bigger picture. It doesn’t help that most, if not all, of these artists to this day haven’t had their records released in the United States. Luckily for us, it’s an image and a history that’s infinitely interesting to rediscover and unravel.

So, let’s do that today…

First Light

In 1980, somewhere on Saipan’s beach shore stands one Tatsuro Yamashita knee-deep in its waters. They may not know it, but whoever Maxell hired on that fateful day was capturing a piece of history. Set aside that this would be the first and only footage we’d ever see of him, no, what’s important is that on this golden hour Tatsu was pointing to the rise of a new power, one only punctuated by the sun rising on the shore he was standing in. On these same shores, just one generation removed from his own, an older generation had lost its last line of defense towards a justifiably untenable future. However, now, here in the Marianas, Tatsu was at the nexus of a sea change, one decidedly earned.

Maxell’s commercial featuring Tatsuro yamashita

Promoting Maxell’s release of his cassette single for “Ride on Time”, it’s this song that pointed towards the future. Mixing tropical soul, funk, and jazz, its massive success — a first for a new type of music he was helping create — was the realization of the power of a new type of freedom. You see, it’s his music that would play perfectly for a new generation of Japanese trying to get rid of some of the baggage from their past. Popping in his single to a Japanese-made car with a Japanese-made car stereo, all products of hard-earned sacrifices, meant acceptance of a new lifestyle. While Big City living provides many of the creature comforts a new, modern, upwardly moving society needs, it doesn’t provide everything. When one needed to unwind and truly enjoy the fruits of day-to-day drudgery, nothing would ever replace the providence of leisure and a soundtrack to back it.

Tropical Dandy

It was Tatsu’s music that luxuriated in this new feeling. For countless years, first as a member of the band Sugar Babe, then as a solo artist, he had experienced little success with the kind of music he was creating. Running counter to a lot of the other rock bands of its day, in the mid-’70s he had experimented with influences others seemed to frown upon. West Coast sunshine pop, doo-wop, soul, jazz, and R&B spoke more to him than blues-rock or folk. This tropical sound, filtered through these influences, spoke more to the Japanese island experience than all the sonic placement of Western music in neighborhoods surrounding suburbia. Grooving when others rocked, playing 9th, 7th, or Flat-5th chords on his guitar when others powered through theirs noodles-ly, his music stood in bright contrast to the increasingly dour music others in Japan were creating. Marginalized by their record label and booed while performing, they dissolved and went their separate ways, accepting that audiences weren’t receptive of what they were creating.

The Embryonic City-Pop of Happy End, “Natsu Nandesu”/On a Midsummer Day:

Tatsu himself though refused to give up. Going solo, he took cues from other, similarly disappointed artists like Haruomi Hosono and Shigeru Shizuki who had left their own pioneering band Happy End to pursue this third way, even if the fruits of their efforts weren’t being exactly rewarded then. These artists dove deeply into the kind of music that they’d heard broadcasting through American military radio or had received copies of from visiting Hawaiian or Californian family. Exotica, music with Tropical motives (Jazz-Fusion, Bossa Nova, and Latin styles), all of these appealed to them in ways that other styles hadn’t.

Haruomi Hosono’s Tin Pan Alley

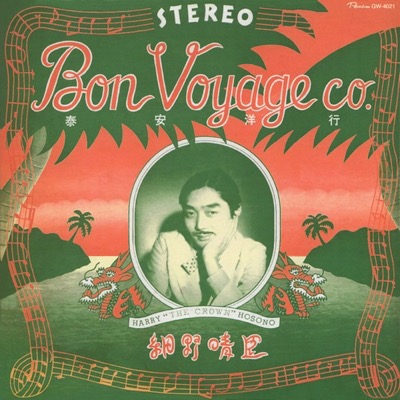

For some, like Haruomi they’d adopt personas toying with Tropical Dandyism, making music that accepted, glorified, and amplified the breezy music from America’s own tropical coasts. Ideas of artwork, fashion, and technology moving in tandem into this new niche no one had thought fit to explore.

A Selection of City-POP Artwork

Tatsu through albums like Spacy (1977) or Go Ahead (1978), and Haruomi through ones like Bon Voyage Co. (1976) or Paraiso (1978), exemplified experimental ideas interested in mixing newfangled synthesizers with decidedly skewed pop and soul music. Although such albums wouldn’t be popular, they were more important, in a different way. These albums were presenting a unified movement that allowed other artists to have somewhere to fold their music into. Listening to Ryuichi Sakamoto’s tropical soul keyboard work on Spacy is all one needs to hear to understand the parallels in the equally challenging tropical pop arrangements backing Harry in Paraiso, as the Yellow Magic Band. It’s the separation between these styles that was only a small hop, skip, and a jump away. But, like everything has shown, critical success doesn’t always breed personal success.

