Moog would be hard-pressed to find a better ambassador to what the essence of Moogfest stands for than Suzanne Ciani herself. A pioneer in every way, Suzanne nurtured her love of the Buchla synthesizer and music itself into realms that scarcely existed when she began her career. Using sound design as a platform for creativity, she parlayed all her knowledge and discovery into creating one of the first commercial production studios: New York-based Ciani-Musica, Inc.

The sound of a GE dishwasher, the sound of a bull in a china shop, a Black & Decker Cutter, all this and more were part and parcel of the film and TV scoring work she was able to produce from her Buchla. Ciani’s work could be so off-beat, but intrinsically on-point. Do you need an example? Take that little bit of “rocket flight” in the Starland Vocal Band’s “Afternoon Delight”. With mere seconds of sound Suzanne demonstrates the fascinating attention to detail and artistry that only she could add to a piece.

In our interview, Suzanne stresses how for her there was no line separating her artistic work from her commercial commissions. Now that we have the benefit of time to fully absorb her trajectory, we can appreciate how right she is. All of it was intensely private and personal. When Ciani began studying for a masters in Music Composition at The University of California at Berkeley, it was her fascination with the Buchla that led her away from her piano studies. When she began her journey, the electronic music world was far different than ours.

Imagine having to punch a card to program a synth. Then, imagine coming back a day later to hear the result. That’s the world Suzanne Ciani lived in. The promise of the Buchla, or at least the one she initially heard, was the freedom to express yourself instantly. Ciani’s desire to fully understand the synthesizer would lead to her dedicating her life to the instrument. There were no manuals for this, but in time, she would add her own chapters to the development of the synthesizer, alongside figures like Don Buchla himself and other groundbreaking teachers like John Chowning and Max Mathews.

During the mid-1970s, when Ciani performed live Buchla concerts, audience members were left dumbfounded trying to understand how someone could create such music with no keyboard attached. For Ciani, the turning point might have been realizing that the keyboard was no longer necessary, that this synthesizer was its own unique thing. Her commercial work came from ad agencies discovering the unique, inexplicable “it” that she could add using these tools. That she could make money doing something like this was a welcomed surprise. However, her love of music never diminished.

When Seven Waves came out, it married everything that led up to it. It was Ciani’s love of romantic, sensual melodies matched with pure electronic explorations. It was unclassifiable then. This is something Ciani struggled with. How could you label music like hers — music that’s grounded in electronics but with roots planted in deeply human feelings? This paradox troubled record labels, and one by one, each rejected her ideas and concepts. Ciani struggled mightily to get anyone in America to release this kind of music. When her search took her to Japan, she would meet a respectful audience that took the time to actually listen to and release her music. When 1986’s Velocity of Love was released to American audiences, it sparked a radio revolution, with the single of the same name becoming a #1 song on New Wave stations. By her third album, Neverland, the New Age genre had solidified, and Ciani received her first Grammy nomination in this new category, finally clearing a place for her music in record stores. However, Suzanne Ciani was never about labels.

This is something you feel when Ciani appears in vintage videos explaining to others how a synthesizer works or how sounds get created. Heck, you even see this in recent interviews, much like ours. Rather than recite technical jargon few could digest, she shifts the focus into recognizable concepts we can all process. Ciani’s belief in the potential of electronic music and electronic instruments has never wavered. They may be machines but we have the ability to bring them to life. When Ciani started to compose music solely for acoustic instruments, this brief hiatus didn’t detract her from coming back to the Buchla that started it all before.

