Classic, glassy, spring reverb. It’s a snapshot into the past of guitar tone. Mental images of Telecasters through a spring reverb-equipped amplifier in the hands of Dick Dale or George Harrison dance through your mind any time you hear it. But for most players, classic spring reverb tanks just aren’t practical in the modern age. That’s where the Belton Brick comes in. The Belton Brick isn’t just a chip in your EarthQuaker Devices Ghost Echo or Levitation reverb pedals, it’s a genius way of attaining those gorgeous spring reverb tones of the past, digitally. The fascinating history and operation of the Belton Brick may not be widely known, but it’s vital for understanding the last few decades of reverberated guitar tones.

The Belton Begins

Spring reverb made its debut inside Hammond organs of the 1930s. These organs contained a large mechanical reverb tank emulating what it might sound like to play the organ in a church hall or cathedral, but within the walls of your own living room. A few decades later this technology was slimmed down to more portable designs and made its way into guitar amplifiers of the ’60s and ’70s. Popular in surf, country, and rock music of the day, spring reverb and the tones around it laid the groundwork for an entire generation of guitarists while humbly attempting to emulate the sound of a big room.

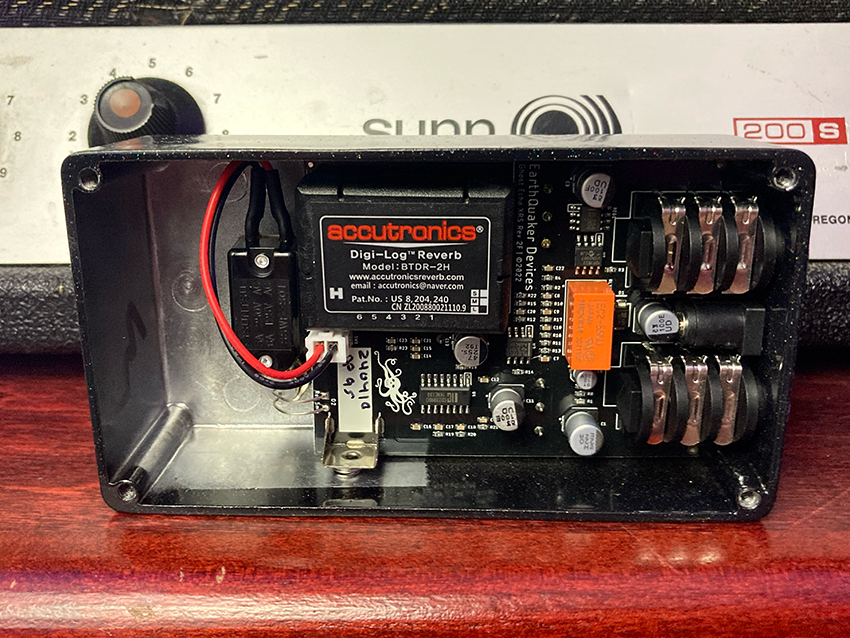

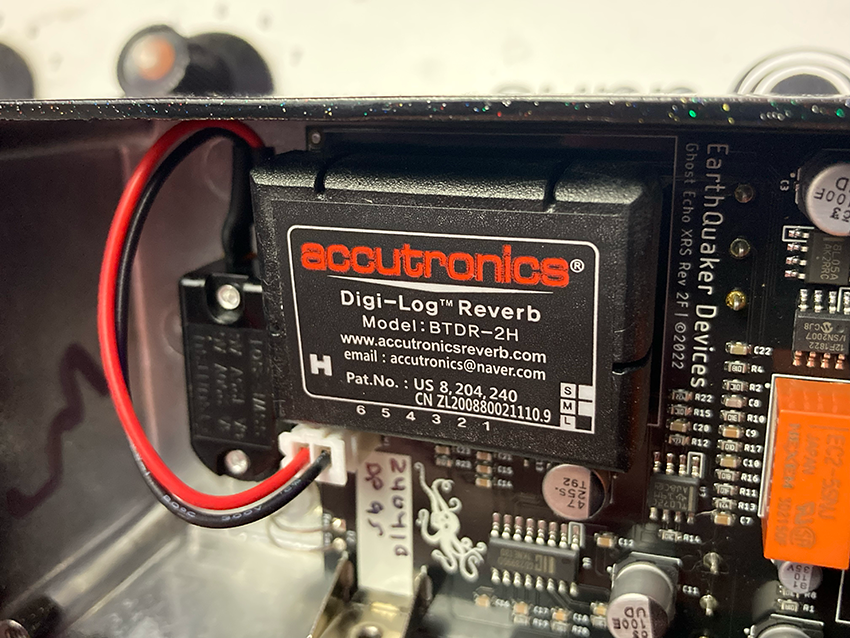

Fast forward to 2007, Brian Neunaber (of Neunaber pedals) patented an apparatus and method for artificial reverberation, which would come to be know as the Accu-Bell BTDR Digi-log. Soon after, the module was given the shorthand name “The Belton Brick.”

The patent breaks down the invention’s intention as simulating acoustic reverberation by employing multiple delay lines to be configured in an algorithm to emulate the effect of a spring reverb. In essence, the Belton Brick uses a series of cascading delay chips to accomplish this effect. This is done by using three stacked PT2399 delay chips, which alone is used in a variety of digital delay pedals. The PT2399 is an analog-voiced delay chip that’s fully digital. When pushed to its maximum delay time (around 340ms) the PT2399 brings out a lo-fi, static tone.

It’s important to mention that Neunaber’s patent makes note of the inexpensive nature of using the Belton Brick. Everything around the Belton Brick can be fully analog and inexpensive. The algorithms are handled by the Belton Brick, which include delay lines, while the circuitry around it handles all filtering, summation, feedback, and gain, making it incredibly versatile and a low-cost option for any pedal builder.

How Does It Sound?

The Belton Brick emulates a spring reverb effect digitally, and has gained notoriety for its clean operation and ease of use. Spring reverbs, specifically Fender 3-spring units, feature delay times of around 30-40ms, and this is the exact specification and reverb unit that the Belton Brick is based on. Though you can change the analog circuitry around the Brick, you’ll always feature delays at this same length because of the digital nature of the Brick.

Some describe the tone as “metallic” or “glassy,” which is how the original Fender units were described. In recent times, pedal builders have cut off some treble to get a more “cave-like” or dark sound out of their Belton Brick-powered pedals.

The Belton Brick re-imagined and re-tooled the world of spring reverb. It allowed a generation of players to experience glassy, tone-rich spring reverb without breaking the bank and has inspired musicians since Brian Neunaber’s 2007 patent.

Leave a Reply