Right On Time

In 1979, by the time Tatsu had started to work on his album Ride on Time, the financial failure of his previous records was getting to him. Pouring all his work and money on crafting his kind of music had left him on a financial island without much to show for it. Traveling to the U.S., much like Haruomi, he had been trying desperately to find musicians who could perform with vigor the kind of music he was aiming to make. Having released an album, Moonglow, to appease some of the growing disco scene, in a way he had bended enough to have some solvency for his last push. Finally finding suitable musicians in his homeland he returned, to begin work on Ride on Time. His thought at that time was to title the song as an ironic eulogy to what he thought had been his luck. However, as the single became increasingly more and more popular, exploding once Maxell picked it to soundtrack this new kind of portable music format (the cassette tape), the title now fit more an affirmation of what Tatsu had finally hit on: City-Pop.

A selection of City-pop instruments

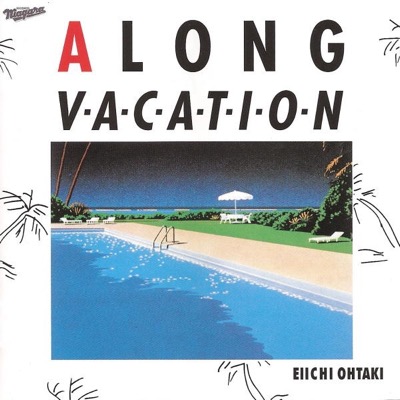

It was this massive hit that would lift all these other boats. All of this, the music, the imagery, would finally crest through leagues of new musicians lapping on the surf he’d ridden on. 1981 can be seen as the turning point. This is the year when Eiichi Ohtaki’s, another ex-member of popular rock band Happy End, released his own Japanese-tinted Blue-Eyed Soul masterpiece A Long Vacation. Featuring the trailblazing coastal Art-Pop artwork of Hiroshi Nagai, Eiichi validated Tatsu’s work on Ride on Time by presenting his own populist take on this style. It was Eiichi’s album that joined Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Solid State Survivor as harbingers of entirely new, forward-thinking Japanese musical styles. All of this to the tune of upwards of 70 million copies sold.

Eiichi Ohtaki’s “雨のウェンズデイ”

When For You was introduced in 1982, in this author’s opinion Tatsu’s masterpiece, it displayed in full splendor all the wondrous styles and themes of City-Pop as a genre, something many would attempt to flesh out further in the future. Matching Eiiichi’s sales, and more importantly taking advantage of a boom in a new industry, its Sun-basking sound fit a whole new music market ready to take in the sounds of summer, whether by boom box or on a Walkman…now, cars be damned.

Released in the dead of winter, and maintaining its popularity far into that summer, and the succeeding seasons, something sparkling about this sound hinted at some rising popularity this kind of music still had ways to explore. That’s where we’ll try to turn our gaze below. It’s what solidified that Japan, outside of rock, pop idol, and Enka, had something else of its own to offer, something we now call J-Pop.

The Big Wave

Around 1978 CBS/Sony had started to put stock in something it rarely had before. This joint venture between an American and Japanese company was opening itself to ideas that ran counter to a prevailing business culture. For decades Japan remained openly hostile and protective of its economy. Such protectionism extended to Japanese culture. Although they didn’t see any problem in presenting American artists to Japanese audiences, they rarely saw any incentive to invest in musicians who strayed from established Rock, Folk, or Enka genres; all genres deemed to be globalized enough to pass off as not deviating too much from existing Japanese influences. However, to promote artists that dabbled in R&B styles would take something else altogether.

Makoto matsushita performing “Love Was really gone”

This new kind of music, that was decidedly more flagrant in its Western influence, particularly with the type of music you’d hear in the urban streets of America or in its growing, upwardly mobile coastal cities, was revolutionary. How so? In essence, it was because of the challenge it presented to the Japanese conservative orthodoxy floating around. For years, when Japan slowly started to ramp up its economy, countless songs were written in emotional styles that bespoke of a struggle, whether spiritual or economic, to uplift the community against or in spite of some other. Eventually in the mid ’70s, rock and folk-influenced artists like Happy End, Yōsui Inoue, or the Southern All Stars started introduce deviations from these ideas. As the economy grew, and people’s spirits were enlivened alongside their wallets, the marketplace for even further ideas was ripe. Leisure, rather than being frowned upon, was openly flaunted as something to aspire for.

