For me, there are certain albums that are tied to certain vistas and experiences. Not too long ago, I had the pleasure of visiting the America’s largest railway museum in Union, Illinois. Nostalgic for a time when you could travel the world at a pace more conducive to reflection, I set my sights. For half the journey, after you escaped the initial 45-minute reach of Chicago’s suburban sprawl, you’re treated to a different way of living. The stretching two-lane highways, rolling hills, and prairies of Illinois set the scene for moments most never forget. It’s in those moments, free from distraction, filled with relaxed conversations, silent acknowledgements, and fleeting recollections that stay with you. It’s a communal thought. Although, I may not be a country boy, out here, in the open road, I feel there’s some kind of deep connection to this scene that anyone can share. Back then, playing Ronnie Lane’s One for the Road made the best of sense.

You see, Ronnie was never like most classic rockers. To virgin ears what you hear here is not the woozy Toontown Psychedelia of early Small Faces. At a gut-level, this isn’t the sound of classic hard-nosed rock in the style of Rod Stewart and The Faces. No, this is something different. These music roots were in country, not in the American sense, but from his own backyard in England, and with stems far more genteel than anything he’d ever make elsewhere. Back in 1975, this made the best of sense when you hear it in the truly powerful recordings he made.

Ooh La La

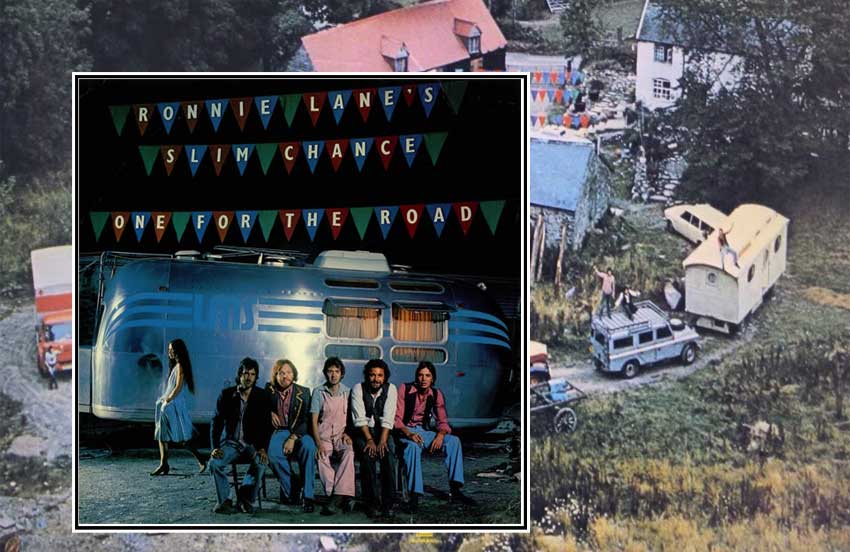

You see, just three years before, Ronnie was living the furthest away from the Rock-n-Roll lifestyle as you can imagine. While the rest of The Faces were using their millions to buy lavish lofts and expensive things, all he did was spend his money on a huge, old Land Rover he could use to drive through the English countryside. The only other big purchase he ever made at the time was to buy one of the first truly mobile recording studios, housed in an Airstream trailer somewhere in London. In love with the truly free-spirited Kate McKinnerney, and with baby in tow, he was slowly turning away from the life of a Mod god, into the life of a Traveller Gypsy. A lifestyle more in tune with starting a farm and roaming the land with his buddies, than whatever was the normal alternative.

Enrolling in agricultural school, rightfully falling in love with the American country-folk music of Derroll Addams (the second famous English musician to do so), following idealized notions of homesteading, communal performance and much more, he was living part-and-parcel the dream both Kate and he we fashioning in a way. After the dissolution of The Faces, seeking to get away from the music industry and the city, he emptied what little savings he had left into a large farmhouse in Wales. Trying to reconnect with that spirit of warmth he was after, those early years were tough for him post-Faces. Destitute and nearly homeless, he had taken to fishing by his farm to keep a certain dream alive, let alone sustain himself.

It’s a case of history repeating itself; Rod Stewart had abandoned Ronnie. Much like Steve Marriott, had abandoned his Majic Mijit friend to pursue heavy British blues, now Rod Stewart had enough of Ronnie trying to place his own, different stamp on increasingly his music. “Ooh La La“, written by Ronnie, perhaps showed a winking knowing nod to a realization he had to deal with, if other Faces songs he’d written like “Glad and Sorry” hadn’t made the point already. If, he was going to continue making music he’d had to do it on his own. Maybe something he wasn’t entirely ready for. One day, something struck him. On that day a friend of his came by the farm and they struck up a nice little tune that pointed exactly in the direction Ronnie wanted to take for his own music.

