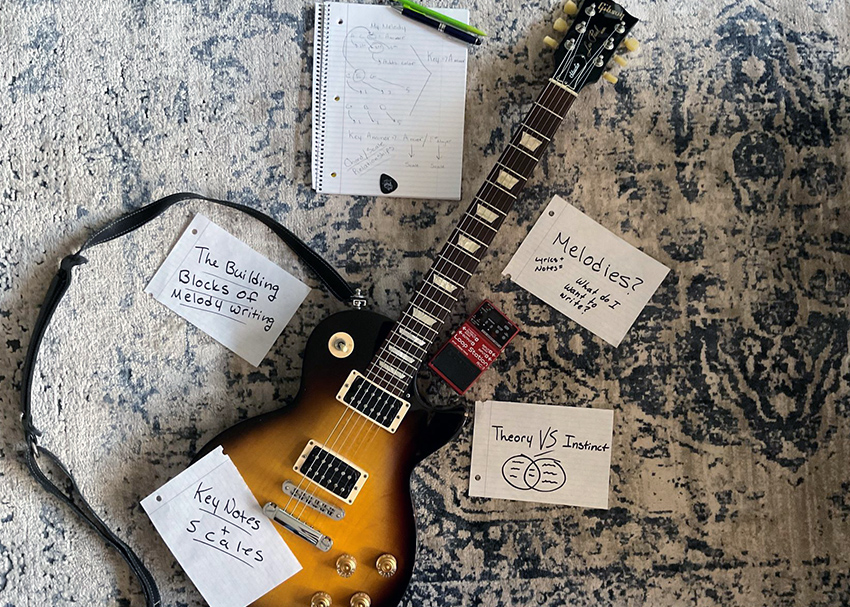

What is a melody? Chances are you already know, even if you don’t know the dictionary definition. If you have listened to music, then your instincts will tell you while you are listening, even if subconsciously. The great thing about melodies are that they can come from the voice or an instrument, making them an important part of the universal language of music. In any case, there are many approaches to creating melodies involving theory and/or your musical instincts. In this post, we explore the how to write melodies, the building blocks of melodies, and how we can use theory to enhance our instincts.

As discussed in the beginning, if you listen to music, you most likely and instinctively know what a melody is. The dictionary definition states that a melody is a collection of single notes that are musically pleasing. When we put this into the context of the music we listen to, regardless of style or genre, melodies are most often the parts we remember when we walk away. They are designed to stay with us, because by definition they are pleasing. Melodies stay with us because of how they connect what you hear with how it makes you feel. So what would be the difference between writing melodies based on instincts and writing a melody based on theory?

