LEGENDS: WENDY CARLOS

What happens when science and music collide? That is the question legend Wendy Carlos has been answering for decades. The explosive spark from this intersection lit an unquenchable fire in Carlos’ heart that continues to make a lasting impact today. The history of synthesis as we know it cannot be recounted without the immense contribution of Wendy Carlos. Whether she was pushing the boundaries of electronic music, pioneering the development of new synthesis tech, blazing a trail for a new wave of film composers, or being a courageous advocate for LGBTQ+ rights and representation, Carlos was never complacent.

This legend inspired and created magnificent pieces of music that touched the ears of musicians, music geeks, and everyday film lovers! Let’s dig into where Carlos began and how she became the artistic icon we know today.

In the Beginning, There Was Carlos

Carlos grew up in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. From an early age, she was interested in both music and the sciences, writing her first composition at the age of 10 and winning the Westinghouse Science Fair (now known as Regeneron Science Talent Search) by building a computer at the age of 14. Her talents and interests continued into higher education when she attended Brown University from ’58 to ’62 for a double major in music and physics. This led to a master’s degree in composition from Columbia.

At Columbia, Carlos studied with two of the brightest minds in electronic music at the time: Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening. They all worked and studied together at the Columbia–Princeton Electronic Music Center in New York, the oldest American electronic music research center.

All of this education and interest laid the groundwork for what would become the next big step in music as we know it. While attending Columbia, Carlos attended an Audio Engineering Society show. There, she had a chance meeting that would forever change the course of electronic music.

The Spark That Lit the Flame: Bob Moog

Carlos, as an interested student and musician, couldn’t help but be curious about the Moog display at the Audio Engineering Society show. The modules were all new and on the cutting edge of electronic music tech at the time. It was here that Wendy Carlos first met Bob Moog. Carlos spoke about her experience meeting Moog, saying “He was a creative engineer who spoke music, I was a musician who spoke science. It felt like a meeting of simpatico minds.” This chance meeting blossomed into a powerful friendship and partnership.

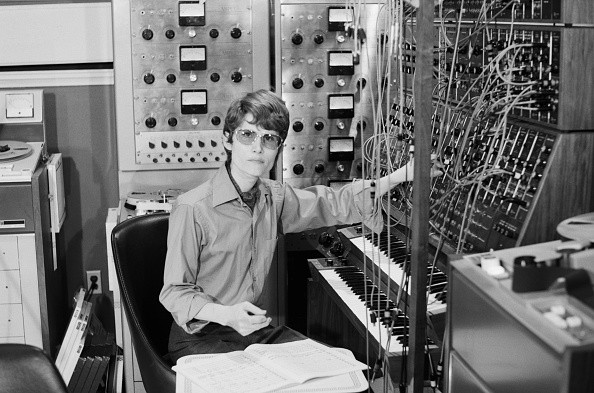

Over time, Carlos began perfecting the use of the existing Moog modular synths. In 1966, she collaborated with Moog on creating a custom system to her exact specs. This custom modular system would become the star of Carlos’ debut album, Switched-On Bach.

Ever modest, Bob always deferred on musical matters to those of us who came from that side of the art/tech equation. We, on the other hand, deferred to Bob on all engineering decisions and designs. From the beginning it was a balanced yin/yang relationship between a maker of musical tools and the artists who used those tools.

Wendy Carlos

Going For Baroque

Wendy Carlos honed the potential of her custom Moog synthesizer into a musical paintbrush capable of achieving a vast array of timbres, textures, and tones. In 1968, she released Switched-On Bach, bringing synthesis into public awareness. On the album, Carlos created electronic interpretations of famous works by Johann Sebastian Bach, tooling her synth to achieve orchestral-esque tones that highlighted the original works AND the synth.

Switched-On Bach received critical acclaim, topping the Billboard Classical Albums chart and winning three Grammy awards. Newsweek even referred to this undertaking as “plugging into the Steinway of the future.”

Before Switched on Bach, the public largely viewed the synthesizer as a mysterious device, something useful in experimental circumstances but certainly never meant to create “real” music. Carlos singlehandedly flipped this narrative upside down by showcasing just how versatile and organic synthesis could be. Luckily for the music world, she didn’t stop there.

“But What I Do I Do Because I Like to Do”

Carlos went on to collaborate with Stanley Kubrick on the 1971 cult-classic film, A Clockwork Orange. This dystopian trip of a film was devised under Kubrick’s innovative influence and deserved an equally innovative score. The score to A Clockwork Orange followed a familiar path, with Carlos again synthesizing classical pieces by Purcell, Beethoven, etc.

