Life’s questions never come to you clearly. Sometimes, such pondering comes to you in places where you have to face them. For me, it was staring at a wedding DJ, who I can best describe as your friendly, local church lady, firing up her Lenovo laptop and proceeding to do something which I can describe as one step above hitting play on some Pandora “Top 40” playlist.

Wedding staples were hit — think “Who Let The Dogs Out,” “Electric Slide,” and more — and bubblegum pop and hip-hop hits that have, thankfully, eluded my earspace beforehand, were played to an approving crowd. Lights moved and the dance floor jumped. This unlikeliest of DJs did what a DJ must do: rocked the party. But, yet, I wondered, “how?”

This is what led me to answer the esoteric question many are now asking themselves: Why pay for a DJ, when I can do that myself? Why, indeed. Well, here, I explain why and how the bread gets buttered. Here is where we get down to the nuts and bolts of what a DJ really does.

What’s A DJ?

Let’s get this out of the way. A DJ, or disc jockey (if you’re from some forgotten era), is exactly that: someone chosen to manage the music of a public event. This DJ has a catalog of music that they select from to create a mood, or to control the ambiance of a social gathering. There are DJs that create playlists to soundtrack cocktail hour, to set the atmosphere of “Treat Yourself Tuesdays” at the local spa, or to evoke some badly lit “’80s movie bad guy” hang-out location.

What they all share in common is that they’re in charge of keeping the music going, seamlessly (at best), segueing from one track to the other. Although they take can entertain specific song requests from the audience, most of the time (preferably), they’re left to dictate the order in which these tracks play.

Note: some DJs also play the role of MC, “shouting out” people in the crowd, notifying the audience of important goings on (“it’s ladies night,” somewhere), and interjecting pre-recorded songs with their own improvised music or singing/speaking.

The Things DJs Do

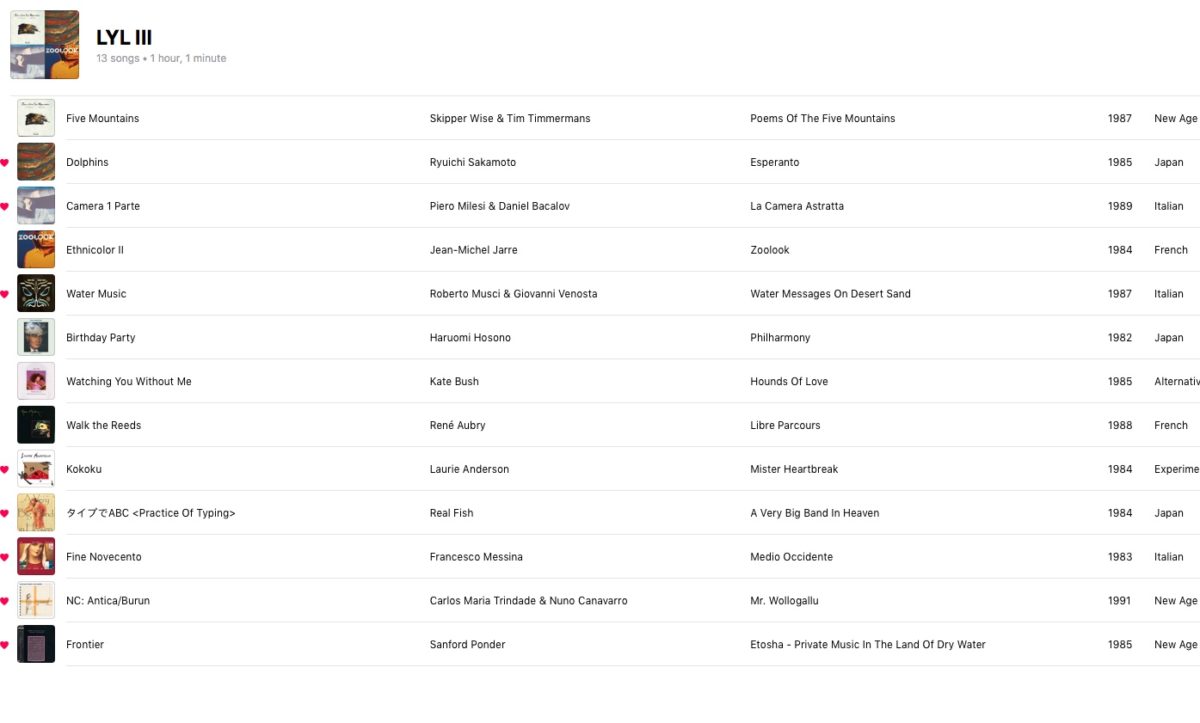

Programming

Every DJ, from the lowliest DJ working the basement of their friend’s place to the superstar entertainer fist-pumping the crowds in some Balearic island, is worth what they charge due to the way they program their playlist. If ever you’ve hit Command+N in iTunes, and created your first music playlist, congratulations — you’ve graduated into the world of DJ-ing.