Although the Buchla she’s using now might not be the same as before, her recent performances solo or with Neotantrik display how timeless her creativity remains. This is something you’ll hear in recent releases from Finder Keepers Records or that you’ll see in her recent collaborations with Moog, perhaps you’ll experience it live at Moogfest and elsewhere in the near future. You see, Ciani goes way back…

Interview With Suzanne Ciani

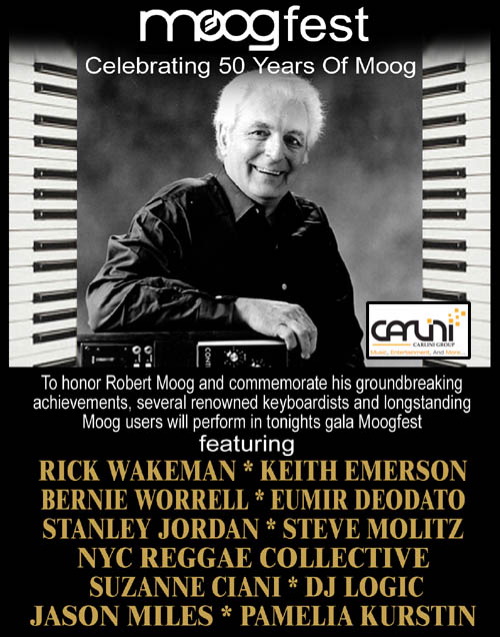

zZounds: Let’s start with the beginning. You were there in NYC at the first Moogfest. Back then you played on a Moog Piano Bar.

Suzanne Ciani: The interesting thing was that the Piano Bar was designed by Don Buchla. What happened was that Buchla designed it and they collaborated on the manufacture. And instead of calling it the Buchla Piano bar they called it the Moog Piano bar.

zZounds: Was there any reasoning behind this change?

Suzanne Ciani: All these things you have to know the story behind, or else you won’t know what’s going on. It’s [an] interesting history, because Buchla and Moog were the salt and pepper of the industry. It was polarizing because one was East Coast and the other was West Coast.

I always loved Bob Moog as a person, and over years that animosity between them wore down and there was no polarization.

The Piano Bar symbolically represented the merging of these two companies. By this time, these two seniors of design were friends; they worked together. You know, it has always been tricky to get manufacturing done. I played Moogfest because I wanted to play the Buchla Piano Bar. I wanted to represent Buchla. I saw that Moogfest was somehow becoming, or being billed as, a big umbrella fest for all kinds of electronics. And I wanted to make sure that Buchla was represented there. Moog had always had more of the rock and rollers and it was sure fun hanging out with Keith Emerson and all these guys backstage.

zZounds: Looking back at the Moog Piano Bar, it seemed that until then Buchla had a way of trying to get away from the whole keyboard thing….and now you had this out there.

Suzanne Ciani: Buchla realized that the keyboard was not an appropriate interface for an electronic system. It just didn’t make sense to have a mechanical action to interact with an electric system. I don’t know why or who asked him to invent the Piano Bar but it was a wonderful thing. I’ve used it many times when I travel to write. You know, I went to Venice and I could bring my Piano Bar, set it up on a grand piano, and use it as a compositional tool…it would create and transmit MIDI note data to my MOTU Digital Performance software.

zZounds: Back then, in 2004, it appears you were touring your Classical/New Age material which was more piano driven and symphonic.

Suzanne Ciani: My music evolved in an interesting way. My childhood instrument was the piano. When I first made commercial music it was electronic because I fell in love with the Buchla and threw the piano out the door. But then over the years, I slowly migrated back to acoustic instruments and the piano. My second album was pure electronics except for the last piece. Suddenly a piano came in and the evolution from then on was such that I went all the way in, adding acoustic instruments until, yes, there was an orchestral album. And now I’ve gone back to electronics again, which is kind of strange.

zZounds: And that’s what’s interesting to me. At this year’s Moogfest you’re doing your new electronic performances. Is there a certain excitement in this?

Suzanne Ciani: I’m doing these performances in honor of Don Buchla and Moogfest is creating a special venue/moment in honor of Don Buchla. That’s why I’m there, to honor Don. I no longer see a polarized view of electronics. I’ve started to work a little bit with Moog…they’ve asked me to work with them. Now, I asked Don…is this cool for me to work with them?

And he says yeah. When you get older, and you let go of a lot of that stuff, it all relaxes a little bit. I have Don’s blessing to perform at Moogfest. Though, I’m sorry he’s not going to be able to come because he’s not doing well.

zZounds: I was looking at Moog videos and you were on the System 55 which is this large, classic, modular synthesizer. It’s interesting because people know you as a Buchla user, and you have all this history behind using Buchla.