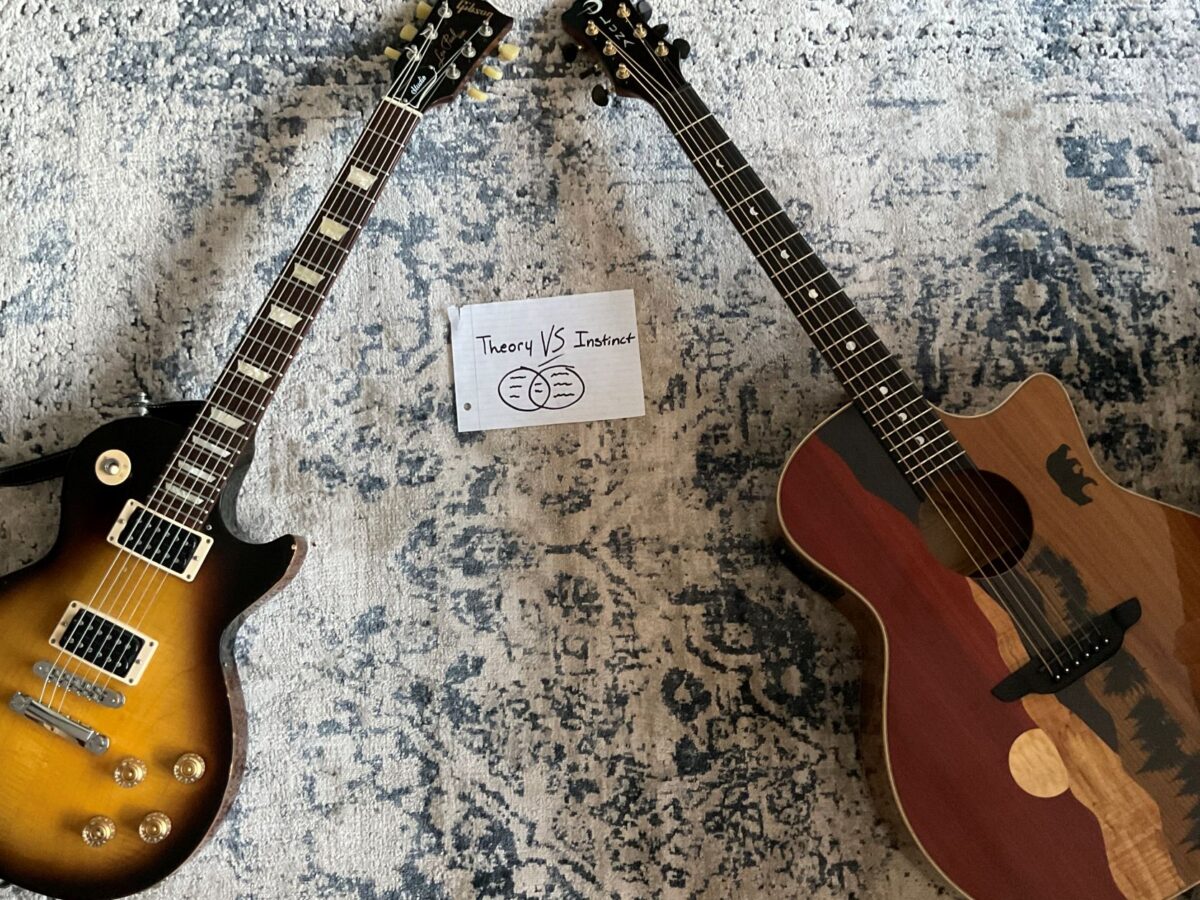

Theory Vs. Instinct

Using theory to write a melody involves making decisions based on technical knowledge rather than guesses. But does that make it better than writing from instinct? Not necessarily. Some of the best melody writers were not (arguably) always thinking about technical theory: Kurt Cobain, Billy Corgan, John Lennon, etc. But there are also those who have a great combination of instinct, feel and theory knowledge: John Mayer, Myles Kennedy, etc.

This post will work on the premise that the best way to go about writing melodies is to have a level of theory understanding that can run autonomously in the background to where it becomes second nature, or instinctual. So where do we start with this?