“How Come,” recorded somewhere in the fields of Ronnie’s farm was a whole new something else. Mixing Irish folk, Vaudeville, and Americana, with truly, intrinsically “English” music (like skiffle or jig), it was his distinct idea of a new kind of country-rock music. When he rounded up a band full of sympathetic musicians, ones he’d dub his Slim Chance Band, they’d somehow make this track a hit single. Now, it’s easy to see why if America had its The Band, England quite possibly, had it’s own Slim Chance. This track that gave them the allowance to perform in front of a large TV audience, to the giddy delight of one Stevie Wonder sitting/air playing it off stage, and let Ronnie land his first record deal.

As Slim Chance attempted to parry off this success, and redouble it with the far more brilliant and unique “The Poacher“, once again fate threatened to derail Lane’s career, if not send it careening off. The day they were set to perform it live at Top of the Pops, a cameramen’s strike forced them to cancel their performance. With the debut record languishing with little promotion and hardly any radio play, now they had to find a way to keep the journey going. That’s when Kate struck around with this fantastical idea: a gypsy caravan musical tour.

The Passing Show

1973’s Anymore for Anymore, recorded outdoors via Ronnie’s Mobile Studio, although critically loved, became critically forgotten, and was met with pitiful sales. So, strapped for cash to record a second album, they did what would become a common theme for them; they started from square one. Sometime, in 1974, Ronnie once again took nearly all of his earnings and placed them into something his wandering muse asked of him. In this case, it was buying an old, dilapidated circus and use it to create a new kind of touring revue. Hiring an ex-lion tamer, all of the crew and band, in between taking turns toiling at his farm, and rehearsing, would work on sprucing up this musical caravan. Once, fixed (to a point), they took the show on the road (albeit at a top speed of 15 mph, the max the campers could handle) and would head out anywhere they were able to pitch a tent.

If success and failure could be measured in monetary terms, this tour was a failure. If success and failure could be measured in immaterial terms, this tour was a different kind of resounding success. Whether performing to crowds measuring the number of digits in two fists, or rivaling the amount of sheep they could ward off, the tour (all 23 shows) fomented all sorts of radical ideas that other bands would later run with. They weren’t the best at promoting themselves, drafting and giving out flyers just a day before a tour, but these ideas of mobile performances outside the classic concert halls were revolutionary. For the band and Ronnie, The Passing Show (as it was dubbed then) began a new phase for them. Recording over the master tapes from their debut album, they started work on their second a self-titled affair, Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance.

By then, this record full of perfectly realized, deeply human, unpretentious songs (warts and all) like “Stone“, “Anniversary“, and “Tin and Tambourine“, all should’a-been hits, came joined at the hip to an album title cheekily acknowledging how much chance anyone would give them to succeed. All of this, would be for nothing, if despite all of this failure, there wouldn’t be something else in spirit that would lift up Ronnie’s masterwork: One for the Road.

Before Pete Townshend tried desperately to help his friend out monetarily by recording Rough Mix with him, and before he discovered he’d have to struggle for the rest of his life with Multiple Sclerosis, there was this genuinely humble testament to our open roads; whatever they may be or wherever they may lead. In 1976, Ronnie would once again wipe his previous recording master tapes and start anew. Its this time that he’d take his unique mix of music to its ultimate form.

When I hear the perfect Country-Rock of “32nd Street,” my mind starts its journey. Peaceful in all those perfect places, and rousing in the justified ones, this is the mood setter that gets you started for the rest of the trip. New-Orleans Zydeco via the Welsh mosslands of “Snake” gives way to Spanish-tinged neo-folk tracks like “Burnin’ Summer,” and then they clear into the full-throated, quotidian humanism that is the title track. Its this title track, full of stunning Anglicana (if I can coin such a term), swaying alongside equally stunning lyrics that stick with you for life. These are the words and music that stick with you in the best moments in life you’ll encounter. These are the closer treasures that you wish to share with others. It’s all the good news, for all the good times, however simple they may be.

Schlepping alongside me, to a simple place, to experience simple things, things that stick with you far longer than far more intricate things ever did, there were inkling of things I’d never imagine, things that will never sound as fully realized as it did when I heard “Harvest Home” play on the car stereo then. When I heard it there, playing somewhere in between the city and that destination, as the pastorale set in, as conversation silenced for a bit, and this tender music earned the respect it deserved, in the end, it was in it that I remembered something fully realized. By the time, I got to “G’Morning” I was having communion with someone I never knew, and maybe, quite possibly, dreaming the same dreams. Perhaps one day, I can make music as life-affirming as Ronnie’s, that moves someone in the same moment in life. It’s all a pipe dream, and who knows if my dream is better than his, but this all made so much sense then. However, now, if ever I chose to do so, now I know there’s a perfect soundtrack to get me there.

- Note: Due to the machinations of our record industry, Ronnie’s work, especially One For the Road, has never been issued or reissued in the U.S. If you happen to find a copy of any of his first albums, skip a lunch or two, and buy it there on the spot. What you’re holding is something special!

Follow our Music Picks on Spotify

Leave a Reply