Suzanne Ciani: But, you know, when I started out I did play Moog at the Mills College Music Center. They had a Moog and the director of the center gave me the Moog for one summer. So, I did have an experience with the big Moog. When they asked me to play with the 55, it was because I was someone historic from that period. Even though I hadn’t played that Moog in 40 years, it was like riding a bicycle. If you do something when you’re very young it all comes back to you.

zZounds: Sometimes I feel like synthesizers have their own vocabulary. Is that something that you encounter when you handle all these kinds of synth?

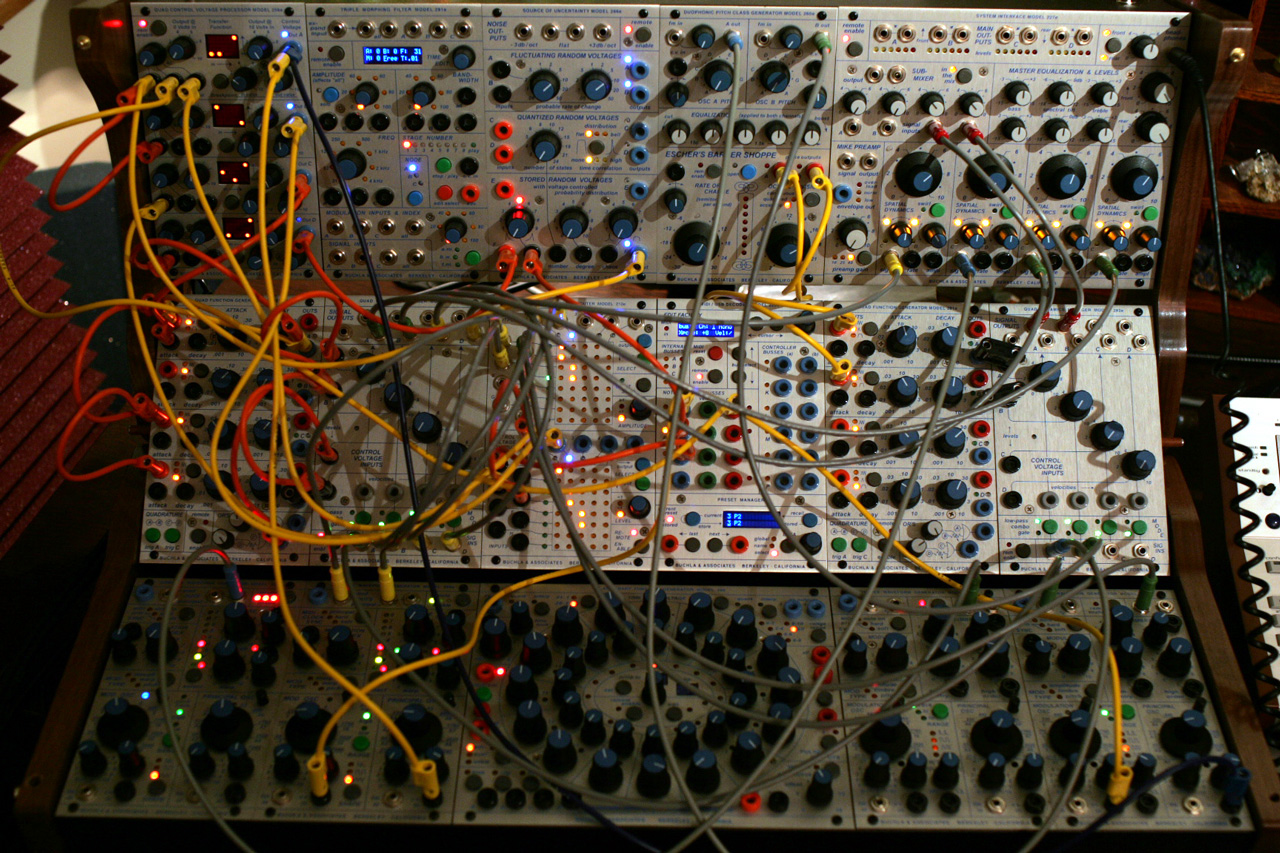

Suzanne Ciani: The Moog is very sonic-centered. It has a beautiful sound and wonderful filters, and a certain quality to its sound. The Buchla was never about the sound. It was about way the sound could move. It had a lot of voltage control. It had a lot of different ways of controlling the movement of sound. The Moog did not have a lot of different ways of controlling the movements of the sound. It was fine as a keyboard instrument. So, it was a slightly different world. I see that very clearly now.