Applying The Building Blocks For Our Melody

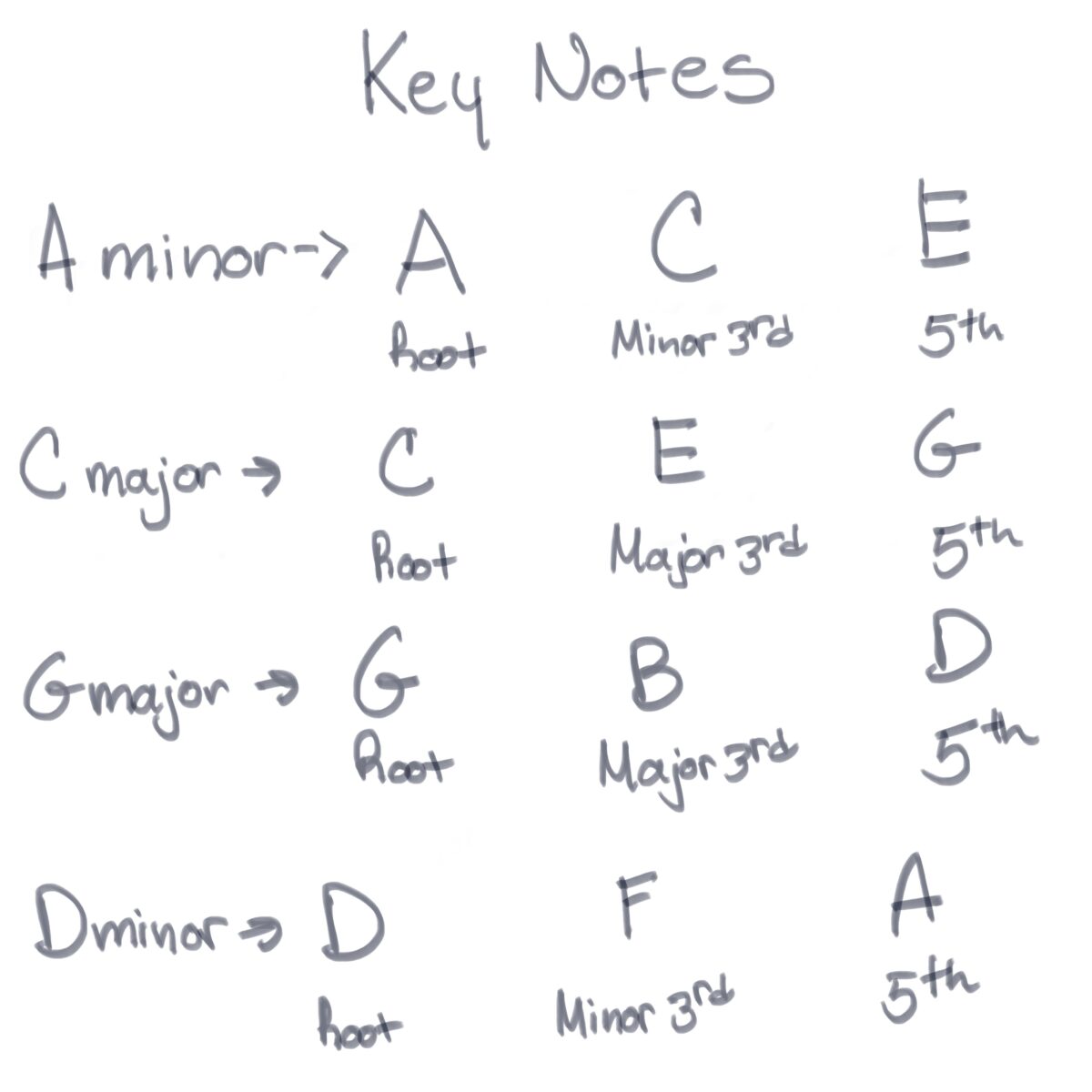

We begin with identifying and using chord tones as tools in our melody. What are chord tones? They are the notes that make up the tonal characteristics of any given chord. Every basic chord has a root, a 3rd, and a 5th, and each of these chord tones serves a different purpose in defining the chord, and in writing a melody.

Starting with the root, this note is the anchor of any chord, and is often at the beginning/bottom of the chord (with the exception of inversions and rootless chords where the bass will play the root). While it does not add color, it serves at the base on which the harmonic structure of each chord is built. It is the note that says “This is the chord, and the rest is decoration.” Check out this clip which details the anchoring impact that the root note has on a chord:

Color Tones

Major and minor thirds are arguably the most important notes in a triad (three note chord). Thirds define the basic color quality within any chord, regardless of the other notes included. A major third imposes a happy, cheerful tone, while a minor third imposes a darker, more melancholy feel. If you have ever heard someone mention the phrase “melodic playing,” they are referring to how you use the major or minor third in what you are playing. Check out the clip below to hear how a minor third impacts a chord:

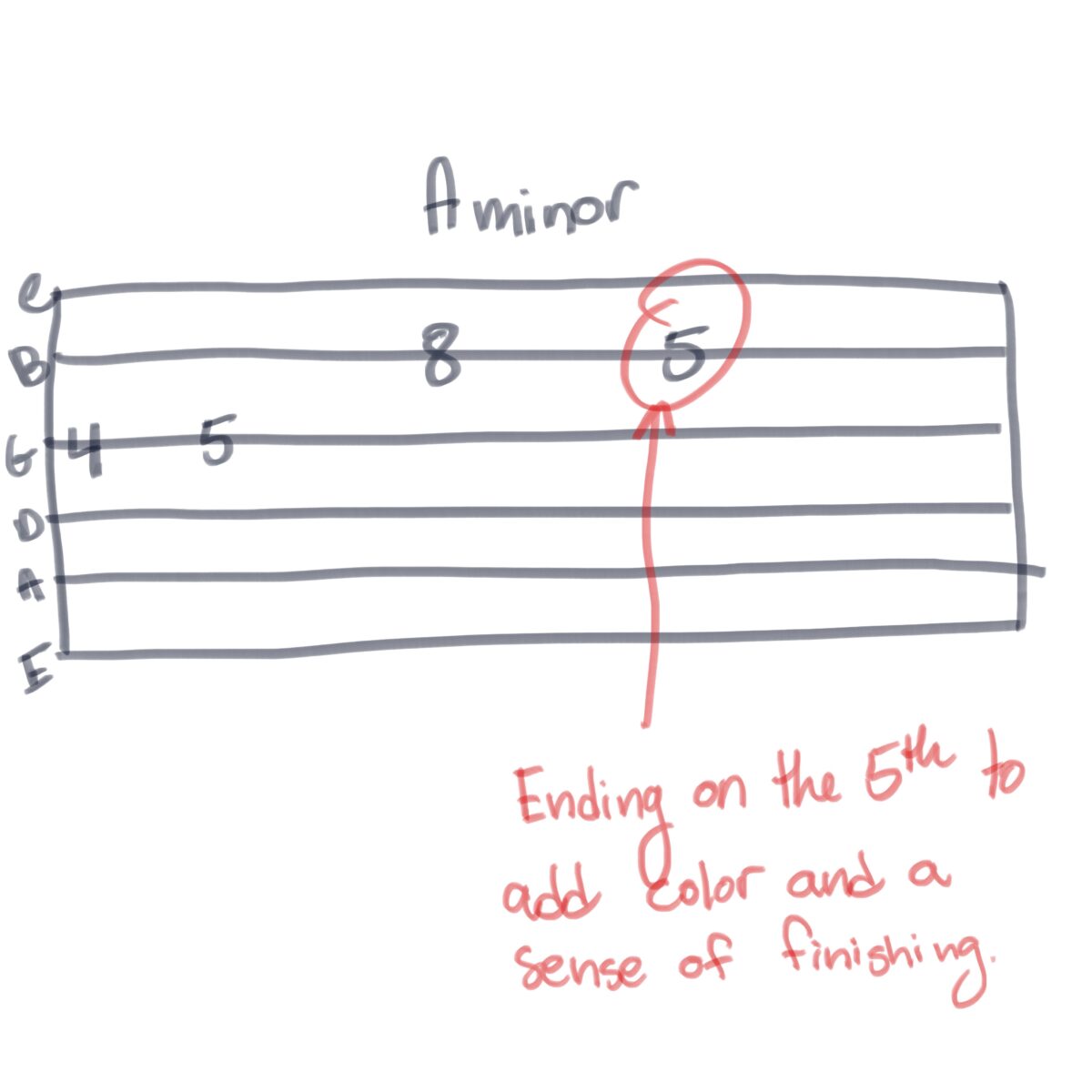

Last but certainly not least, we have our fifth. Now, the fifth does not have the anchoring affect that our root has, nor the heavy melodic implications that our thirds do, but the fifth is still valuable in its own way. I like to refer to it as a power note, most notably because the fifth is the note in a power chord that holds its signature sound. Additionally, the fifth still has SOME color, so when writing a melody, the fifth is a good option to go to when making creative “key note” decisions. Check out the fifth in our audio clip:

Chord/Scale Relationships

By definition, a scale is a collection of notes ordered by pitch. In music, scales and chords have relationships with each other, and knowing how these relationships work can help with not only writing melodies, but your overall playing ability. For the purpose of this post, we will be looking at how we can use scales to fill out a melody in conjunction with using our key notes.