The essence of DJ-ing begins and ends in the order and selection of music one plays for others. DJs have devices like turntables, CDJs, and controllers, that do one thing: play music. On a turntable, a DJ will cue, place a needle on the groove of, let’s say “track 3” from Album A, hit “PLAY,” and let it play out, as they physically load on another turntable “Track 7” from Album Y.

When they hear “Track 3” is just about to end, they cue up “Track 7”, and use a mixer to gradually (or abruptly, different strokes for different folks) bring the new track up in volume, while fading down the previous track. A DJ tries to play music that shares a similar sonic aesthetic, or tries to convincingly sustain a mood.

If you’ve ever made a mixtape for others, there’s not much rocket science behind it — you put at the beginning all the songs that would draw your audience in. From then on, it’s up to you to decide where this mix flows. Bad DJs are easy to spot, though:

- They have no rhyme or reason to their selections. Segueing from a Dirty South anthem to some obscure Disco Polo track isn’t genius. Likewise, playing songs that jump in tempo more than a pogo stick. Your ears never lie — listen to them.

- They give little care to what the audience would be open to listen to. This goes beyond taking requests. This goes to the heart of “reading” your room. Not everyone’s ready for some obscure minimal techno at your local blow dry salon.

- They have bad taste. Warmed-over hits get staler the more they’re overplayed. Awful tracks don’t magically become hot ones. Objectively, the DJ is the arbiter, and with great power comes great responsibility.

DJs Pandora or Put Your Spotify Playlist On Shuffle are often culprits of the above. Some claim they are taking listeners to a “journey” of sorts. For others, their role will be to maintain an audience engaged enough to stick around and buy more drinks, food, and participate in assorted bacchanalia. Then, there will be someone entrusted to make the greatest sacrifice: clear the space and make room for the event to end, letting the cleaning crew make their first appearance.

Good DJs read the room and play that room. Set aside all turntablist techniques and fancy effects: great DJs simply play and select great music.

Beatmatch

DJs differ from the common man in other ways. The common man plays one track, after another, without a care given to whether the tracks share the same tempo. DJs care a lot about the pulse of the music. To explain how this works, I’m going to ask you to revisit the opening scene to Wesley Snipes’ late-’90s vampire superhero tour de force, Blade.

Behind the wanton bloodbath is a soundtrack that seems to mutate at will, yet never seems to lose a (some would say) bludgeoning beat. You’ve heard it in countless techno hits. This “untz untz” is a steady rhythm that keeps such twisty music unified, even as all hell breaks lose (sonically, physically, spiritually?) in the background. So, what’s going on?

Beatmatching is what DJs do to make sure the tempo of one track stays steady with the tempo of another. To keep the “untzs” flowing, one must either slow down/speed up the next track to match the currently playing one. Both a blessing and a curse, this ability to keep a steady pulse allows DJs to dictate the overall energy of the room. Software (and huge SYNC buttons) exist that automatically do this for you.

Good DJs, who play music that’s not entirely driven by machines, and is not entirely monotonous, manually adjust play speeds and/or pitch controls to achieve beatmatching. Bad ones, well, they always seem to sound like they’re playing the same, darn, song…

This is why requesting tracks from your local, friendly DJ is a skill worth paying for. A DJ can seamlessly blend in the tempo of some requested track from whatever flavor-of-the-month EDM, overheard on a Forever 21 playlist, to their on-going throwback, UK Jungle music mix and not miss a beat, as they go grab a drink out of sheer embarrassment.

Phrasing

Think back to your favorite remixes. What makes them work so well? I wager it’s the way the components of it were made to fit. It just felt like they were meant to be together. Phrasing is this thing we don’t give DJs enough credit in doing. This technique of musically tying ideas from one track to another, is hugely important. Phrasing is what makes a mix seamless. You should reward them for doing this.