Back then I used be frustrated: why can’t this one do that and why can’t that one do this?

The Buchla was never about the sound. It was about way the sound could move.

zZounds: At Moogfest are you going to be performing solely on Buchla?

Suzanne Ciani: Yes. I’m bringing my Buchla. They’ve also asked me to do an installation which is going to be using their instruments: the Mother-32. I was explaining to Emmy Parker [Moogfest Creative Director] how, in the early days, I would do pieces that lasted for weeks…how to set up a piece that plays itself…one that goes on and on. And that’s what this installation is. It’s going to be evolving in real time, playing itself. So, in order to do that, truly you do need a lot of control. A lot of voltage controls specifically. We’ll see how this works.

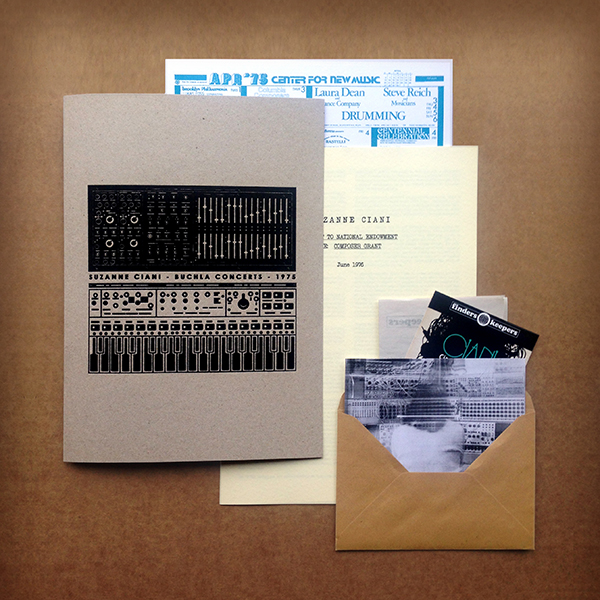

zZounds: I know recently Finders Keepers Records released a LP of two of your live Buchla performances from 1975. What was that like?

Suzanne Ciani: In 1975, I did a live performance in NYC that was recorded. It was at a radio station (WBAI). Then I did another recorded at Phill Niblock’s loft. They were live electronics, because in those days, it was my feeling, that Don Buchla was promoting the concept of the Buchla as a live performance instrument, it wasn’t a studio instrument. In order to play it properly, you played it live. I had dedicated myself to performing it on the Buchla which was very challenging, and now, I’m doing it again, and it is even more challenging because the Buchla has changed.

I played the 200 in the ’60s and ’70s. Now I’m playing the 200e and it’s a completely different animal.

zZounds: Is it different in control? I’d imagine the facade and the construction might be the same. What’s so different about it?

Suzanne Ciani: You know, it’s a complex thing what happened with the technology. Because basically, it’s a collaboration and conversation between the artist and the designer. Sometimes, it’s a more open conversation and sometimes less. I don’t know what happened, but a lot of things were lost in the new machine, even though it gained a memory. The early machines had no memory and performing on them was a feat of magic. Everything you had to create on the spot and there was no going back.

Now there are memory locations and you can store something.

zZounds: I read somewhere that you had your original Buchla, which you had for a long while, and somehow it got stolen.

Suzanne Ciani: Yeah half of it was stolen…

zZounds: Is it like finding your way around a relationship? Finding how that other side of the relationship works with you. Is that something you’re discovering as you perform or are practicing at home?

Suzanne Ciani: In the new Finders Keepers release, there’s one collector’s edition that has something interesting. Andy Votel, who runs the label, is an amazingly thorough person. He published this paper I had written on how to play the Buchla. It was a paper I had written for the National Endowment for the Arts because they gave me a grant. You can open this thing and see this whole recipe book of how you play the Buchla. I think there are still valid recipes in there for people to consider. What is this live electronic music? How do you keep that sound moving? What are the controls you have?