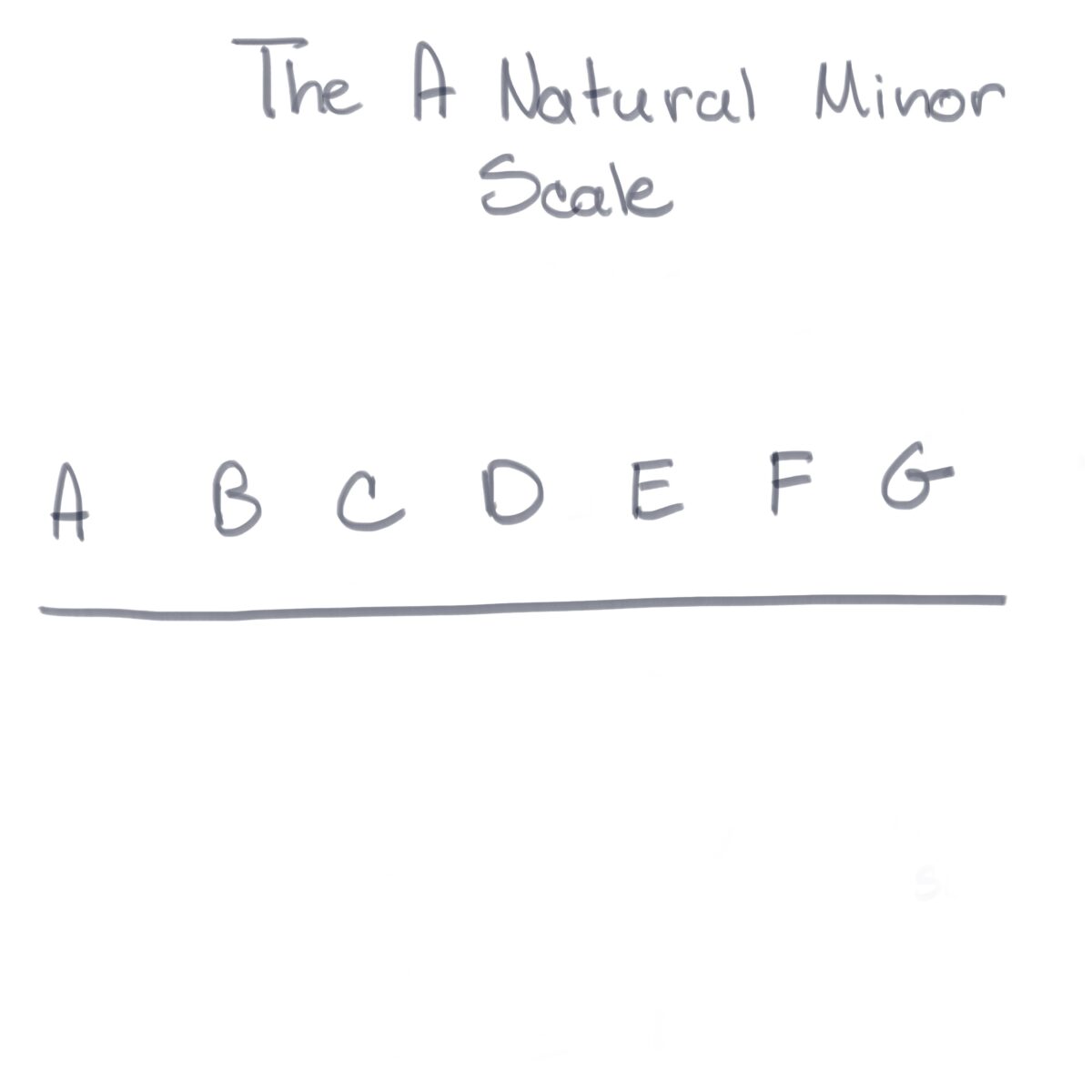

So, how do we know what scale to play/use? In a basic sense, minor chords yield minor scales, and major chords – major scales. Chord/scale relationships are much deeper and more expansive than that, but for the purpose of this post, this is as deep as we will need to go.

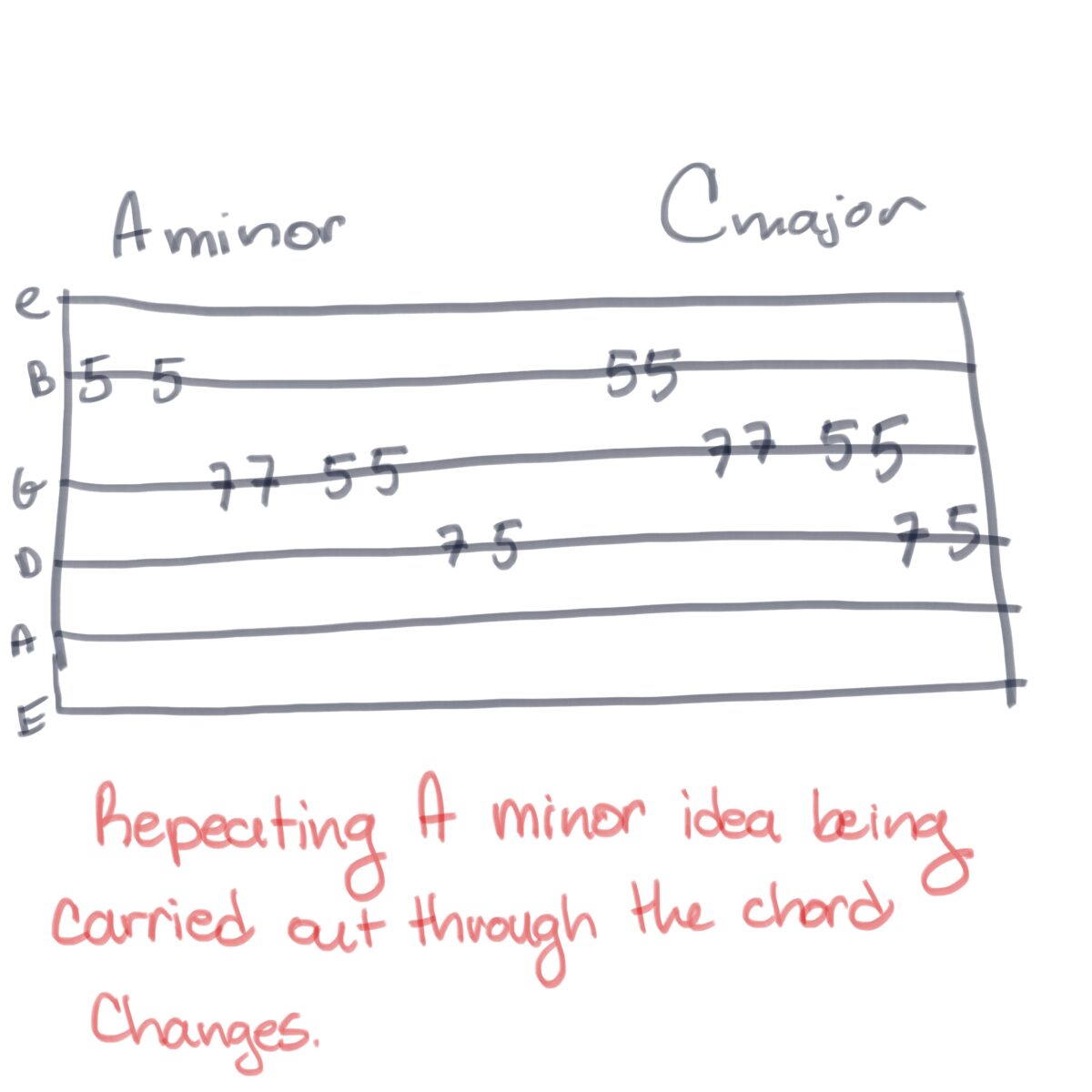

When looking at scales in the context of melody, deciding what scale to use can be decided by the key of the progression. In other words, you do not have to change the scale every time you reach a new chord in the progression. Let’s say you are in the key of A minor, and your progression is A minor, C major, G major, D minor. The A natural minor scale will work in this progression, and will sound correct over each chord. Let’s see what this looks like and how that sounds :