Breaking Blue

Where does Sony come in? Well they did so by acknowledging this shift. Knowing that there was this prospectively large base of young consumers they had to play to what or where they were going to listen to new Japanese music. What better way to get the same audience that would buy Sony car stereos, headphones, and Walkmans (all relatively new inventions of the late ’70s) than by producing their own content to play in them?

Now, artists were talking of personal rather than communal struggles, and dropping in English vocals when a Japanese one wouldn’t fit musically. Now that the economy was on such an upward trajectory, a third way was opening up for musicians who had been champing at the bit to challenge staid social customs and ideas. They wanted music that could speak to their own generation. In the past, their songs might have been dominated by lyrics speaking of dreams of the countryside or longing for a simpler life. Now that life presented them this appealing alternative, they needed something else. Now, with artists like Tatsuro Yamashita, Haruomi Hosono (future-Yellow Magic Orchestra), or Momoko Kikuchi, they had a style of music that spoke enthusiastically about big city living and, when needed, could provide a bumpin’ soundtrack to beachside weekend getaways.

TOSHIKI KADOMATSU’S “52nd Street”

Content with booming dance rhythms and uptempo music that would sound perfectly on it. The ten year anniversary of the Sony’s partnership with American-owned CBS gave them an excuse to present some kind of unified vision of what this was. Some of the first albums CBS/Sony released were compilation albums of sorts. Albums titled Pacific, The Aegean Sea or New York were the most promoted. All of these were becoming immensely popular, and coastal music-themed releases featuring covers adorned with corresponding imagery were evoking this new kind of weekend living.

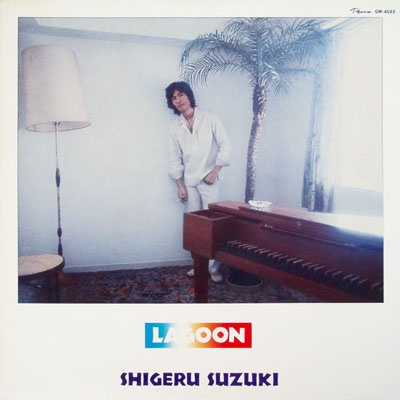

The interesting thing is that the Japanese musicians who played on them, many who had in earlier years been ostracized for not sounding Japanese enough, finally had an outlet for their own American-influenced R&B, jazz-fusion, and funk music that they tried desperately before to get heard on the radio. Music they had been dissuaded from performing…let alone have a label backing them up. Imagine Haruomi Hosono, Tatsuro Yamashita, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and Shigeru Suzuki creating their own idea of coastal music? That’s what you’d hear here. Astoundingly, they’d use such free-flowing recording sessions as ciphers to push their own ideas forward. That’s what you’d hear in City-Pop’s golden era. Either through subsidiary record labels like Sony’s own Niagara or in others like AIR, or RCA, Alfa, or Victor, the industry as a whole added some much-needed financial muscle into whatever direction these new artists headed towards to.

Big In Japan

While in America, AOR, disco, or blue-eyed soul, had been somehow thought of as gentrified versions of “black music,” in Japan audiences deemed it differently. For them, such music was part of separate thought process. In these artists, they were seeing how someone of a different skin color could successfully create music that exists outside of increasingly segregated genre labels. Seeing on album covers and hearing artists like the Ned Dohenys, Darryl Halls, and Steve Millers of the world, guys who weren’t exactly the same skin color as R&B artists like Marvin, Stevie, Curtis, or Earth Wind and Fire, and with similar artistic tastes, allowed them to step up to any record label and say: if a guy like Ned can do it, and be successful, why can’t we get the same support? They all loved R&B music just as much, but had always run into record labels that could easily justify not backing someone like their own Toshiki Kadomatsu, regardless of how unique his kind of soul was.

The official video for Piper’s “Sunshine kiz”

At the start of the ’80s, coinciding with a booming Japanese car stereo industry, justifying such explosive audio systems required music that positively beamed from their car decks. Starting with the seeds of early work by artists like Haruomi Hosono and Sugar Babe, (who had taken cues from Hawaiian or ex-pat Japanese living in California who favored groovier music) advances in technology and increased label budgets allowed these same artists to create West Coast masterpieces they only could have dreamt about before.