Don Buchla was always dedicated to live performance. He had a lot of interfaces, the Marimba Lumina, the Thunder and Lighting. His main concept was performance, and that got lost in the world of electronic music. He thought of this as a new type of instrument, with a new set of techniques.

So, what I’ll be doing, in a way, is doing what I was doing in 1975. But I can’t do it as well as I did it in 1975, because I don’t have certain modules that I had then. Those have disappeared…such as the Multiple Arbitrary Function Generator.

zZounds: Since you don’t have all the modules you had, is that introducing a welcomed randomness you weren’t expecting?

Suzanne Ciani: It’s not welcomed. I mean, it’s sad that you don’t have the ability to control sound to the same degree you were able to 40 years ago. I think a lot was lost, but there are other things found. Technology is ever-changing, you can’t just sit in one place.

You want to get to know the machine. You can’t impose your will on it.

But for me, because my music is tonal, I like pitches. Some of the new modules are not as calibrated for pitch music. And that’s a problem. When you can’t have pitches when you want them, it can be a challenge. But then you discover other things. It’s a joy, it’s an interaction. You want to get to know the machine. You can’t impose your will on it.

zZounds: In the past when you had to do commercial work, were you thinking more textural or tonal?

Suzanne Ciani: My early commercial work was what became sound design. I just stumbled into this natural poetry of interpreting. Because I was in electronic music and it was a natural thing to be able to interpret feelings, sounds, ideas and concepts. Because it was just like having a big paintbrush that you can paint all these different colors with. The sound of heat, the sound of cold, the sound of energy, the sound of a bull in a china shop, a talking dishwasher.

But because I was classically trained, I was able incorporate that sound design into a more traditional approach. I always loved melody. Melody and pitch were part of my music.

I was curious about something you said. Something about Seven Waves and The Velocity of Love, do they have detractors?

zZounds: Personally, I see that certain people have a misguided idea of that music shouldn’t be open-heartedly soft or romantic when it’s synthesizer-driven. These are the ones that associate synthesizers with either being cheesy or being Emerson, Lake, and Palmer-esque, very in your face and/or obtrusive. It seems like detractors put down this kind of music for not using the full scope of what a synth can do. What are your thoughts on this?

Suzanne Ciani: For me, the most important aspect of the synthesizer was the machine-dependability of the rhythm. With it, I was able to create real slow music. For human beings to play very slowly in a regular rhythm is difficult. I think it’s a subliminal experience when you know that beat is coming on time, you can depend on it. That’s the whole essence, underpinning the peacefulness, the sensuality and the beauty of the music. And that is a very machine-like capability, just that rhythm. You don’t have to propel it with drums and it’s just the machine itself.

And that’s what I did in Seven Waves. I said: you know this can be the slowest music. It can be half the speed that people are used to. I don’t know what using the whole synthesizer means. A synth can make noise. But I’m a composer and those albums were a synthesis of my pure electronics with my classical roots. And they were written out and orchestrated. They were very different than what you’d hear at live Buchla performances. The live Buchla was pure electronics. At the time, no one understood it. I could do a live Buchla performance and people wouldn’t know where the sound was coming from, they just didn’t get it. It was always in quadraphonic in those days, the movement of the sound was important. And I trust we’ll have a good sound at Moogfest.

You see, Buchla was always interested in the spatial location of sounds. But Moog is not that interested in that. But I think it is a very important part of electronic music this spatial interaction.

zZounds: Do you think you made this album in response to music going in the wrong direction? Or was it some personal choice of yours?

Suzanne Ciani: These albums were extremely personal. Seven Waves took two years to produce. It was a work of love. I couldn’t get a record deal and I realized I would have to do it myself.

zZounds: You actually had to go to Japan to get your first album released.

Suzanne Ciani: The Velocity of Love I did in the U.S. The first record deal I ever got was in Japan. I went to Japan with Six Waves. I called my compositions waves. They said it was bad luck, you had to have seven.

zZounds: Was the “Seventh Wave” the final song you created for the album?

