Let me first start by apologizing. My apologies to Julia Holter, Kelela, and Deerhunter, for not extending the courtesy of detailing how vital their latest works are to this musical year. This same mea culpa of not extending my critique to them, I’d like to extend that as well to the latest works of Neon Indian and Kurt Vile; two dudes who know how to keep on doing, what they’re great at doing in their own unique way. I’d gladly tip my hat to the latest works from Destroyer and Grimes as well. These albums, all albums, with what little clout I have, I’d recommend you dedicate some of your day to discovering on your own. However, today, I’d like to share with you an album that demands more of your time. And in a way, more of your attention.

Visitors from the South

Such are the vagaries of life, that albums like Pierre Barouh’s Le Pollen serve as meaningful reminders to what, the all-encompassing what, we stand to lose when we don’t do some kind of meaningful wandering from our known hemispheres. Born in 1934, in the slums of Paris, Pierre spent his early life in hiding. As a child of Sephardic Jewish parents, persecution drove his waking day. At the time, freedom, the barest of one, the one to move around, was a luxury they ill-afforded. Spending the day hiding in ditches and nights trying to survive on whatever goodwill other peasants provided was their daily routine.

By the time World War II was over, reintroduction into society had come at a cost: Pierre. Barely literate, and struggling mightily to comprehend the educational system he was now introduced to a certain feeling of powerlessness made him feel unattached to a resurgent France. In a France that valued intellectualism and class, he had little of it. Thought of as an imbecile, his family ventured his life was doomed to poverty. Twists of fate deemed it differently. One day, when he was 14 or 15, he experienced something that changed his path.

On that day, he was granted permission by his parents to attend a cycling competition in Paris. Warned not to stay past 9 PM, he heeded their request and came back early. Enamored by the cinema, something he did understand, Pierre snuck into the only film showing that day: Les Visiteurs du Soir by Marcel Carnes. Released in Vichy France during the war, the movie itself was a unique piece of art. Shot in the style of “Poetic Realisme” it mixed less-mannered (some would say fatalistic) ideas of class with much more complex lyrical dialogue, all of it driving at some uncertain certain thing in life. What fascinated and ultimately changed Pierre were these three phrases written by Jacques Prevert and sung in that movie:

“Demons et merveilles, vents et marées, pour moi déjà la mer s’est retirée.”

- Demons and wonders, odds are, that for me the sea has already receded. – Jacques Prévert

DEMONS ET MERVEILLES FROM LES VISITEURS DU SOIR

Its in that song that a whole new world of poetry had opened for him. Poetry that could be romantic, realistic, and deeply moving, in ways that were intrinsically tied to music sharing that same spirit. Its this first, modern era of French Chanson that now concerned him. As he started to inculcate himself in the words of other modern French lyricists like Georges Brassens, Charles Trenet, and Blaise Cendrars, his own spirit started to move into writing and creating music. In doing so, he would obrain the kind of education he never was able to receive before. This then set into motion what would be his greatest realization.

Its realizing that if he wanted to know the world, before it receded from him, he needed to go out there and discover it (demons and wonders, wherever they may be). Making a contract with himself, he pledged to walk the world until he turned 30. Passport in hand, he lived the Bohemian life, hitchhiking his way through 7 or 8 other countries. When he finally reached that age, when his own contract ended, the vagaries of life had led him to make a living not as a musician (as he had hoped), but as a sports writer, then an assistant director in plays.

A Man, and a Woman

Then certain fortunes, little things that set the path on again, like getting bit roles as an actor, transitioned into bigger ones like getting his first record contract based on some existing songs. In spite of getting closer to his original beat, Barouh felt that this certain dream wasn’t what he hoped for. Its path easing a certain restriction he didn’t want to set in. Tied to a contract world where fame, cars, and money were the driving force, felt oppressive at a time when his past availability (to sing, perform, and collaborate with whom he pleased) was readily more tenable when he didn’t have this limitation and could walk when he pleased. In the mid ’60s, a chance meeting with jazz musician Maurice Vander and composer Francis Lai presented him with an option towards a third way through.