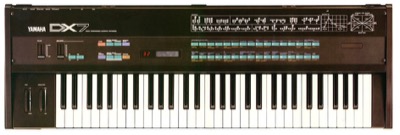

Its this shift you can hear and see clearly in all the tools they had at their disposal to present some kind of unified movement. That’s where the term itself, City-Pop, makes perfect sense. You hear it in the use of Linndrums for percussion, or in using polysynths like the Yamaha DX7, Roland Juno-60, ARP Quadra, Moog Polymoog, and Oberheim OB-8 (to name a few). The music speaks less of a fight on caring whether analog is better than digital, or vice versa, and more of a struggle whether the arrangement can be curated as meticulously as possible. If a session musician wasn’t up to snuff, a Roland MC-8 or Yamaha QX-1 sequencer could (through tireless work) replace him. Sophistication, one of the words frowned upon in other genres, is key to its appeal.

Weekend Flight to the Sun

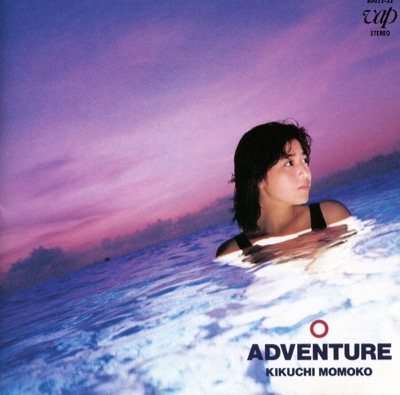

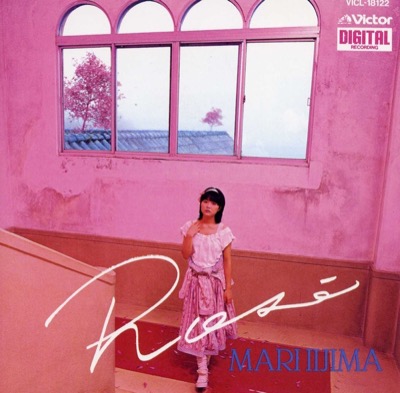

Unsurprisingly, dig through enough discography credits and you’ll be surprised how many of the greatest City-Pop artists would play on each others’ records. Dig even deeper, and you’ll peel layers where supposedly “serious” artists like Ryuichi Sakamoto, can produce challenging electro-pop but not the kind you hear promoted in supposedly “serious” circles. It’s their loss at never hearing Ryuichi’s brilliant production work for Mari Iijima’s Rosé, but that’s what the aim of this post is to do. My aim is to, in a small way, shine a light on a genre that paved the way for exactly what didn’t exist then: J-Pop. Witnessing the uber-talented Momoko, who grooved far heavier than her sweet voice and appearance belied, brings to mind how not far off she was from future, genre-bending J-Pop mega-starlets.

MOMOKO KIKUCHI’S “BLIND CURVE”

When America’s West Coast Pop/R&B seemed to peter out around the early ’80s, it’s in those same early days of City-Pop that Eiichi Otaki’s A Long Vacation, and a year later Tatsuro Yamashita’s For You, had began their ascent to their own place on the horizon. Stylistically and sonically, those two albums would present the coordinates to a peak hour, before the good times ended and bubbles burst everywhere in the early ’90s. Only recently, artists like Hitomitoi, Greeen Linez, or Junk Fujiyama, and not to discount the whole Vaporwave genre, have started to look back to this original time for inspiration.

Of course, this wouldn’t be the first time artists had done so. Before them other artists like Cornelius, Flipper’s Guitar, and the Pizzicato Five, all Shibuya-Kei scene artists, had done so. They form one of many building blocks that piece together the beguiling Fishmans’ Uchu Nippon Setagaya. Although summer isn’t quite so endless, at least for a bit, one can bask in that sun rising again…

| Name | Album | Track Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Momoko Kikuchi | ADVENTURE (1986) | OVERTURE |