Suzanne Ciani: Yes. And then they gave the names, because I didn’t have names for the waves. I just had Wave One, Wave Two, etc. The second album I continued, I had waves eight through twelve. But then when that came out it was called The Velocity of Love.

zZounds: Can we revisit the question you had about detractors? The detractors weren’t listeners but record labels. What was the main issue you were running into with them?

Suzanne Ciani: The main issue in those days was that record labels wanted to give you a few hours in the studio to do something. For me it took months in the studio. They thought: “we’ll give you a drummer and a bass player.” So, for instrumental music, and especially instrumental music of this new type of instrument, there was no operating system for that. And you really had to do it yourself. I know there were some exceptions and that’s why I went to Japan. Tomita was a Japanese composer who had some support from his record label.

Basically, what you needed was a long time in the studio. This was before the time of home studios. When I did Seven Waves I actually rented multi-track, 24- or 32-track tape machines and it was analog. Of course now we know how wonderful analog is but when the Velocity of Love came out it was during the very timing of the CD. So, every record label wanted to have on their boxes DDD. Digitally recorded, digitally mastered, and digitally mixed. Because my Velocity of Love wasn’t recorded digitally it didn’t qualify for, you know, that craze of the moment.

The whole “digital” thing was used as a marketing tool.

zZounds: You probably heard New Wave music and Art Rock that used synthesizers. Was that the notion that you were seeing, that maybe what you were doing wasn’t just trying to use the synthesizer as a gimmick but composing with the actual synthesizer in mind?

Suzanne Ciani: You know, the genesis of this music for me was very personal. It wasn’t coming from outside. There were record labels that said we’d like you to do Switched On something or the story of the end of the world. Could you paint this electronic concept album? But, for me I wasn’t doing that. It didn’t make any sense to approach it from the outside.

My music, it was very personal. It was something that came from my root system of classical music and electronic music. My frustration was at people not understanding my pure electronic music. By combining the two with my desire to create the music I needed and I wanted. Which to me were some of the essences of electronic music: dependability and sensuality. It’s too hard to talk about actually, because there’s such a wide gamut of what electronics can do.

My music, it was very personal. It was something that came from my root system of classical music and electronic music.

zZounds: Back in those days there seemed to be a lot of compartmentalization of your releases. And now with the passage of time, it seems like people can rediscover this music without the baggage you had to fight through.

Suzanne Ciani: Actually, the term “New Age” didn’t come into being until my third album Neverland, which is the first album I did for Peter Baumann’s [ex-Tangerine Dream] label, Private Music. That was when New Age came to being. So, my first two albums didn’t have any category. And that was really a problem in a way because you wouldn’t know where they were in the record store. If, you wanted to find it the record store where did you put it? It needed a category. The category itself was a marketing tool. So, if you had a category “New Age,” as horrible as that was, at least it meant that people knew where to find it.

And what does this all mean? You know, we’re all caught up with with these concepts. And it’s not a concept. It’s an experience.

zZounds: Does that experience tie into that whole idea of New Age? A lot of people were making music for relaxation or to express something like the ocean. Were you trying to make music that thought of sound in that way?

Suzanne Ciani: No, I was never trying to do that. It’s very complicated because if you had the concept of wanting to make pretty waves and relaxing people you could do so. But that’s what not the Waves were about. The Waves were a compositional form. The compositional form was that the song would build to a climax and release, just like a wave did. So the energy of a wave which built and released, the rhythm of the wave, the slowness of the wave. For me, the reason I called my pieces Waves was for many reasons, but not because I was trying to lull people.

I think there’s always the distinction that you can approach something organically, where you generate it from your own inner genesis/spark, or where you’re designing something from the outside. And that’s a difference. When you’re a designer you’re implementing something, when you’re an artist you’re not implementing anything.

zZounds: That seems to me to be the separation line between your commercial work…

Suzanne Ciani: No, I worked as an artist in commercial work. I was never less than an artist when I did my commercial music. I had complete control. Nobody told me what to do and they got the best results that way. One of the reasons, no one told me what to do was because they were afraid. They didn’t know what all that stuff was.