The real visionary feat in this score was Carlos’ use of the vocoder. Carlos implemented vocal synthesis into A Clockwork Orange which helped to push the otherworldly atmosphere over the edge. Her interpretation of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony choral movement was a particularly powerful and somewhat unsettling use of vocal synthesis that amped up the awkward tension in the film’s record store scene. This early use of the vocoder was yet another ingenious achievement for Carlos and a major help in springing the soundtrack to No. 146 on the Billboard 200 chart.

"Here's Johnny!"

In the ’70s, as Carlos continued to refine her synthesis chops, she expanded the breadth of the instrument by releasing experimental electronic albums, ambient music, and more synthesized popular pieces, including a followup release to Switched-On Bach and a double album containing all six of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos performed on synth.

This led to 1980 when Carlos and Kubrick again collaborated on an arguably even more groundbreaking film, The Shining. While much of Carlos’ music was sadly not used in the film, the pieces that were utilized are stunning. The main theme is a take on a section of “Symphonie Fantastique” by Berlioz and features her signature warm and haunting analog synth tones.

In ’82, Carlos composed the score for Disney’s Tron, her first foray into including physical instrumentation into a film score. This score is a masterclass in combining electronic and organic textures, featuring a full orchestra, choir, the famous Royal Albert Hall organ, and, of course, her analog and digital synths sitting front and center. Her classically influenced style continued to shine through in this more lighthearted and exploratory score.

A Legend of Music and Representation

While Carlos is often lauded for her momentous musical accomplishments, she has also left a prolific impact on the LGBTQ+ community. Wendy Carlos realized at a young age that she felt comfortable identifying as a woman. She has admitted to feelings of jealousy in meeting other women who had been assigned their female identity at birth. While she struggled with these feelings of gender dysphoria for most of her life, it was not until her time at Columbia University that she began to read studies and understand her valid feelings and struggles.

By the late 1960s, Carlos had begun taking hormone treatments. This began to affect her physical appearance, but as someone who was relatively unknown at the time, this did not pose any threat of scrutiny. Fast-forward to the unexpected success of Switched-On Bach and the then in-the-closet Carlos had some difficult decisions to make. This attention thrust her into the public eye for interviews and appearances. Carlos chose to hide her gender identity for some time, going so far as to wear male wigs and drawing on facial hair.

In the early ’70s, Carlos underwent gender reassignment surgery and spent a considerable amount of time laying low from the public eye. This was until she gained the confidence to speak her truth to the world in a series of interviews with Arthur Bell for Playboy magazine. To Carlos’ surprise, the public received her coming out with tolerance and mostly open arms. Carlos said that she was “concerned with liberation” and felt that sense of liberation after being honest about who she was, finally confident to be herself.

This announcement was a massive moment for other LGBTQ+ community members. At the time, discourse on gender identity was largely limited to pockets within the queer community. That being said, Carlos and others were surprised at how well this news was received. She became known as a trailblazer, opening doors for more to follow suit and giving confidence to younger community members to speak their truths as well.

The Legend Lives On

Carlos went on to further explore her interests in synthesis and classical interpretations over the years, releasing multiple solo albums like Beauty in the Beast and another edition of Switched-On Bach titled Switched-On Bach 2000, which took over a year-and-a-half to finish production. Her spirit of collaboration also flourished with appearances on films like Brand New World and, funnily enough, on collaboration with Weird Al Yankovic to create a comedic spin on Peter And the Wolf.

Carlos’ never-ending interest in the world of synthesis continues to inspire and push the musical world to this day. One cannot overstate the impact that she has had, not only on the synthesis world, but the entire realm of modern music. Without her momentous contributions to this fascinating instrument and her constant desire to innovate and explore, we may have never seen the massive expansion in musical depth that we experience today. Just remember next time you pull up an instance of Serum to thank Wendy Carlos, the Legend in whose steps we follow!

The Making of our video

Wendy Carlos was acclaimed for her unique and rich tonal palette, so it was difficult to know where to start when recreating her music. Despite this, I was able to craft many of the classic sounds heard on famous works like The Shining and A Clockwork Orange with the use of just a few analog synthesizers and pedals. In fact, it was this very same limitation of gear that led to several truly unique opportunities to shape the sounds in ways that I wouldn’t have otherwise considered.