You see, a few years earlier, Pierre had gotten the idea of setting his sight to Brazil. Working on a cargo boat sailing from Lisbon, he arrived in Rio hoping to discover the land and its people. What he came back with, was a love for something else: its music. Idealistic, but realistic, he had to head back realizing that he’d lost his chance of meeting some of the musicians whose music he’d only started to fall in love with. However, within a certain amount of time, and a certain amount of chance, fate smiled on him, and he was invited to a dinner party in Paris.

At that party, Samba visionaries Vinicius de Moraes and Baden Powell were in attendance. Hitting it off instantly, Pierre struck up a friendship with them. With time, they would be introduced to other French musicians like Georges Moustaki and Claude Nougaro, all like Pierre, with ideas signaling a change away from the darker hues of traditional Chanson he heard of as teenager. As he travelled more freely back and forth to Brazil, meeting and socializing with other Brazilian musicians, he learned something else. In Brazilian music, the bittersweetness of it all, there was a certain freedom that had yet to be introduced to French audiences.

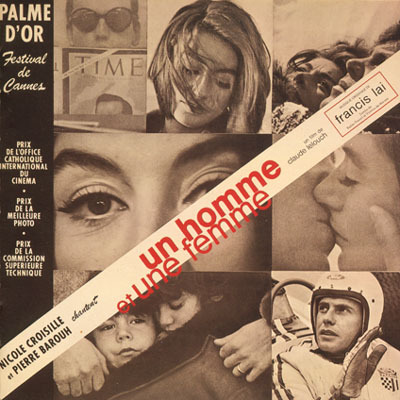

Working with Maurice Vander and Francis Lai, he’d adapt, or explore, a fusion of these two styles and the much more expanded emotional/musical palette they could exhibit. Songs that would later become immensely popular like “Samba Saravah” or “Un Homme et Une Femme” were deemed too different from what was already out there. However, sometime later, filmmaker Claude Lelouch caught wind of these recordings. Interested, for the first time, in setting his films to a soundtrack he struck an interesting proposition to Pierre.

To match his revolutionary filming technique for the film, one that would mix color, black and white, and films of different stock, with scripted realism, he wanted Pierre to play a role as a prominent actor in it. Playing the soundtrack as he filmed, they were instructed to use it as a way to influence their line or improvisations. Separating the line between soundtrack and realism, this film would end on an upward beat as a true-to-life affront to a lot of the unfailingly nihilistic or depressing films coming out in France then. Presenting this France that could be something other than gray, in vivid color, and in tone and fashion, it and the accompanying soundtrack became the massive hit of the year. While Claude and Francis would garner the accolades (be it a Palme D’Or, BAFTAs, or Oscars), Pierre gained something he always wanted: the financial clout to explore more freely.

SCENE FROM UN HOMME ET UNE FEMME (FEAT. PIERRE BAROUH)

Taking advantage of a trip filmmaker Pierre Kast made to Brazil, Mr. Barouh took it as an opportunity to reacquaint himself with musical friends of his in Brazil. In a short bit of time, Pierre Barouh was given by Mr. Kast the allowance to use his film and video/sound crew to document something that was of interest to Pierre. Learning as he went, Pierre started the fruitful task of documenting the rising Bossa Nova scene, and its roots in the existing folk music of Brazil. When he had enough film, he set back into France and released this film, planting the seed for a new kind of world music. The footage now served as an immensely vital piece of musical history. It’s this film and music that would serve to introduce French listeners to other Brazilian styles living alongside the Bossa Nova.

SAMBA SARAVAH (THE FILM) BY PIERRE BAROUH

When he realized that no one saw fit to publish the songs from Un Homme et Une Femme Barouh used his earnings from this film to start his own record label Saravah and use it to set a new course: as the first truly independent French record label. Using money from the massive sales of this soundtrack, he built a recording studio where artists were free to experiment, and in due time, a sizable list of vanguard French musicians.