But, you’re a writer, you know, if you want to do a creative thing you want to have the energy to do it.

zZounds: I agree. Sometimes you get things that are assigned to you and you try to find creative ways to do things that could be very rote.

Suzanne Ciani: You have to make something your own.

zZounds: This segues into something else. Recently, there’s been a rediscovery of early female electronic music pioneers like Laurie Spiegel, Pauline Oliveros, Eliane Radigue, and it seems that in a lot of their own interviews they bring up how much they struggled to get their music released.

Record labels and other musicians thought that you had to make music a certain way, more akin to modern classical music (very atonal and structured). They wanted to make music that was more textural and more melodic. And I know that you’re working with Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith on some tracks. This struck me because she’s a younger musician who is seeking guidance from someone like yourself who might have faced the same issues.

Suzanne Ciani: Yes, we’ve worked together. There’s a series from a record label where they pair an older artist with a younger artist performing together.

zZounds: Has that music been released?

Suzanne Ciani: It’s about to come out. I just got the test pressing, but I haven’t listened to it yet.

zZounds: What did you take from that experience?

Suzanne Ciani: You know this whole process for me has been one of surprise. An ongoing surprise.

zZounds: When you’re working with her it seems you almost have the same tools. Were you sharing the same experience navigating around these instruments?

Suzanne Ciani: Except, I have the Lamborghini. They’re actually quite different. The Buchlas that we play. She has a Music Easel. I was never a Music Easel person. I’ve always been into modular. Since the beginning.

It’s challenging now, in many, many ways, for young musicians to get a hold of the big modular systems.

zZounds: Yeah, most are very expensive.

Suzanne Ciani: They always have been. And it means it’s a commitment to take them on because they’re so expensive. Kaitlyn, she’s young. I met her in Bolinas (CA) which is where I live. She no longer lives here.

So, what is it like to come back after 40 years and to see this new evolution of interest in electronic music? It’s kind of a miracle it’s coming back. Because electronic music digressed. It kind of died the first time around. Because it didn’t find its legitimate path system.

But now, with the euro rack system, kids are starting to get back to basics…it’s a non-keyboard world and they’re trying to find new controllers like the ones from Make Noise.

These things, they’re tools and I still haven’t found the level of stuff that was back in the ’60s. I think it’s going to come around again. I do think we’re going to make progress this time around.

zZounds: Do you think it’s important that music, at the end of the day, is the final result? Regardless of whether someone got to it via a modular synth or software. Not worrying so much about the process but the result.

Suzanne Ciani: There are two things going on. Because there is the actual result; you recorded something. And there is that other thing, which is the performance of the thing. That’s what I’m excited about. People are starting to look at these things as performance instruments again. That didn’t get fulfilled the first time. Who knows if it’s going to be fulfilled this time?

I know I’m probably the only one on earth who doesn’t play through Ableton Live. I don’t even know what it is. When I was growing up on electronic music…This is going to sound like an old story… There were no schools, there wasn’t any methodology, there were no programs, no tech guides, so everything was a bit random and it was always new. That was what we loved about the world then, because it was completely unknown. Now kids go to school and they don’t have this kind of discovery.

When I was growing up on electronic music…There were no schools, there wasn’t any methodology, there were no programs, no tech guides, so everything was a bit random and it was always new.

zZounds: Do you think there’s too much information? There are thousands of software plug-ins out there and iPad apps vying for their attention.

Suzanne Ciani: I think it’s all fine.

zZounds: I use Ableton Live myself, but I know how easy it is to get lost in presets and not want to go that deep into sound sculpting or synthesis. If, boom a preset is there, I can just use that as a starting point.

Suzanne Ciani: I guess it’s whatever you love to do. For me, the performance of the Buchla was hands-on: you know, you turn knobs, you move dials, you flip switches. In the Finders Keepers release you can hear the switches being flipped. These were not recordings made direct to tape. There were microphones in the room. So you hear all the noise of the performance. And that experience of being in the moment, moving wires and flipping switches, changing things and creating results, then following up on that, in that moment, then moving from one moment to the next — that’s what it’s about.