| 2. Momoko Kikuchi | ADVENTURE (1986) | ADVENTURE |

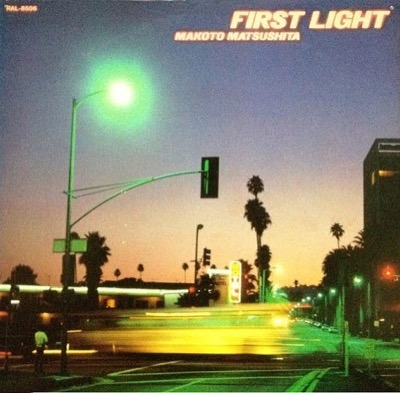

| 3. Makoto Matsushita | FIRST LIGHT (1981) | FIRST LIGHT |

| 4. Piper | Summer Breeze (1983) | Starlight Love |

| 5. Haruomi Hosono and the Yellow Magic Band | Paraiso (1978) | Femme Fatale |

| 6. Kimiko Kasai | Kimiko (1982) | Steppin’ Outside Tonight |

| 7. Kanako Wada | KANA (1988) | SUNDAY BRUNCH |

| 8. Toshiki Kadomatsu | AFTER 5 CLASH (1984) | If You… |

| 9. Akemi Ishii | Mona Lisa (1986) | インスピレーションの夜 / Night of Inspiration |

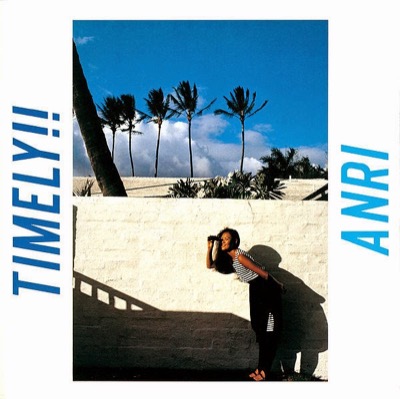

| 10. Anri | Heaven Beach (1982) | 二番目のaffair / The Second Affair |

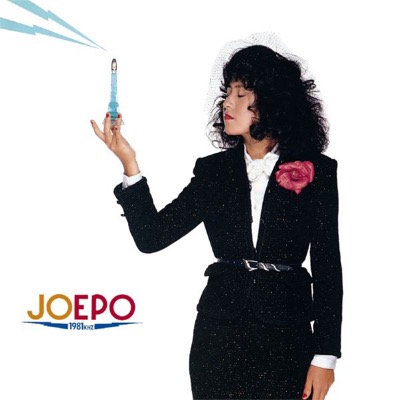

| 11. Taeko Onuki | Aventure (1981) | チャンス / Opportunity |

| 12. Eiichi Ohtaki | A Long Vacation (1981) | 雨のウエンズデイ/ Rain Wednesday |

| 13. Ryuichi Sakamoto | Summer Nerves (1981) | Summer Nerves |

| 14. EPO | Down Town (1980) | Down Town |

| 15. Tatsuro Yamashita | Big Wave (1984) | Magic Ways |

| 16. Tatsuro Yamashita | FOR YOU (1982) | LOVE TALKIN’ (Honey It’s You) |

| 17. Mari Iijima | Rose (1983) | ひみつの扉 / Secret Door |

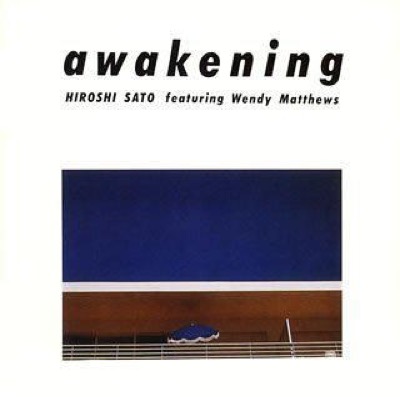

| 18. Hiroshi Sato | Awakening (1982) | Say Goodbye |

| 19. Minako Yoshida | Monochrome (1980) | Tornado |

| 20. CBS/SONY Sound Image Series | New York (1980) | New York Subway |

| 21. Minako Yoshida | Monochrome (1980) | Midnight Driver |

| 22. Yellow Magic Orchestra | Service (1983) | Shadows on the Ground |

| 23. Toshiki Kadomatsu | SEA IS A LADY (1987) | Way To the Shore “Eri” |

| 24. Seaside Lovers | Memories in Beach House (1983) | Melting Blue |

| 25. Hiroshi Sato | Orient (1979) | Kalimba Night |

| 26. Piper | Summer Breeze (1983) | Gentle Shower |

| 27. Mari Iijima | Rose (1983) | おでこのkiss /Kiss on the Forehead |

| 28. Hiroshi Sato | Awakening (1982) | Blue and Moody Music |

| 29. Sugar Babe | Songs (1975) | Sun Gone By |

| Artist | Album | Track Name |