From a small roster featuring the likes of Brigitte Fontaine, Jacques Higelin, and Francis Lai, he was able to present this vision of Nouveau Chanson, one where influences far from the Western Hemisphere and Europe itself, could easily traffic in the same wavelength as theirs. When you’d see an artist like Brazilian Nana Vasconcelos appear in the catalog, one wouldn’t bat an eye, because such was the accepted mercurial sound of Saravah. Always selling enough to launch and maintain the budding talents of these artists, before they headed elsewhere altogether, Pierre tried to dive his label the authority to remain experimental and free of restrictions.

SARAVAH ARTISTS BRIGITTE FONTAINE AND ARESKI PERFORMING WITH THE ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO

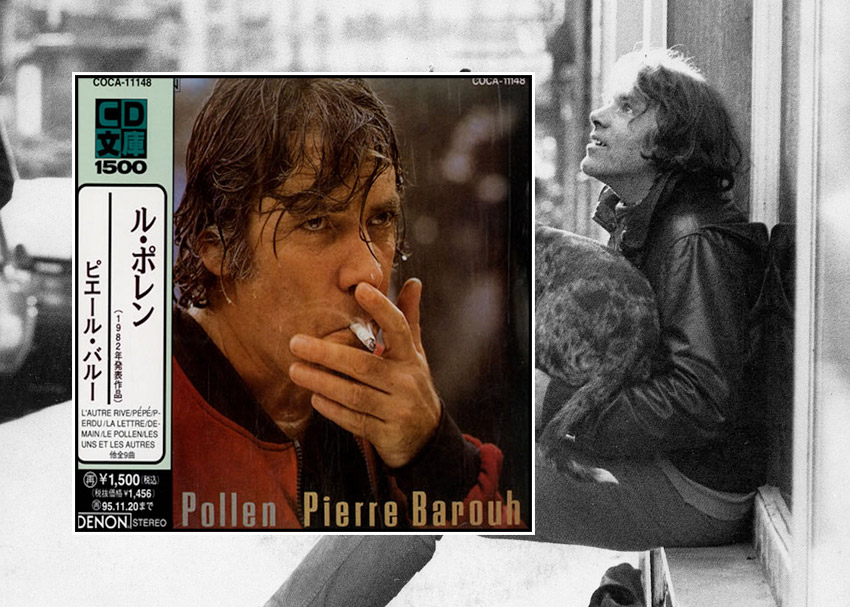

Barouh’s own music remained its own entity. Still finding ways to push his own Brazilian influences in different directions, his initial foray, 1972’s Ca Va Ca Vient featured a sophisticated, studied take on Brazilian styles blended with French mannerisms. He chose to reside much further behind the limelight, letting his explorations remain personal, while his own artists would do the musical envelope pushing. When 1976 rolled around though, Barouh finally attempted to recapture some new kind of progress.

Le Nouvelle Chanson

For Viking Bank he opened up his music for others to reimagine. Drawing from that same stable of artists, Barouh would encourage them to drop in and contribute piecemeal to the grander picture. Updating songs via luxurious arrangements, or dropping intricate, electronic adornments as needed, Pierre produced the album as a blend of what the Saravah sound could stand to be. Songs like “Altitude,” “Viking Bank” or “La Bicyclette” showing giant steps Chanson could place in areas where the style had unique strengths.

Strings that lingered like the densest of air, basses that pumped directly at the heart, pianos that transformed in the ether, and vocals that absorbed all of this headspace, Post-modern and Technopolitan (much like Scott Walker’s work in Nite Flights or Joni Mitchell’s Don Juan’s Reckless Daughters, it was beyond what many people were ready for then. In 1977, the album was released and promptly forgotten by French audiences unsure of what to make of it. In Japan though, it became a underground masterpiece, and Barouh became a musician’s musician.