You don’t have to be a musician to hear relationships between songs. As humans, we’re wired to recognize repetitive patterns. Repetition allows us to discern sections in a song. We can say: this is the chorus, these are the verses, this part is wack, this part is hot, this part sounds like I’ve heard it elsewhere, etc. Taking apart things and songs is in our lifeblood. When we appreciate the feel of a certain track, of course, we’d love for the next track to seamlessly keep it going. We can recognize when certain bits of a track could lend themselves to another.

DJs recognize this and (technically) “rearrange” these pieces, taking apart pieces from various songs. What they’re hearing is a blend of one section with another.

You might not need to listen to a whole track, if repeating a just few bars here and letting another bar from a different track keeps that vibe going, sustaining the larger, general, musical idea. As long as it sounds musical, you’re creating something refreshing for the audience to hear. Making sure the end of one track doesn’t really signal “the end” is phrase matching.

EQ-ing

Here’s a joke: What’s the difference between EQ-ing and putting your hands in your pockets? Beats me. Ask the DJ. EQ-ing is such a deathly important thing that a DJ does — but it’s hard to quantify unless you hear it and do it.

The act itself is simple: you get three knobs (High, Mid, Bass) and you turn them to either filter down or accentuate certain audio frequencies within their spectrum. The majority of the knob-twiddling you see a DJ do is exactly in a precious bit of mixer real estate: the EQ, or equalizer, section.

You wish a bass line in a certain song wasn’t buried in the background? Voila, turn up the bass knob and hear it more pronounced in your mix. You love this vocal line but it seems to die off with each repetition? Turn an HPF (high-pass filter), sweep the Mid, and watch those vocals build to a crescendo. Much like the equalizer in your stereo system, a DJ’s EQ controls exist to “sweeten” music that might ordinarily sound a bit flat. But there’s much to EQ-ing than this.

EQ-ing is an art form. With equalizers, you can bring various tracks together with overlapping musical bits, and pick and choose the best bits to mix. For example, let’s say you have two dub songs ready to cue. In theory, you could just fade between them and hope for the best. In real life, you shouldn’t. What happens when two bass lines meet? They turn to mud. This is when EQ-ing does something else. EQ-ing lets you add by subtracting, too.

DJs play with their mix by filtering out specific segments of songs, to allow segments from other songs to fit into that carved-out sonic space. It’s basic science: one can only add by subtracting from filled space. Now you can fit the better bass line from one track over another. Now you can make room in the higher frequency range for that lovely vocal to come in, without detracting from an ongoing melody line. EQ-ing also creates the bane (or lifeblood) of many a club-goer’s existence: the drop.

The drop is a technique where a repetitive musical phrase is continuously being accentuated via equalizers, only to suddenly filter down sonically into a wobbly puddle of subsonic bass music. This drop builds tension, making you want to hear something that will sweep up everything in the sonic spectrum. That’s the drop.

DJ mixers have audio filters, typically LPF (low pass filters) or HPF (high pass filters) that ignore a certain section of the sonic spectrum, letting through only what lies below or above of it, respectively. Sweeping these controls back and forth moves everything sonically higher or lower, en masse. Drops and builds (its bizarro offspring) are made this way.

Key Matching

A DJ wouldn’t be a DJ if they couldn’t mix in key. Most DJs in the wedding circuit don’t have to worry about this, but for performing DJs, whose mixes are the performance, mixing in key is an important technique to master.

You mix in key (or key match) by adjusting the pitch or speed control of the deck that needs to match the key of another playing track (or tracks). In the old days, when disc jockeys were a thing, they would listen to a track playing in one deck and prepare the next track to approximately stay in the same root key of the original.

Matching keys would allow you to create a whole new song out of two (seemingly) different songs and different parts from said songs. You don’t have to key match everything — that gets redundant and brutal to hear after a while — but in choice moments, keymatching is another difference between a DJ and a layperson.

In our modern world, DJ software like Serato and rekordbox automatically scans your library and gives you a visual readout of the key your track is playing in. Likewise, modern technology usually provides you with a virtual or physical knob you can easily tweak to bend sonic time and get that track in key. Now, armed with that info, you’re able to do a couple of things.

One is to easily find tracks that share a key and program them together. Another is to let the software automatically place one of the tracks as a “slave” to the master key of another. Finally, there’s the ability to put your piano lessons into place and use this key info to sequence tracks that make sense “harmonically” with each other, dusting off your circle of fifths for a greater use.

Images by author

Leave a Reply