While I don’t own a massive Moog Modular system (and chances are that very few reading this article do), have no fear. After all, this is what our Legends series is all about: getting those coveted classic tones with modern instruments and techniques. So put on a pot of coffee and follow along with this walkthrough of the recording process of our very special “Legends: Wendy Carlos” video feature.

The Gear That Made the Woman

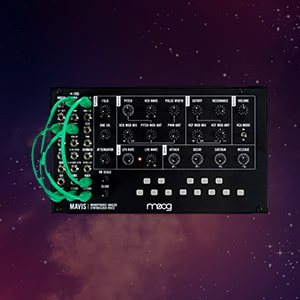

Wendy Carlos was a known proponent of using large analog synthesizers throughout her early career. The sound of analog is full, with harmonically rich oscillators and filters that respond in musical ways. As you can imagine, analog synthesizers were an important aspect of our video as well. The synths that I chose to use were the Moog Mavis, Sequential Prophet REV2 16-Voice Analog Synth, and the Waldorf Streichfett.

Though analog formed Carlos’ beginnings as an artist, her later work in the ’80s blossomed with the use of digital synthesizers. To fill this sonic void, I reached for the excellent and ever-useful Waldorf Streichfett String Synthesizer. While recording Tron, this was my digital savior for capturing all of those classic ’80s string tones.

Besides synthesizers, I was able to expand the sounds using the Warm Audio Jet Phaser pedal. This old-school, large-format phaser was bare bones and for good reason: it just sounds good no matter where you set the controls.

The process of recording used several large groupings of MIDI mapping, which can admittedly get complicated and tedious quickly. In order to manage my workflow a bit better, I used the Arturia Keystep Pro to help out. Don’t be fooled though; the Keystep’s capabilities far exceed what I used it for. It really is an incredibly useful songwriting and recording tool, with a deep interface that can prove useful for most any recording artist. More on this later.

Let’s Talk Recording…

A Clockwork Orange

Carlos’ score is absolutely chock full of spooky, eerie, and downright jarring synth tones. It’s an absolute must-listen and a masterclass in using sound to establish a mood for film. A big part of that eeriness comes from Carlos’ massive Moog Modular synthesizer. What continues to fascinate me most however, is the fact that she was recording, layering, and processing all of the tracks individually to tape. The care and manipulation of the tape and her process were vital to the sounds she was recording.

Fortunately in the modern age, we can achieve these sounds much more reasonably through digital tech. Some part of me wanted to capture the magic of Carlos’ process though, so I imposed a limitation: record each voice separately just as she had to do. What transpired was a much more purposeful project. Each track had to be dialed in and curated tonally before being recorded in order to preserve as much sound content as possible. My goal was to limit any equalization or processing in the mixing stage, if at all possible.

For A Clockwork Orange, the opening tones were done with the Sequential Prophet REV2. I tuned the main oscillator to a C note, and stacked a second oscillator tuned a half-step higher to a C# note. The synth allows for even more fine-tuning, so I pulled the tuning of the C note slightly higher than C by a few cents, and the C# note was pulled flat by a few extra cents to get the sound to be even more dissonant. That tone got in my bones by the time I recorded it!

From there, the REV2 was put to work on those low bass notes. To my ear, she was clearly trying to replicate the sound of a timpani: full, with a huge attack, but hollow sound with a moderately fast release. I used a triangle and a sawtooth wave lightly blended together to create that hollow but present tone like a timpani. The REV2 has a separate ADSR section for its LPF (Low-Pass Filter), and for its amplifier section, which is incredible for routing complex sounds. In true Wendy Carlos fashion, I exploited this feature set for our video.

For the main melody, I used the Waldorf Streichfett synth. It is based loosely on the old Solina String Ensemble synth made in 1974, so it was absolutely perfect for this application. I added a healthy amount of the onboard tremolo for the string-like vibrato, and it was nearly ready to go. I sent all of the tracks (besides the bass notes) into a Warm Audio Jet Phaser pedal for that iconic Wendy phasing that she was so fond of in the ’70s.

The Shining

Ahhh, The Shining. The famous opening credits, where the Torrance family drives up the winding road to the Overlook Hotel while Carlos’ absolutely chilling score plays, is one of the most important moments in horror movie history. But that score! That Moog tone is a staple of synthesis, but I got the tone with one small but mighty piece of gear: the Moog Mavis.