This is a living being, that instrument. That live electronic thing. It has life in it. And when you’re interacting with it, you’re in life with it. And you’re moving it and it’s moving you back. It’s a living organism system. That’s the beauty of the thing as a performance instrument.

If you pick up any instrument, like a violin, and you don’t know how to play it, you won’t get any sound out. Then there’s the other thing that is the composition. The thing about performing live is that you are the composer and the performer. So you’re doing both. It’s a kind of jazz.

zZounds: I know you recently performed with Neotantrik. Andy Votel is part of this group. Do they use MIDI keyboards or any kind of controller like this?

Suzanne Ciani: No, Sean Canty and Andy Votel. They are amazing; they’re so cool and they are very clever fellows. I loved touring with them.

zZounds: Did they bring out something of your performance that was unexpected, just by the way they perform themselves?

Suzanne Ciani: Everybody who works with technology knows what a cliff if it is. When you’re out doing a tech tour the “on” switch might not work and you’re stressed. In my day, with live electronics, it was like going to the moon. It was like going to the NASA space shuttle lift-off. You had to have doubles of every instrument, and you had to have all this backup, just in case something failed. If there was one glitch in the system, the whole system went down. So, it’s very stressful touring with technology, it’s really exhausting.

What I loved about being with Andy and Sean is that it was the first time I didn’t have to worry about anything. If the plane cargo ruined my Buchla, and it came only half-working, the show was going to go on OK. We had all these different fall back positions. I had never, ever been so relaxed in a performance situation. Contrary to that, this Moogfest I’m solo. I’m going right back to this horrific thing.

zZounds: Do you have nerves about performing at Moogfest?

Suzanne Ciani: The nerves are: “will the equipment work?” Two: “will it be damaged by the airline?” That’s the kind of stuff you worry about. It’s fragile gear and you never know what’s going to happen and maybe it will all be fine. It’s a bit unknown, so therefore it’s stressful. I had techno-breakdowns earlier in life. When you’re completely dependent on technology and that technology is not dependable then you’re in trouble.

zZounds: Do you have confidence now in whatever you’re going to compose and whatever is going to come out of the equipment itself once you get there?

Suzanne Ciani: It’s all about being in the moment. You don’t know what’s going to happen. What I’m supposed to be doing right now is interacting with the machine. There is a lot of information there. You have a patch and it’s complex, but your fingers have to move very quickly, instinctively. So, you have to be aware of what your patch is set up to do, so you know where to jump and where to reach, which you know will do this or that.

You make a set of decisions which is the design of your patch. Where those cables are is fixed. You might move a few during the performance, but the basics, the organization, is committed. Then you’re extemporizing between those parameters. It’s jazz.

zZounds: Since you’re doing all these new performances based on the Buchla, is there something we can look forward to based on your recent electronic performances or explorations?

Suzanne Ciani: Well, my record label has been independent since 1994 and all my fan base is based on my romantic or piano music. I haven’t taken on the notion of releasing my electronic music. I am open with working with other people. I just did a project with a fellow in France and a fellow in Barcelona, etc. I find it a little bit more collaborative for me now. I don’t want to set up a whole new set of electronic releases. My electronic music confuses some of my fans. They get upset.

When Finders Keepers released Lixiviation, I never promoted it at all, because I was afraid. And somebody would say “a new Ciani album is out” and then they’d hate it because it’s electronic. There are two worlds out there that don’t cross ever.

Some fans can absorb all the variables. I had a project I wrote in 2005 in Venice, Italy and it was a romantic album but I haven’t produced it yet. I was hoping to do it this spring, but then I started working for Moog. So, I haven’t done that. I don’t know if I’ll do the album. You know what would be fun?

They did a sound library for the Moog Foundation. MOTU released it. Moog asked me to create some examples. So, I took one of the pieces from Venice and I mocked it up in the library and it was a lot of fun. I got into this idea of doing this album and I don’t know how it would be whether it would acoustic or electronic. I hate using plug-ins but I think it would be something like this because how much I enjoyed it.

Leave a Reply