Time To Build Our Melody

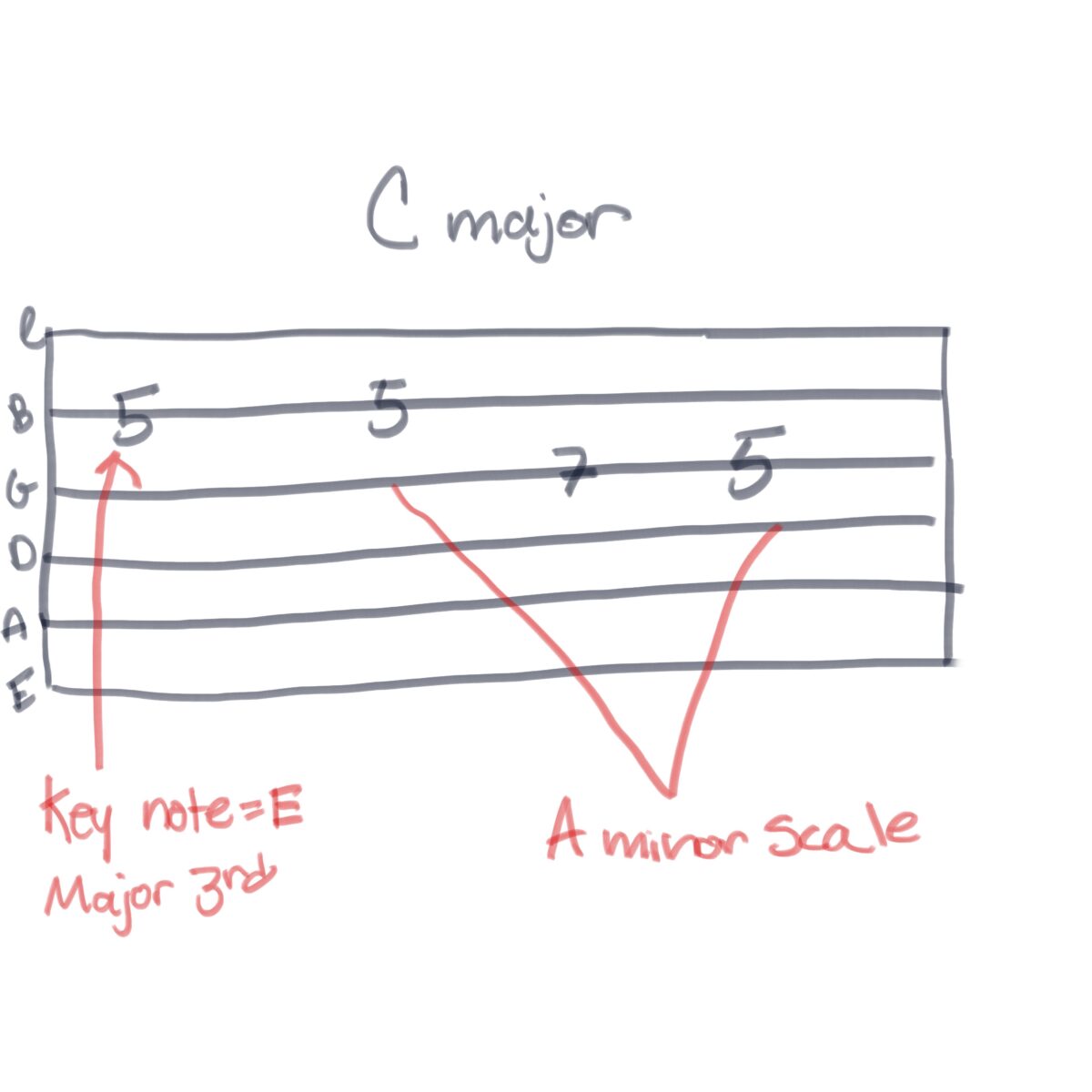

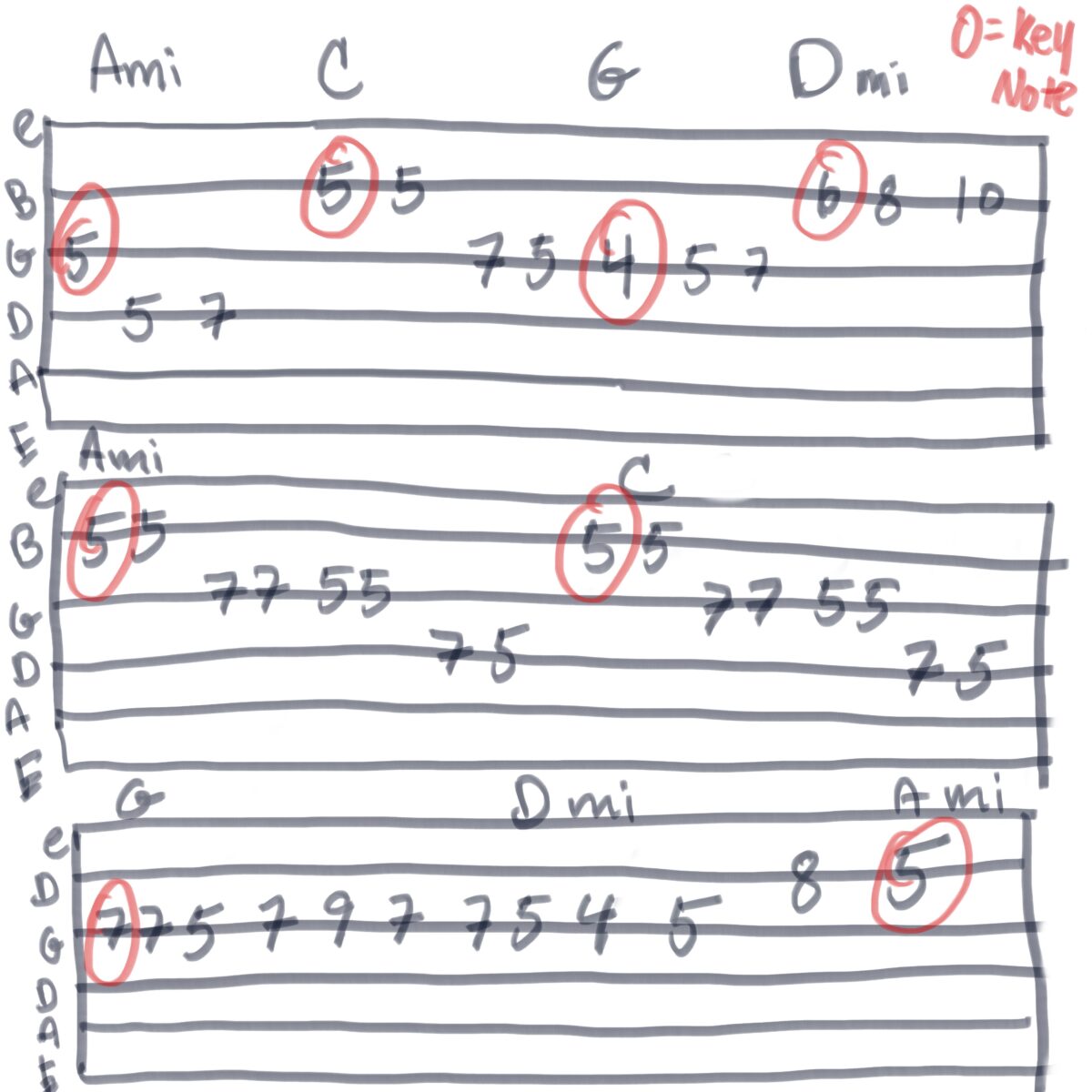

We are currently working with A minor, which means we will use our A natural minor scale, and start by looking at what note we can use to begin. To start, we are going to outline each chord with our key note of choice. We will use the respective third of each chord to outline our melody. Here is what that sounds like:

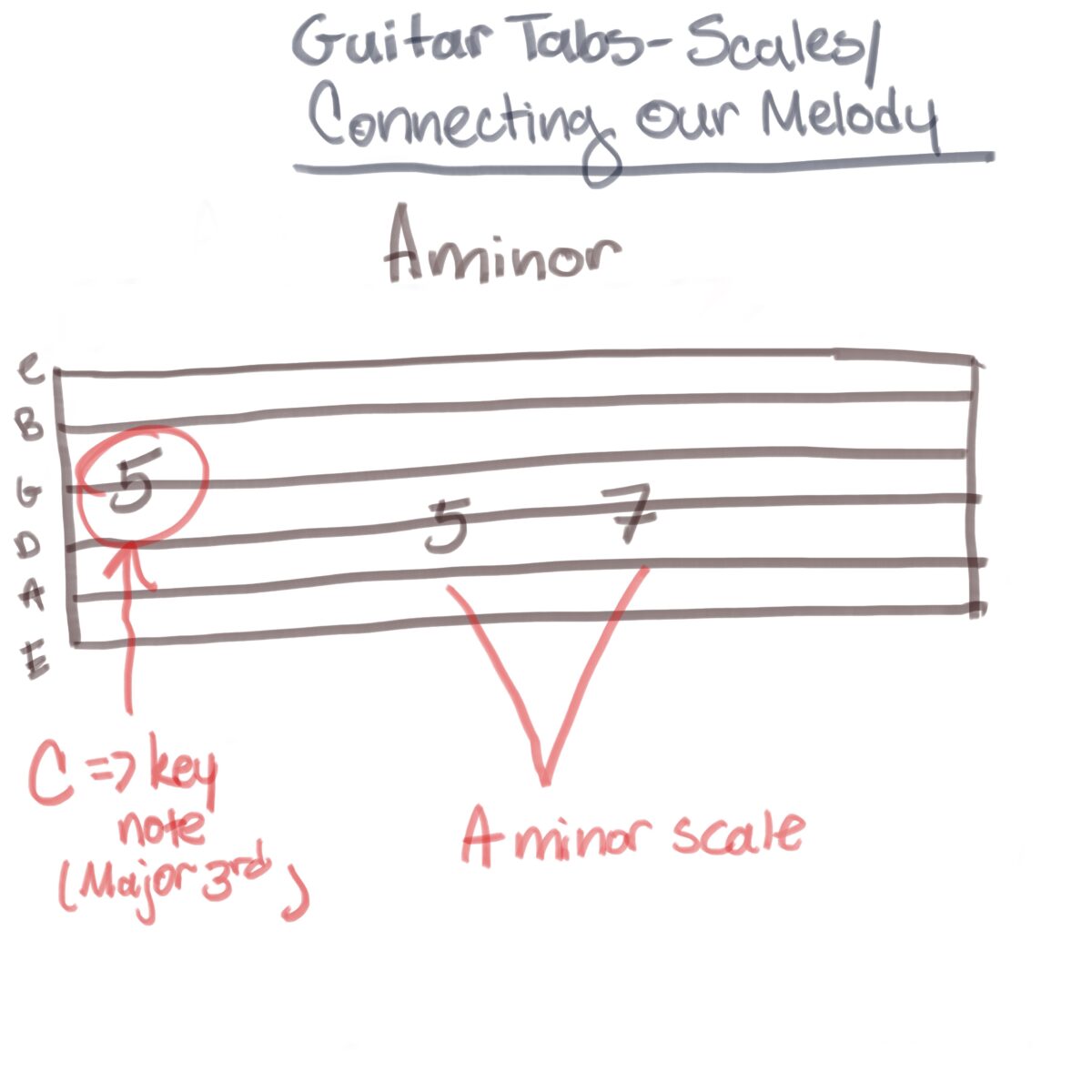

Now that we have outlined the melody with thirds, we will use the A natural minor scale to fill out the melody. The goal of using the scale is to connect the notes we have outlined. Our choices in how we use the scale should help connect our ideas and also complement them. The following melody will be visually outlined with guitar tabs.

With our A minor chord, we ascend first, but avoid playing the scale in a linear fashion to create an interesting motif.

Over C major, we are playing E (the major third) to add color. Since we first ascended the scale, we will now descend the scale to go to our next note. At this point, we have established an alternating pattern that keeps the movement of the melody interesting.

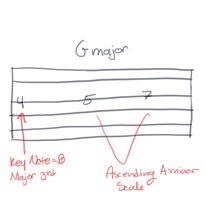

To transition from C major to G major, we will descend the scale to land on B as we reach G major.

We ascend again to F, the minor third of D minor, to finish this half of the melody.

How To Keep The Melody Moving

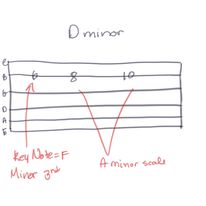

At this point, we have established ascending and descending motion. For the second half of the melody, we should explore other options for motifs. One very useful tool is repetition. This helps the listener mentally grab on to the direction of your melody as it evolves and provides a sense of familiarity.

Over A minor and C major, we will repeat the melody idea to show movement in the chord progression as opposed to the melody.

Over G major, we will repeat the line again with slight variation to spice up this idea a bit.

Now, with D minor, we will go from B to C to bring back the ascending motif we had at the beginning. This will set us up to finish the melody on the fifth of A minor.

Here is the entire melody with everything put together:

Now for contrast, I have included a version where the melody is sung rather than played for practical application:

What to Take Away From This Lesson

What I hope to demonstrate here is that melody writing with theory running autonomously in the background, can improve your instincts and decision making. Using key notes and chord/scale relationships are the key building blocks to making colorful choices and creating interesting motion. When you put all this together, endless possibilities are available. At the end of the day, you don’t have to be some sort of theory genius to do this successfully. But having good instincts that come from listening to and studying your favorite artists, and having a basic understanding of theory concepts can go a log way to writing something interesting!

Leave a Reply