This little synth is actually a kit that you assemble yourself. You only need to assemble the outer shell and motherboard and assemble the knobs, so for those out there with no electrical prowess, it’s still an easy task to build. Once assembled, you get a VCO with pulse width modulation, an LFO, a VCA, EG section, and the legendary Moog ladder filter. Add in Moog’s first-ever analog wave-folder, and you get a ton of options for tweaking.

To get the tones heard in the film, I started with a square wave for its characteristically thick sound. I then used the pulse width knob turned just shy of all the way up, set to a 50% amount. I used no resonance, and set the ADSR as follows: 7 o’clock, 8 o’clock, 11 o’clock, and 7 o’clock respectively. The LFO was set to a square wave and timed to the original, blended in very mildly at about 15% for a gentle pitch warble.

The fun part of this song was recording it Carlos-style. On the original, the Moog Modular had multiple oscillators, while our Mavis synth has just one. I had to record each part individually, and stack them together to create a “stereo” image with a left and right panned element, repeating this process for both a lower and upper harmony. The upper harmony transitioned to a sawtooth wave though, which, when blended with the lower square wave, added some wonderful grit and edge to the tone. I manually had to tune the upper harmony exactly one octave higher than the lower harmony, which was an exercise in patience but was well worth the effort when dialed in correctly. The resulting tone was the definitive, hefty Shining sound we all know and cherish.

We can’t forget about those haunting background sounds, though. I peppered in some coos, howls, whistles, hand scrapes, and spoon/knife clangs recorded with a matched pair of AKG C414 XLII condenser mics fed through some tape saturation and delay to get it. Really fun stuff!

Tron

What makes the theme to 1982’s Tron stand out is Carlos’ incorporation of both analog and digital synthesis on top of the beautiful orchestral scores. It’s as if the old orchestral school and the new school of digital synthesizers were joining forces. It ends up being a pretty powerful soundtrack, but how could I replicate it without having a massive orchestra to record?

Well, as we talked about earlier, the beauty of synthesis is in its shaping of waveforms and envelopes which create the illusion of certain types of instruments. Carlos was well-known for her intimate knowledge of this, building custom sounds on her synths that were remarkably similar to actual instruments.

This became my new goal: recreate all of the orchestral sounds in Tron with just my synthesizers. Really understanding how your synth’s ADSR works (Attack, Decay, Sustain, Release) is essential. If you can hear what makes your favorite instruments unique, you’ll be able to recreate them with a synth. Do they have sharp attacks like a xylophone or a softer attack as heard on brass and wind instruments? Experiment.

I got to work on the string parts for Tron first. In comes the Waldorf Streichfett! I set the registration control, which acts as a really unique filter, to just in between the Viola and Violin portion. I blended in the Elec. Piano portion of the synth to give it some smoothness and adjusted the attack to be slightly longer than usual, which swelled nicely to create the illusion of the lag time between a bowed note and its bloom. The Streichfett also has a quite nice on-board reverb, which I set to about 30% to get large-hall orchestral reverb tones.

From there, the Sequential Prophet REV2 performs the rest of the instrument sounds in the video. For starters, I needed brass sounds that were genuine, so I found a factory patch called Euro Trumpet that was incredibly close. I adjusted the cutoff knob to increase some upper frequency content, and slowed the attack envelope to simulate the effect of air traveling through brass. It’s not an immediate note; the slight few millisecond delay matters here.

Once I set the envelopes, I chained several triangle wave based LFOs together to make the “vibrato” sound human and organic. The LFO rates needed a certain amount of chaos, so to speak, to feel real. Once I stacked the other three trumpet harmonies, I made a point to vary the LFO rate for each trumpet to get it to feel like a real trumpet section.

I used the same principal on the trombone section, but I programmed the powerful low-pass filter section of the REV2 to respond with more brightness as the velocity increased. As I hit the keys harder, the filter would open more to create brighter sounds, just like when you blow harder into a brass instrument. Again, these tiny details made all the difference.

I applied similar concepts to create custom sounds for oboes, flutes, and clarinets to fill out the orchestral arrangement in full. There were a lot of tracks in this recording — 47 in total! I used the Arturia Keystep Pro to help me program the MIDI note data and velocities by learning each part and then manually playing it for each harmony.

Wendy Carlos was a genius of sound design and technology with a monumental influence and presence in music history. We hope our “Legends” video does her legacy the justice that it very much deserves!