For all intents and purposes, artists on Pierre’s label were somehow never as popular in France and they were in Japan. Maybe, in that Saravah sound, Japanese artists saw something that spoke to their own attempt to reconcile tradition and modernity through music. It was in the early ’70s that many of these same artists who had grown interested in Yé Yé, Chanson, European Jazz, and Samba, would in turn digest the work of Saravah. So much so that around 1981, Pierre got a fantastical proposition. A Japanese label offered to have him come to Japan and record an album with local musicians. Pierre, never one to shy away from an adventure, took him up on his offer.

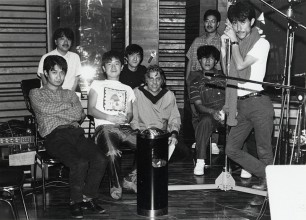

Arriving in Japan, he was surprised to learn that the musicians who offered to work with him weren’t nobodies but Japanese artists at their peak: Ryuichi Sakamoto and Yukihiro Takahashi (both Yellow Magic Orchestra members). Another surprise was how much younger they were than him. Rather than make these artists bend to his sound, Barouh wanted to meet them in balance. It was prime importance for them not to look at his past work with reverence but for him to have something new to offer this generation. As surprised as he was with how well versed and influenced they were by his previous work, he didn’t want them to feel hindered by it. Armed with new songs and an open mind, he wanted them to attempt to blend all this tradition into some new other.

What transpires in the album, and in the spirit of the music, was this special place all these artists were able to discover. A truly special time for music can be found here. Joining them would be others like David Sylvian and Mariah mastermind Yasuaki Shimizu, and members from Moonriders, all injecting experimental pop ideas into another world a bit more ready for this even further Hyper-Cosmopolitan vision of Chanson music. Songs like the Shimizu-composed “Parenthèse” feature bits of otherworldly torch song atmosphere, where traditional instruments and arrangements mix seamlessly with untethered electronics and sequences. In the towering highlights of the album, the dramatically updated “Perdu” and “Le Pollen”, you hear all the roots of these musicians, found in Ambient, Dub, Techno Kayo, R&B, Chanson, Japanese Folk and many more styles, filtered through an open mindset. In these sessions, this is where these same musicians would be able to stitch those endings together with the finest of thread and create this whole new fabric that can be its own source of inspiration.

It’s albums like these that are even more vital in this era when the demons of the world try to make us build borders at the water’s edge and separate us from the vastly larger, and more fulfilling wonders waiting for us.

“Le Pollen” itself reveals the most important source for the why. It’s this idea, not of acquiring culture for superficial reasons, but of acquiring it to advance personal communication. United through music, all these gifted musicians were able to have a dialog that goes beyond mere language and vocabulary. Beyond the timeless music, these words still stick with me from “Le Pollen:”

“Aujourd’hui, je suis ce que je suis

Nous sommes qui nous sommes

Et tout ca, c’est la somme

Du pollen dont on s’est nourri”Pierre: “David, can you translate that for Yukihiro?”

David: “Yes, I think so.”

David: “Today, I am who I am

We are who we are

And everything is, as it is

The pollen which we feed on”Pierre: “Yukihiro, can you say that in Japanese?”

David: “Today, I am who I am”

Yukihiro: “高橋幸宏”

David: “We are, who we are”

Yukihiro: “今日、僕は僕”

David: “And everything is, as it is”

Yukihiro: “僕達は僕達”

David: “The pollen which we feed on”

Yukihiro: “そして、そしてね、全ては僕達を培ってきた花粉”

- a conversation between Pierre, David, and Yukihiro as heard on “Le Pollen”

As impressive as the albums are I referenced in my first paragraph, history has been kind to deliver them in a time when someone will proselytize for them and leave some record of their importance. With what little clout I have, though, my musical wandering has taken me far enough to finally understand how deeply important it is to not forget, and if possible document somewhere, some of the extremely vital musical vocabulary that won’t be afforded this same luxury. At the end of the day I may just be a peasant, but here, here is my bit of grain. And here, right here’s a bit of territory we can dig in.

Find pierre barouh and more from the saravah label here:

Saravah Record Label Official Website

Leave a Reply